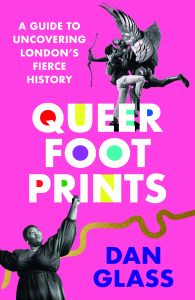

We speak to Dan Glass about his new book, Queer Footprints: A Guide to Uncovering London’s Fierce History, which explores London’s queer history through mapped walking tours, informed by archival research and interviews with activists and volunteers involved in LGBTQIA+ movements over the decades.

LSE Library organised a Picadilly walking tour and panel event on Friday 9 June 2023 to mark the book’s launch which featured a display of materials from LSE’s Hall-Carpenter Archives and panellists from the UK branch of the Gay Liberation Front (GLF), formed at LSE in 1970.

Dan Glass has several upcoming events as part of his book tour in London, Dublin, Berlin and Brussels. Find out more about how to attend through the Queer Footprints LinkTree.

Q: In 2017 you launched Queer Tours of London – A Mince Through Time, and Queer Footprints: A Guide to Uncovering London’s Fierce History (2023) seems to build from that. What was the impetus was for both projects?

Q: In 2017 you launched Queer Tours of London – A Mince Through Time, and Queer Footprints: A Guide to Uncovering London’s Fierce History (2023) seems to build from that. What was the impetus was for both projects?

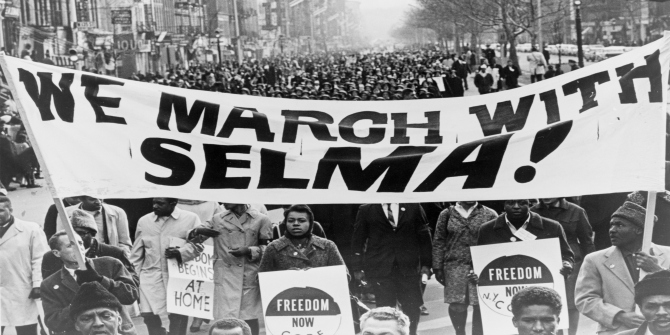

A book that is inspiring and useful for me is Angela Davis’s Freedom Is a Constant Struggle. She articulates the impetus for me when she says, “there’s grave collective psychic damage that is a consequence of not being acknowledged within the context of one’s ancestry.” She’s looking at it from a Black anti-racist perspective, but there are parallels for queer consciousness, because of Section 28 [legislation in place from 1988 to 2003 banning local authorities and schools from promoting homosexuality] and other forms of institutional homophobia, and the [resulting] higher rates of anxiety, depression and suicide and in the LGBTQIA+ community.

When I started connecting with my queer ancestry, I couldn’t get enough, because I see the power of owning our roots and celebrating the ancestors who fought for our existence today and all the incredible nooks and crannies we’ve been denied knowledge of, the revolutionary movements and extraordinary people who’ve set up the pubs and spaces that have made us who we are. Queer Tours of London started in the smoking area of the Joiner’s Arms club on Hackney Road when we found out it was going to be shut, and this was on top of the closure of Madame Jojo’s, the George and Dragon and the Black Cap and lots of spaces [58 percent of queer venues in London closed between 2006 and 2016] and we weren’t having it anymore.

I wanted to do Queer Footprints partly because the pandemic happened: we couldn’t do Queer Tours. I really wanted to challenge myself by writing it and expand Queer Tours into a written format. I was also aware that a lot of the people who I’m really inspired by are getting old and I wanted to record their stories.

The incredible nooks and crannies we’ve been denied knowledge of, the revolutionary movements and extraordinary people who’ve set up the pubs and spaces that have made us who we are.

Q: What approach did you take to doing the research and curating it into a book?

I love an archive and I spent so much time in the Hall-Carpenter Archive, in the Bishopsgate Institute, in London Metropolitan Archives, and it was just calling out for it to be made into a book. The book is about sexual-spatial geography: who owns this city? There are so many incredible examples of how we have emerged and sometimes thrived amongst the cracks of the city, whether that’s cruising or creating underground meeting spaces. It was a combination of 200 interviews, and through my activism I was already connected with a lot of the communities – I’ve been active in Aids Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP), in the GLF, in the Sexual Avengers and various other movements. The difficult part was cutting it down because I ended up with 2000 case studies of queer protest or parties or revolutionary happenings.

There was also reading lots of newspapers, reading other books like Queer London, Matt Houlbrook’s book which [covers] mainly 1918 to 1957, the era just before the one I write about. And also just keeping my ear open for other things – it was a process of active engagement.

The book is about sexual-spatial geography: who owns this city?

Q: The book contains testimonies from LGBTQIA+ activists, business owners, volunteers and artists who speak to the histories (and herstories) you trace across London. Why did you feel it was important to include their voices in Queer Footprints?

My main training is with Training for Transformation, an educational project born out of the marriage of the Black Consciousness movement in apartheid South Africa and Paulo Freire’s work around the Pedagogy of the Oppressed [and popular education]. Popular education is the opposite of “banking education” (where we’re seen as empty vessels and education needs to be deposited into our heads) and says instead that we are authors of our own reality. So, for me, having human-centred stories is the spark that lights the movement.

History is often told by those who have the luxury to write it, and this is why I say “herstory,” because I wanted it to be written from a feminist perspective. One of the examples is Carla Toney’s story in the Trafalgar Square chapter, the first woman and lesbian to make a speech at the first GLF youth demonstration in 1971. And her story had never been written down in a book.

Q: Throughout the book you highlight solidarity between different movements and the intersectional nature of struggle, such as challenging racism faced by queer people of colour or the solidarity of Lesbians and Gays Support the Miners (LGSM). How did these other struggles impact the movement for LGBTQIA+ equality?

An intersectional approach is not just vital on a moral level, it’s vital on a political level. The powers that be thrive on separating us and not letting us connect. We’re all impacted by the same dominator culture of patriarchal, sexist, homophobic, racist, ableist violence – we’re all affected within that framework, so we all have to work together on the ground. It’s deeply powerful – lesbians and gays supporting the miners is a classic example of the strength of movements coming together, which helps people humanise each other as well as being deeply politically effective.

Q: In the book’s introduction you stress the importance of movement, walking and taking up the space, of engaging with history rather than just reading about it. Is that something you want readers to take from the book?

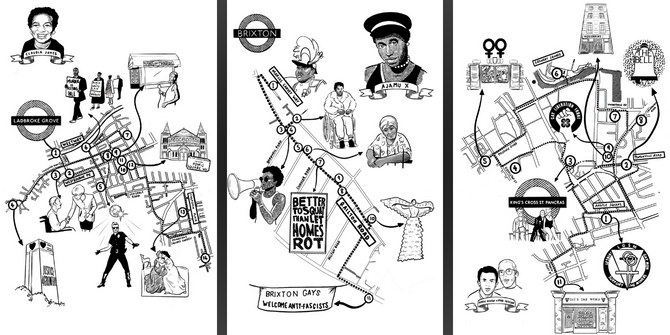

Definitely. It’s a pilgrimage to sacred spaces which have made us who we are, whether we’re talking about underground queer dance halls or the shebeens in Brixton or Ladbroke Grove, or places of defiance like early pride protests as well places of LGBTQIA+ plus hate crime attacks like in Tower Hamlets cemetery, police raids in the Caravan Club or [the bombing in] the Admiral Duncan.

Visibility is everything when it comes to Pride, and that was always one of the key essences of the GLF: come out. Being visible is even more important when we’re facing the rise of LGBTQI – and all – hate crime attacks, racism and fascism emboldened by the rhetoric of this government and Brexit. So, [the walking tours are] a very practical way to reclaim our streets, reclaim our spaces, and [build] connection.

The walking tours are a very practical way to reclaim our streets, reclaim our spaces, and build connection.

Q: What do you believe is the value of documenting and celebrating past struggles to movements now?

One phrase which sticks with me is the freedom struggle mantra “a luta continua”, Portuguese for “the struggle continues,” that’s much used across lots of different movements – trade union movements, anti-racist movements, healthcare movements. It’s a recognition that we’re part of this powerful movement of people all striving for a better world.

My main epiphany throughout writing the book is that our community is incredible. We’ve got all the tools that we need. When it comes to international movements, it’s all about continuing to share the things that help us win, and it is about perseverance and seeing this in the long term. All the tyrannical homophobic legislation is inspired by each other, because of the British Empire, because of Section 28: the “gay propaganda” law in Russia, the Polish “LGBT-free Zones.” What’s going on in Uganda at the moment is practically a carbon copy of the Henry VIII’s Buggery Act in 1533. So just as they are inspired by each other, we have to be inspired by each other to help overturn [the legislation].

I would really like to do Queer Footprints collaborations in countries where it’s more at the sharp end of the knife because if we’re looking at equalising liberation across the world, then we need to do more work with [those] communities. To be able to do this in Russia, for example, or Palestine or in Uganda with my friends there who are challenging the latest tyranny.

Q: The book takes account of discrimination and pays tribute to victims of oppression, like those who died during the AIDS crisis. At the same time, the book is full of joy and vibrancy captured in anecdotes from queer bars, club nights and events in London over the decades. How did you strike this balance?

When you see how bad things can go, when you go to the Admiral Duncan, for example, you also have the other end of how beautiful things can be. To be able to see both ends of the spectrum, it shows the power of humanity to be resilient, to go through painful things and to come out the other side stronger and more connected. For lots of people in the book (the ones at the top of my head are Mark Ashton and Mike Jackson from LGSM) wit, satire and self-deprecation have always been a tool for survivors.

One thing I specifically tried to do in this book is to be optimistic. Angela Davis talks about optimism as a radical act: “You have to act as if it were possible to radically transform the world. And you have to do it all the time.” Also, Paulo Freire’s book Pedagogy of Hope says that we continually have to sculpt hope in our lives and our movements. Not in a false way of “let’s all link arms and give peace a chance.” No: we have to look at the structures in society and build structurally in response. That’s one thing which helped me strike [the balance]: movements which are hopeful, and which have created active change.

Note: This interview gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science. The interview was conducted by Anna D’Alton, Managing Editor of the LSE Review of Books blog.

Banner Image: Illustrations of the Queer Footprints walking tour routes by Mark Glasgow ©, reproduced with permission.