by Pete W. Moore, Case Western Reserve University

This memo was prepared for ‘The Arab Thermidor: The Resurgence of the Security State’ workshop held at LSE on 10 October 2014 in collaboration with POMEPS.

“In many areas of the Middle East and Latin America, revolutionary pressure continues to build up…The problem which has to be solved, and to which no one has yet found a satisfactory answer, is how to bring about change in the balance of power which is needed to avert revolutions without having a revolution.”

-Nicholas Kaldor, “Will Underdeveloped Countries Learn to Tax?” 1963

Fiscal politics is the study of how states and societies extract and distribute resources, and the effect of these policies. This is an interdisciplinary literature in which social scientists and historians from different analytical backgrounds have long recognized the importance of taxation and fiscal regimes for state building, democracy, and rebellion. In the study of the Arab world, a truncated form of the study of fiscal politics, rentier state theory, has dominated. I will outline a different fiscal politics approach, one that focuses on the long-term fiscal crisis of the less resource rich Arab states and how those regimes have responded. My simple claim is that political authoritarianism in the Arab world has come to accommodate strategies of fiscal weakness. I cannot quite argue one caused the other, and at this point I am more interested in tracing the effects. My understanding of fiscal crisis draws on an older literature, such as James O’Connor’s The Fiscal Crisis of the State, as well as the late Samer Soliman’s 2011 work on fiscal crisis and political change in Egypt.

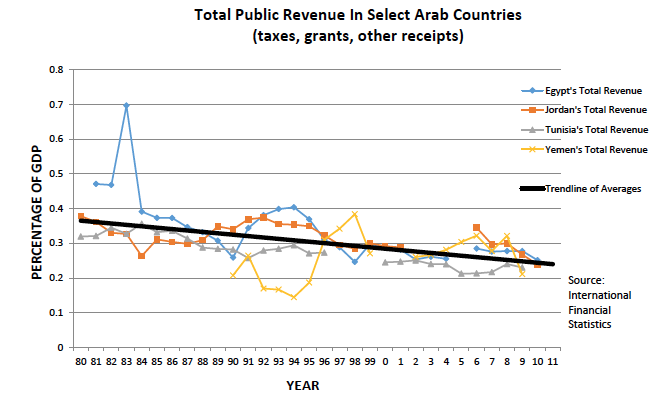

Despite decades of economic growth and expansion since the 1970s, Arab states have witnessed steady declines in levels of total public revenue. At the same time, the socio-economic expectations of coalition supporters compelled regimes (to attempt) to continue meeting those demands. This fiscal dilemma and vulnerability to periodic economic crises provides one way to understand regional bouts of rebellion starting in the late 1970s and culminating in 2011. This perspective also reveals political economy structures of authoritarianism, which are likely to deepen after 2011. In the rest of this essay and relying primarily on evidence from Jordan and Egypt, I focus on the dilemmas fiscal weakness has spawned: greater labor market insecurity, privatization of urban infrastructure, and more regressive taxation.

>> read the full memo on the Pomeps Website

Other available memos in the series

‘The Authoritarian Impulse vs. the Democratic Imperative: Political Learning as a Precondition for Sustainable Development in the Maghreb’, John P. Entelis, Fordham University

‘Elite Fragmentation and Securitization in Bahrain’, by Toby Matthiesen, University of Cambridge

‘Militaries, Civilians and the Crisis of the Arab State’, by Yezid Sayigh, Carnegie Middle East Center

‘Arab Transitions and the Old Elite’, by Ellis Goldberg, University of Washington

‘Explaining Democratic Divergence: Why Tunisia has Succeeded and Egypt has Failed’, Eva Bellin, Brandeis University

‘Is Libya a Proxy War?’, Frederic Wehrey, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

‘The Role of Militaries in the Arab Thermidor’, Robert Springborg, Sciences Po

‘Mass Politics and the Future of Authoritarian Governance in the Arab World’, Steven Heydemann, United States Institute of Peace

‘Security Dilemmas and the ‘Security State’ Question in Jordan’, Curtis R. Ryan, Appalachian State University

‘Authoritarian Populism and the Rise of the Security State in Iran’, Ali Ansari, University of St Andrews

‘A Historical Sociology Approach to Authoritarian Resilience in Post-Arab Uprising MENA’, Raymond Hinnebusch, University of St Andrews

‘The Arab Thermidor’, Marc Lynch, George Washington University