by Alice Wilson

Stories and images of revolutions in Southwest Asia and North Africa filled news media during the uprisings and protests of the past decade. The dictators that fell in Tunisia and Egypt, the crackdowns in Bahrain, and the protracted wars in Syria and Yemen are only some of the events through which activists – and their rivals – transformed the region. However, as revolutionaries met with disappointment and backlash, media coverage turned to other stories, movements, and conflicts. Consequently, in the wake of these popular uprisings, questions abound about these revolutions and their denouements: What survives of revolution after disappointment, military defeat, and repression?

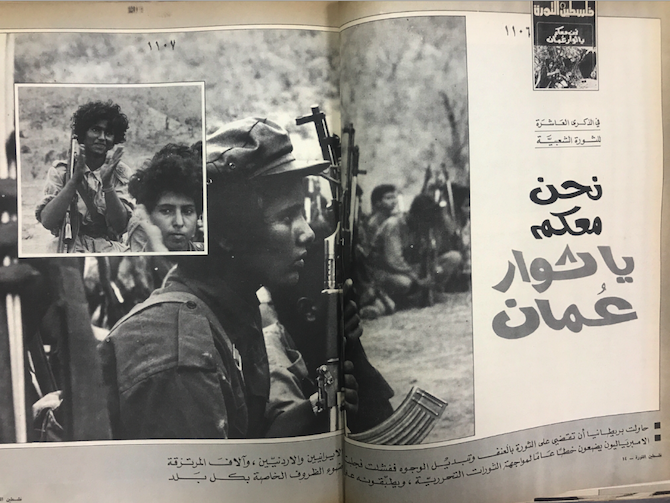

One way of addressing these concerns is to turn to an earlier generation of revolutionaries who met with military defeat and repression. An examination of their post-revolutionary lives can bring to light what survives of revolution against the odds. In Oman, an anti-colonial liberation movement gripped Dhufar, the southern region of today’s Sultanate, between 1965 and 1976. Decades after the movement’s military defeat, the post-war lives of veteran supporters and sympathisers of this revolution show how some former militants reproduce revolutionary values through daily interactions, and more occasional extraordinary acts. These afterlives of revolution have implications for rethinking revolution and counterinsurgency.

Revolutionary afterlives emerged in Oman in the wake of the liberation movement’s pursuit of political and social emancipation. The front fought against the British-backed, Muscat-based al-Busaid dynasty of sultans. At the same time, the movement pursued social emancipation, especially after the leadership adopted Marxism-Leninism in 1968. The front’s strongholds in Dhufar’s mountainous interior and neighbouring socialist South Yemen hosted Maoist-inspired programs for social and gender egalitarianism, the abolition of enslavement, redistribution, health care, education, and development projects. Then, and in later years, these initiatives drew the attention of international audiences.

The British-led, increasingly internationalised counterinsurgency would go on to crush the front militarily, deploying devastating violence. Over the course of the war, the counterinsurgency eventually also scaled up welfare programs for Dhufaris. These initiatives sought to attract Dhufaris’ support but also promoted a more conservative vision of social and political life. After the front’s military defeat, in the post-war decades former militants and sympathisers of the movement found themselves living under the authoritarian rule of the government they had once opposed: the predicament that growing numbers face in Southwest Asia and North Africa today.

Among former militants in Oman, afterlives of revolution take diverse forms. Kinship practices see some erstwhile activists name children, including those born in post-war years, after revolutionary figures of local and global renown. Everyday socialising brings together veteran militants in friendships and informal encounters whose social inclusivity resonates with the revolution’s egalitarian-leaning agendas. Unofficial commemoration – such as funeral attendance following the passing of former militants – marks a revolutionary past and transmits knowledge thereof to later generations. Such unofficial commemoration is part of Omanis’ growing memory work about the revolution that skirts the government’s official silence and censorship concerning this and other episodes of dissent.

In their heterogeneous forms, afterlives of revolution demand a reconsideration of revolution, counterinsurgency, and their aftermaths. Afterlives advance an analysis that decolonises, disrupts, and destabilises conventional narratives.

Afterlives problematise the claims of apologists of the counterinsurgency in Dhufar that a ‘model’ campaign achieved not just military victory, but also ‘won hearts and minds’. At issue is not merely the coercion of the counterinsurgency that severely undermines assertions of a ‘model’ campaign and its allegedly ‘selective’ violence. In addition, claims of ‘winning hearts and minds’ cannot account for the presence of revolutionary values – in kinship, everyday socialising and unofficial commemoration – that outlast counterinsurgency military victory. By problematising depictions of a ‘model’ campaign and ‘hearts and minds victory’, afterlives expose these narratives as attempts to legitimise colonial violence.

Afterlives also reframe inquiry into the nature of revolutionary engagement and social change. They raise the question of how revolutionaries lay foundations for social transformations whose impacts can outlast military defeat and disappointment. Archival materials, eyewitness memoirs, and interviews with former participants point to Dhufaris negotiating their engagement with revolutionary programs. For instance, Dhufaris recall that militant women adopted some styles of clothing associated with revolutionary change while nevertheless rejecting others.

In the light of revolutionary afterlives, these kinds of negotiations do not indicate shaky support for revolution, as sceptics have suggested of Dhufaris. Rather, active choices signal a process of revolutionary engagement and social transformation that is not ‘neat’, but ‘messy’ in the sense that people do not follow scripts. This suggests how radical social change can have lasting legacies not despite but because of the ‘messiness’ of people’s active choices and negotiations regarding revolutionary programs.

Ultimately, afterlives call for an expanded understanding of revolutionary times, spaces, and impacts. Even revolutions that failed to achieve fully the emancipations to which militants aspired have significance beyond the conventional narratives and timelines of military defeat. In Dhufar, socially conservative counterinsurgency welfare policies that had encouraged tribalisation led many Dhufaris to be unwilling to share post-war welfare resources with other tribes. In this context, former militants, whose revolutionary education in the front’s schools had led them to value the ‘common good’ rather than tribal interests, played key roles in delivering local development projects. This shows how revolutionary agency remains significant in postrevolutionary times – even though conventional Sultan-centric narratives of Oman’s post-war modernisation erase former revolutionaries’ contributions.

Moreover, the social values of revolution re-emerge in later platforms for progressive politics. One such legacy in post-war Dhufar was apparent during Salalah’s protests from February to May 2011. Some participants praised demonstrators’ social inclusivity, echoing the aspirations for social egalitarianism of earlier generations of revolutionaries.

A focus on afterlives, then, advances a decolonising analysis of revolution and counterinsurgency by disrupting colonialist, essentialising and exclusionary narratives. Revolutions may depart all too quickly from news media cycles. But their afterlives, and ensuing invitations to reinterpret the past while imagining different futures, survive.

[To read more on this and everything Middle East, the LSE Middle East Centre Library is now open for browsing and borrowing for LSE students and staff. For more information, please visit the MEC Library page.]