by Rasmus Alenius Boserup

This article is part of a 7-part series assessing the prospects and challenges for the study of North Africa in the wake of the Arab Spring.

Introduction

When revolutionary mass mobilisation swept across North Africa in late 2010 and early 2011, Algerian authorities were arguably better prepared than most of their neighbours: for more than a decade, urban youth protesters had regularly mobilised spontaneously across the country calling for government action on a host of socio-economic strains including lacking housing facilities, cuts in water and electricity delivery, decaying and dangerous infrastructure, and so on. Algerian authorities also had a comparably easier job than their neighbours: in contrast to the Tunisian and Egyptian protesters, who gained momentum as their demands grew tougher, Algerian protesters abstained from pushing for systemic change. Instead Algerian protesters asked for the regime to ‘share’ revenues from hydrocarbon exportation more fairly and withdrew shortly after president Bouteflika made a public pledge to carry out political reform and create economic incentives for the youth. Hence by mid-February 2011 when Tunisia and Egypt had already toppled presidents and Libyan protesters were gathering momentum in Benghazi, Algerian protests faded away.

Retrospectively, protests and uprisings changed little in the domestic political scene in Algeria in 2011. But the rapid transformations of the domestic order in neighbouring countries would prompt experts, scholars and policy makers to raise a series of overdue questions about the nature of governance and the composition of society in Algeria: Who governs? What are their relations to society? How are state expenditures financed? What factors and which actors are underpinning the regime – and are there imminent domestic threats to the existing political order?

A changing domestic order

From 2013 through 2015, I had the opportunity – together with professor Luis Martinez of Sciences Po, Paris – to run a small research project that addressed some of these questions by inviting young as well as established scholars on Algeria to take part in a series of workshops and conferences held in Algeria, France and Denmark. Our concerted efforts, of which the most prominent contributions were published last year, revealed that Algeria had changed considerably since the civil war in the 1990s. Although there were of course continuities, the contributions suggested that the image of an apolitical, traumatised, and endemically violent society governed by an opaque and brutally repressive regime was quite obsolete. Instead, the image of Algerian society that emerged from our studies was one that slowly developed into something far more complex.

For instance, Luis Martinez showed in his study that behind the stereotypical image of an Arab authoritarian regime, the Algerian hybrid structure had its own specific way of operating. Indeed, the opaque nature that had characterised the political system since independence was giving way to the emergence of an increasingly transparent one where actors were publicly known and visible. This visibility, Martinez demonstrated, revealed a series of governance working mechanisms that were more complex that what had been proposed in the totalising metaphors about the Algerian ‘cartel’, ‘clan’ or ‘mafia’ that experts had made use of since the civil war.

Another example was Ed McAlister’s study, which challenged the stereotype of an ‘apolitical’ urban youth population: McAlister demonstrated that identity politics had developed rapidly in Algeria’s urban centres where new youth segments with faint memories of the civil war in the 1990s were quietly challenging the micro-mechanisms of governance and social control utilised by ikhwanis, salafists and former war of independence mujahids alike.

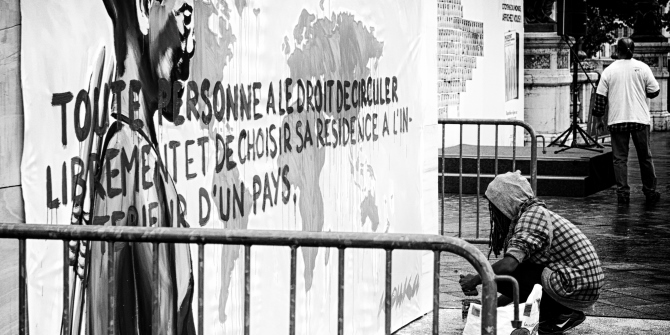

Similarly, my own study showed that protestors in Algeria, in spite of their hyperactivity, were seeking to preserve a status quo rather than transform it. Protests in Algeria generally followed the pattern observed in early 2011: they emerged in response to government failures to deliver on promises, and they dissipated once the government relented. In Bouteflika’s Algeria, I suggested, street protests had not only replaced the violent form of contention known during the civil war in the 1990s, but had also come to served as a mediating mechanism between regime and society on a wide number of socio-economic issues – thereby replacing failing formal political institutions like local councils, parliament and civil society organisations.

While the Arab uprising as such changed little in the domestic scene in Algeria, it emphasised the need for scholars, experts and policy-makers to reconsider long-held assumptions about the country and its domestic power relations.

New regional orientation

It is not just domestic politics that has come under new scrutiny in the wake of the Arab uprisings. Recently scholars, experts and policy-makers have also taken increased interest in the country’s foreign and security policies and in particular its policies towards its southern neighbouring regions, the Sahel. Also in this case, the immediate triggers behind the renewed interest originated from processes happening outside Algeria. In 2013, Libya and northern Mali were both on the brink of state collapse. Each country had been, in spite of opposition from Algeria, subject to international military interventions led by France. Both countries were failing to re-establish central authority. In response to increasingly bold activities by jihadist networks operating out of Libya and northern Mali, and in accordance with the wishes of the international community, the Algerian authorities from mid-2013 began to fortify their southern and eastern borders, transferring control of these portfolios from the intelligence apparatuses to the military.

The shift itself signified a possible reorientation of Algeria’s security and foreign policy that could also have implications for the country’s role in regional power politics. Indeed, while scholars have for decades treated Algeria as a key player in either the Maghreb or the Mediterranean, the partial state collapses in Libya and Mali in the wake of the Arab Uprisings are today forcing Algerian policy-makers to invest considerable resources in the Sahel. As Luis Martinez and I have suggested recently, the unintended consequence of this turn may indeed signify a dawning security overlay by Algeria and its North African competitor – Morocco – in the Sahel region.

Conclusion

The irony of the impact that the Arab uprising has left on the scholarship and expertise dealing with Algeria is that little of this originated from within Algeria itself. Hailed as an island of stability in the unstable North Africa and Sahel region, Algeria has since 2011 changed less than its neighbours, which experienced revolutionary mass protests, complicated and (for some) failed transitions away from autocracy, or state collapse. Intrigued by the transformations outside of Algeria, scholars have, however, in the period after the uprisings discovered a number of deeper changes that have been underway over the past two decades since the civil war, both in the country’s domestic order and in its foreign and security policies.

Rasmus Alenius Boserup is an expert on current Arab affairs. His research focuses on contentious politics and authoritarianism in the Arab World. His key specialization is society, politics, and history in Egypt and Algeria. He tweets at @rasbos

Rasmus Alenius Boserup is an expert on current Arab affairs. His research focuses on contentious politics and authoritarianism in the Arab World. His key specialization is society, politics, and history in Egypt and Algeria. He tweets at @rasbos

In this series:

- The Arab Spring and the Academy: Studying North Africa in the Wake of the Protest by Jonathan Hill

- An Uprising in the Social Sciences? The Study of Middle East Politics in Transformation by Florian Kohstall

- Studying Libya today: Exploring the past to understand the present and shape future research agendas by Anna Baldinetti

- The Politics-Security Nexus in Post-Revolutionary Tunisia by Francesco Milan

- Revisiting the Cultural Field in Morocco and Tunisia after the ‘Arab Spring’ by Cristina Moreno Almeida

- Refugees and ‘Host Communities’ Facing Gender-Based Violence around Mbera Camp, Mauritania by Olga Martín González