by Raymond Hinnebusch, University of St Andrews

This memo was prepared for ‘The Arab Thermidor: The Resurgence of the Security State’ workshop held at LSE on 10 October 2014 in collaboration with POMEPS.

What explains the failure of the Arab Uprising to lead, as its protagonists expected, to democratization? Neither democratization theory (DT) or post-democracy (PDT) approaches, such as authoritarian upgrading, got the Arab Uprising right: Several authoritarian rulers were removed but rather than democracy, the dominant outcome has been some variant of civil war or authoritarian restoration. Historical sociology (HS) has key advantages in understanding this outcome. It can subsume the contributions of DT regarding the forces pushing for democratization and the insights of PDT on how these have been managed, while overcoming their tendency to teleology and dichotomization and bringing in depth from history and political economy.

Path Dependency over Teleology: The Historical Construction of Authority

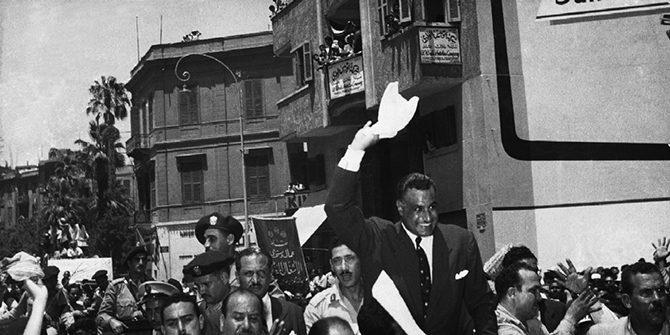

Instead of teleological assumptions of a universal democratic end point of development, HS sees post-uprising outcomes as products of “path dependency,” – historically “successful” practices and institutions get reproduced and adapted to new conditions. Weber, building on Ibn Khaldun, identified the historically dominant “successful” paths to authority creation in the Middle East and North Africa and certain hybrids of his authority types have been typical of contemporary times, notably the mix of charismatic and bureaucratic authority by which populist authoritarian regimes were founded (with Gamal Abdel Nasser’s Egypt the prototype) and the mixes of patrimonial and bureaucratic authority (neo-patrimonialism) toward which they evolved in their “post-populist” phase. Each of these “solutions” were attempts to “fix” flaws in previous regimes, but also generated new vulnerabilities, driving further adaptation.

Variations in these historic state building pathways can be expected to matter for the trajectories of the Arab Uprising. All the republics were neo-patrimonial but the differing balance between their patrimonial and bureaucratic components shaped the short-term outcomes of the Uprising. Where bureaucratic institutions had a degree of autonomy from the leader, as in Tunisia and Egypt, state elites could sacrifice him to save themselves without imperiling the regime and relatively quickly reconstitute their dominance;[1] otherwise, presidents could not be jettisoned without imperiling the ruling coalition and the stability of the state. The balance among the bureaucratic pillars also mattered: Where, as is usual in MENA, the military was the main state pillar, democratization was less likely than a hybrid regime; Tunisia was the exception, where the trade unions, as the main partner of the nationalist independence party in constituting the state, pre-empted the military’s role.

Path dependency also allows us to anticipate the likely medium-term outcomes of the uprising: Weber’s authority practices, the products of learning over long historical periods, will be deployed in efforts to reconstitute regimes – around some combination of charismatic, patrimonial, and bureaucratic authority. None of these proven authority building formulae are democratic, per se, although only patrimonial authority is explicitly non-democratic, while charismatic authority has an element of mass mobilization (with ideological political parties a modern form of charismatic authority) and bureaucracy is built on the principles of merit recruitment, equality before the law, and limits on the legitimate authority of office holders. As these versions of authority constrain patrimonial authority, democratic possibilities increase.

>> read the full memo on the Pomeps Website

Other available memos in the series

‘The Authoritarian Impulse vs. the Democratic Imperative: Political Learning as a Precondition for Sustainable Development in the Maghreb’, John P. Entelis, Fordham University

‘Elite Fragmentation and Securitization in Bahrain’, by Toby Matthiesen, University of Cambridge

‘Militaries, Civilians and the Crisis of the Arab State’, by Yezid Sayigh, Carnegie Middle East Center

‘Arab Transitions and the Old Elite’, by Ellis Goldberg, University of Washington

‘Explaining Democratic Divergence: Why Tunisia has Succeeded and Egypt has Failed’, Eva Bellin, Brandeis University

‘Is Libya a Proxy War?’, Frederic Wehrey, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

‘Fiscal Politics of Enduring Authoritarianism’, Pete W. Moore, Case Western Reserve University

‘The Role of Militaries in the Arab Thermidor’, Robert Springborg, Sciences Po

‘Mass Politics and the Future of Authoritarian Governance in the Arab World’, Steven Heydemann, United States Institute of Peace

‘Security Dilemmas and the ‘Security State’ Question in Jordan’, Curtis R. Ryan, Appalachian State University

‘Authoritarian Populism and the Rise of the Security State in Iran’, Ali Ansari, University of St Andrews

‘The Arab Thermidor’, Marc Lynch, George Washington University