by Pejman Abdolmohammadi

This memo was presented at a workshop organised by the LSE Middle East Centre on ‘Mapping GCC Foreign Policy: Resources, Recipients and Regional Effects‘ on 7 October 2015.

Following the Iranian revolution of 1979 and the subsequent establishment of an Islamic Republic, the geopolitical role of Iran in the region has changed radically. From an ideological point of view, the new Iranian state, centred on Shiʿa Islam, began to develop its international relations on the basis of a new political identity, characterised by two key elements: the unity of the Shiʿa Islamic forces and anti-imperialism – ideas that were both spread by the leader of the revolution, the Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini.

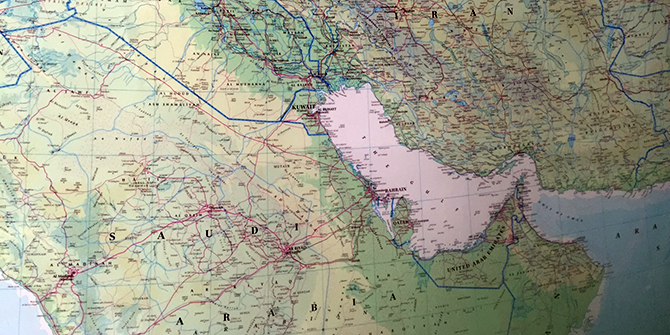

It was along this line of thought that Tehran reformulated its alliances during the 80s and 90s. The result of this new policy became evident through the gradual establishment of a Shiʿa centre of power in the Middle East, then known as the ‘Shiʿa triangle’. A political network composed of Tehran, of the paramilitary group Hezbollah in Southern Lebanon (established in 1982 also thanks to the financial and logistical support of the Islamic Republic), the Alawite faction, in power in Syria and led by the Assad family, and from the Shiʿa part of Iraq, concentrated in the holy cities of Najaf, Karbala and Sameera. This triangle has gradually increased its political power during the late 90s and the first decade of the 21st Century. The fall of Saddam Hussein, following the intervention of the United States in 2003, strengthened this Shiʿa coalition. This has allowed Iran to increase its influence in Iraq and to play a key role in the formation of the successive Iraqi governments, led by the Shiʿa majority. In particular, the former Prime Minister of Iraq, Nouri al-Maliki, was politically connected with Tehran.

It could be said that from 2003 to 2010, before the start of the so-called Arab spring and the Syrian crisis, Tehran, as the leader of the ‘Shiʿa triangle’, played a fundamental role in the balance of power of the Middle East. In fact, the area referred as the ‘Shiʿa triangle’ was not limited to the four countries mentioned above, but was committed to expand its influence everywhere that Shiism had political or cultural roots. An example worth noting is that of Yemen. Here the Shiʿa (even though Zaydis and not Twelver) continue to oppose to the pro-Sunni factions, supported both by Saudi Arabia and Turkey. Also Afghanistan, in particular the city of Herat, has been subjected to the influence of Iranian Shiism. The same dynamics can be observed in the GCC countries, especially in Bahrain and Kuwait, which both have an important Shiʿa presence, posing as a potential threat to the Sunni families currently in power.

Clearly this political strategy of exporting Shiʿa ideology in the Islamic world has provoked a strong reaction on the part of GCC States, particularly Saudi Arabia, which represents the orthodox Sunni group in the region. In other words, 1979 saw the beginning of a cold war between Riyadh and Tehran that continues to this day.

The weakening of Assad caused by the uprising in Syria, the fall of the pro-Iranian government of al-Maliki in Baghdad, the strengthening of the Kurdish component in the region and the birth of the pro-Sunni armed group ISIS in part of Iraq and Syria at the borders with Iran, have all deeply affected the political stability of the Shiʿa front, also decreasing the power of the Islamic Republic in the region. In fact Tehran is, on the one hand, subjected to Western pressure on the thorny nuclear issue and, on the other hand, it is losing the pieces of its “Shiʿa triangle”.

However the recent ratification of the so called ‘Iran deal’,on the nuclear issue, between Tehran and the ‘5+1’ group, on one hand, and the new dialogue among Rohani’s government and Obama’s administration, has been strengthening the role of Tehran in the region, provoking the disappointment of its main competitors such as Saudi Arabia, Israel, Qatar and Turkey. Due to this, the Islamic Republic has to face at least two strategic choices: maintaining the status quo, continuing to invest its forces in the Shiʿa triangle, so keeping unaltered its support for Assad, Hezbollah, the Shiʿa Iraqi front and its influence in Yemen, thus consequently carrying on the cold war against Riyadh and increasing consequently its tension with the GCC countries. Or it can choose to strategically reposition itself and to decrease its support to the Shiʿa components in the region. The first option would lead to a possible conflict between Iran and Saudi Arabia which might seriously damage the Middle Eastern security.

The second option would open a new phase of Tehran’s foreign policy, marked by a more pragmatic approach that would allow Iran to distance itself from the Shiʿa triangle and diminish the threat towards its main regional competitors. For the GCC states Iran’s new position could be seen as a strategic and economic opportunity, favouring new bilateral business and commercial ties with Tehran. Oman, Qatar and Kuwait are perhaps the most probable to exploiting this new opening of Iran. Despite Iran’s more pragmatic approach, relations with Saudi will remain vulnerable, as the two countries are natural competitors.The competitions stems firstly from their geopolitical collocations and hegemonic ambitions in the Persian Gulf; secondly through their symbolical and ideological representations – Saudi Arabia representing the Sunni orthodox and Iran representing the Shiʿa imamites, as well as the two countries epitomising the Arab-Persian symbolic/cultural conflict, and thirdly because both countries are competitors in the energy market.

Relations between Iran and GCC countries, particularly Saudi Arabia, remain a very important factor for the stabilisation of the Middle East. The real threat for the security of the region is not, according to this commentary, the Iran-Israel tension, but the one between Tehran and Riyadh. Therefore, focusing on more pragmatic and constructivist policies to improve the relations between Iran and GCC countries might be important for diminishing tensions and to avoid possible new conflicts in the region.

Pejman Abdolmohammadi is Visiting Fellow at the LSE Middle East Centre. He is also Lecturer of Political Science and Middle Eastern Studies at the American University ‘John Cabot’ in Rome.

Other memos presented at the workshop

- Suliman Al Atiqi, ‘GCC Foreign Policy Projections in the Palestinian-Israeli Conflict: A Comparative Analysis of Saudi Arabia & Qatar’

- Will Bartlett, James Ker-Lindsay, Kristian Alexander and Tena Prelec, ‘UAE Policies towards the Western Balkans: Investment Motives and Impacts’

- Karen Young, ‘The New Politics of Gulf Arab State Foreign Aid and Investment: Evidence from the UAE Intervention in Egypt’

- Courtney Freer, ‘Ikhwan Ascendant? Assessing the Influence of Domestic Islamist Sentiment on Qatari Foreign Policy’

- Christian Henderson, ‘The UAE’s Nexus State: Logistics, Transport and Foreign Policy’