by Malu Halasa

When the doyenne of Middle East criticism miriam cooke went to Syria in the mid-1990s looking for women’s writing against the regime, she found prison memoirs and plays critical of Hafez Assad, written by men. When I went to Syria for my book with Rana Salam about the country’s sexy lingerie culture in 2006, we found only one female designer who fashioned a bra and mini-skirt out of burlap. There seemed to be a disconnect between some women and their bodies and some women and the larger body politic. Now I believe I had been looking in the wrong places. In a totalitarian regime where the government’s myriad secret services maintain several prisons for the tortured and disappeared in every Syrian city, resistance and self-knowledge are not on public display; these are cultivated inside hearts, minds, homes, schools and universities.

Fast forward to 2011. The mass demonstrations of Syria’s failed Arab Spring or Awakening not only exposed the fault-lines of Syrian society, it revealed people’s aspirations. It also, as Rana Kabbani explained to me, liberated language and creativity. A generation across the region was freed from the confines of proper Arabic and state-approved culture.

It also made visible women activists working to change the country before 2011 and after. Some, like human rights lawyer Razan Zaitouneh and activist and former detainee Samira Khalil, ran the Violations Documentation Center. In December 2013 they were kidnapped in Douma, along with their male colleagues, allegedly by Jaysh al-Islam. The Douma Four remain missing until today.

Others like Yara Badr and her colleagues at the Syrian Center for Media and Free Expression were jailed by the regime. Now in Berlin, Badr and her husband Mazin Darwish are using the German courts to sue the Syrian government for its torture and murder of prisoners – one of the few initiatives attempting to charge Assad regime officials with war crimes. Writer Samar Yazbek took her prize money from English PEN and seeded Women Now for Development, a civil society organisation running centres in Eastern Ghouta and Idlib against all odds.

In the seven-year-long conflict Syrian women too often appear as victims. The UN Population Fund’s Syrian Voices 2018 report features first person testimony of forced marriage of young girls, gender-based violence against women by male relatives, the victimisation of widows alongside the story that made British headlines in March 2018: Syrian women, seeking humanitarian aid, harassed for sex.

Last year human rights lawyer and MENA director at the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom Laila Alodaat was chilling in her assessment: women are not in positions of power in Syria’s Local Coordinating Committees in opposition-controlled areas. They do not work in the provision and distribution of humanitarian aid, which means they will starve before men.

Alodaat moderated Civil Society and Communities Session for Chatham House’s ‘Demystifying the Syrian Conflict’ conference, which included Women Now for Development’s executive director Maria Al Abdeh. She said 65 women activists from Women Now remain trapped underground during, at the time of writing, the ongoing siege of Eastern Ghouta. Before the current violence 150 civil society organisations – the highest number in the country – worked on assistance, reporting, child protection, emergency response and first aid for a civilian population of 400,000. Earlier that day one of the shelters there sent a request to Women Now asking how help a woman giving birth.

The main role of Women Now, Al Abdeh explained, is to be the voice of civilians, express their needs and respond to them.

Instead international donors demand that a population reeling from famine, bombardment and minimal healthcare initiate ‘peace-building projects’ – an open two-week call that was issued five months ago. When civilians were understandably unable to write detailed proposals, grants went to larger aid organisations, which have failed miserably in the Syrian humanitarian relief effort.

Badael is a Syrian NGO that works with groups in the country on reducing violence. Its director Oula Ramadan said the foundation recently withdrew from the peace negotiations’ Civil Society Room because of the lack of an agenda and insufficient time given for liaising with members on the ground.

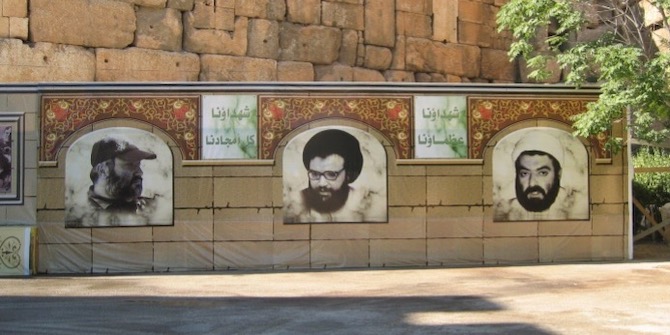

Apparently men of violence have been securing their places at the table. Jaysh al-Islam’s leader Zahran Alloush – blamed by Zaitouneh and Khalil’s families for the abduction of the Douma Four – met Turkey and other governments before his death in 2015. His brother, Jaysh al-Islam’s political leader Mohammad Alloush participated in the 2016 Geneva peace talks. He planned to join regime officials in Russian and Turkish-backed peace talks in Kazakhstan last year but rebels boycotted the meeting. Recently, while a civilian population sheltered underground Jaysh al-Islam brokered a deal and transported Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) fighters and their families out of Eastern Ghouta to Idlib, home to a university Islamicised by HTS, where local women avoid mixing with fighters’ wives.

In Syria ‘peace-building’ has a bad rep. Before the WOW Festival’s panel, ‘Women, War and Peace-building in Syria’ at the Southbank, moderator and Egyptian novelist Ahdaf Soueif explained why: first, because of the term’s colonial associations and, second, because of its use by Israel. I participated on that panel with WILPF’s Alodaat, filmmaker Itab Azzam and 19-year old Syrian refugee Maryam Alhameed, which was heavily attended by concerned members of the public, women activists, FCO officials and a group of Muslim schoolgirls sent by the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change.

Soueif said she follows the Facebook statuses of Nivin Hotary living in Eastern Ghouta. Hotary requested journalism training from Women Now – something that didn’t appeal to major donors. Yet she has emerged as a compelling voice during the siege.

She always writes beside a window covered not by glass but by a plastic sheet. Last month if she had been sitting in her usual spot, with her daughter Maya playing at her side, an explosion would have killed them both. Hotary is still posting by that same window on her laptop as she writes: “to the sounds of surveillance planes in the skies and the sound of shelling coming from I don’t know where.”

Malu Halasa is coauthor of Syria Speaks: Art and Culture from the Frontline and The Secret Life of Syrian Lingerie: Intimacy and Design. Her novel Mother of All Pigs was published in the US in 2017.

Malu Halasa is coauthor of Syria Speaks: Art and Culture from the Frontline and The Secret Life of Syrian Lingerie: Intimacy and Design. Her novel Mother of All Pigs was published in the US in 2017.