by Ruth Mabry and Huda Al Siyabi

In a country where chronic illness like diabetes and heart disease constitute a majority of the disease burden, promoting physical activity (which is a key behavioural risk factor) requires creating inclusive spaces for people to be active. This constitutes one of the four objectives of the Global Action Plan for Physical Activity and involves engaging people of all ages and abilities to address key barriers to physical activity. It is also emphasised in the guiding principles of the Oman NCD policy.

In Oman, communities have illustrated ways in which a participatory planning approach can be used to respond to their needs, including ways to increase opportunities for women’s physical activity. For example, ‘women only’ gyms and gender-segregated walkways were established through the Healthy Lifestyle Project in Nizwa and the Healthy City Project in Sur. More recently, a neighbourhood in the capitol area is being redesigned to meet the needs of residents of all ages, as part of the Where Oman Walks project. For example, in the Al Hail neighbourhood, which lacks pedestrian friendly spaces, a redesign project is underway which involves changing the public space around a community mosque and its commercial shops to include differentiated pedestrian areas and the provision of trees for shade.

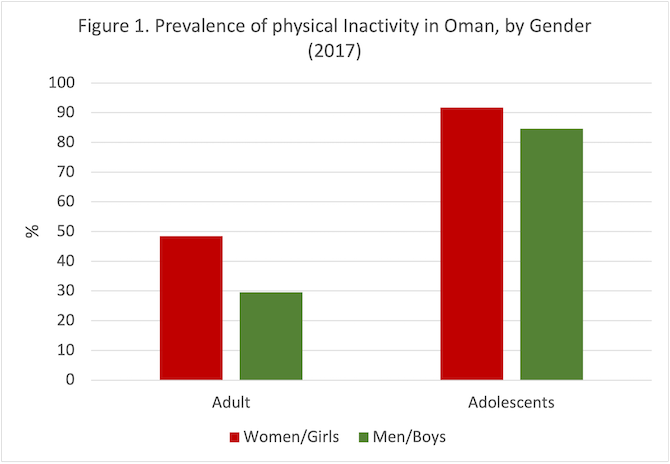

Oman’s rapid socio-economic development since the 1970s, accompanied by increasing rates of urbanisation, mechanisation and motorisation, has resulted in significant demographic and epidemiological shifts, namely dramatic changes in lifestyles and occupational patterns. One measure of these changes is the high level of physical inactivity in Oman, especially among women and children (Figure 1). Indeed, the gender gap, nearly 20% for adults, is much wider than in many other parts of the world. Considering this trend, Oman is aiming for a 10% increase in physical activity by 2025 -an objective more likely to be attained by creating environments that better support physical activity, especially for different sub-populations, such as women.

A mixed-method research project conducted in 2017 on urbanisation and physical activity included interviews with 23 mid-level policy makers from the health, transport and urban planning sectors respectively. The project’s aim was to examine people’s thoughts on building a supportive environment for physical activity based on the draft World Health Organisation technical package, as well as identifying the latter’s policy implications. Women’s access to public and open spaces was one of the emerging themes. It serves as a useful case study to explore how a participatory approach can accelerate efforts to ensure universal access.

The barriers women face, described by respondents, can be grouped into four areas: cultural, psychological, physical, and economic.

Young men would have a chance to do (physical activity) like football, walking, anything they want, they have no obstacles. But for the ladies, they need certain and specific places to walk.

– Interviewee

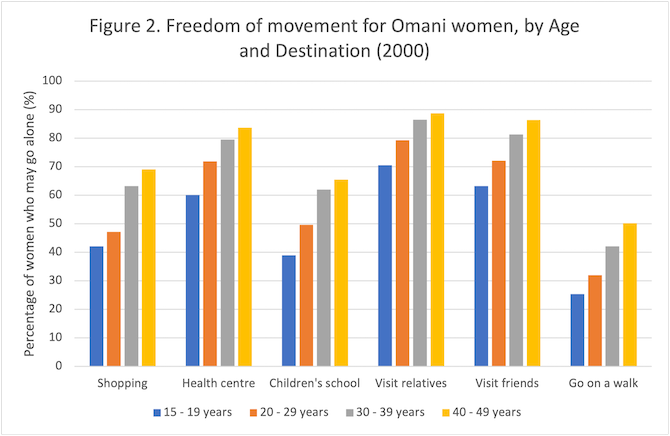

Like other countries in the Gulf, cultural norms strongly influence how women negotiate access and inclusion in public spaces. Many interviewed experts expressed concern about cultural issues that impede on women’s mobility. Women’s freedom of movement in Oman varies with age, with greater freedom for purpose-driven activity linked to family-related responsibilities and their caretaking role. Although Figure 2 illustrates data from 20 years ago, it is one of the few pieces of evidence on women’s freedom of movement in the country. The qualitative work discussed here indicates that women continue to negotiate cultural barriers to mobility.

Several interviewees highlighted their desire to avoid unwanted interactions with men in order to maintain respectability. This issue is especially true for Omani women compared to non-nationals. While Oman is ranked among the safest places in the world for tourists, some public spaces like malls are considered more culturally appropriate than others for Omani women to meet and socialise. This phenomenon is also observed in neighbouring countries. Our interviews also underscored how the fear of harassment and experiencing victimisation, as well as obstacles to road safety, all undermine inclusive access to public spaces.

Indeed, many participants emphasised the presence of physical barriers, such as a lack of sidewalks and a weak public transportation system. Since many Omani women do not drive, this problem is more pronounced, as they would typically depend on others for basic transport needs. The lack of public toilets and other amenities in parks and other open spaces are also common barriers to women’s mobility. Improving urban design elements, such as increasing residential density to enhance street connectivity and broadening land-use mix, are key to promoting physical activity.

In some areas it is easy for women to go outside and walk. In others, it may be more difficult…Culturally, women prefer to have their own space for walking. So if you provide them space, we could get more people walking.

– Interviewee

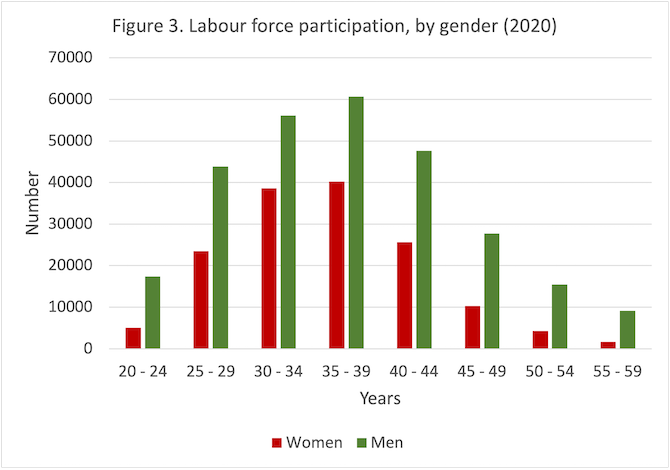

Some interviewees stressed that people cannot afford gym memberships. Despite high literacy rates, only one in three women work in the formal sector, and most of them are relatively young (Figure 3). Meanwhile, a large portion of households do not have helpers to assist with domestic responsibilities, which impinges on women’s potential time for physical activity. This is especially the case for those with larger households, who have young children and/or extended families that live together. Creating gender-sensitive pedestrian infrastructures, such as segregated walking paths, is a key step to ensuring universal access to public space and promoting physical activity.

Rapid urbanisation in Oman has resulted in sedentary lifestyle where chronic diseases contribute to a majority of illnesses and deaths. The prevalence of this pattern is driven by unhealthy dietary behaviours and insufficient physical activity. The urban design model in Oman with functional spatial segregation, high dependence on cars, and single-family villas discourages physically activity. (Re-)designing communities to be more pedestrian-friendly has wide-ranging benefits. As this case study has shown, a participatory approach to planning provides an opportunity to identify the best ways to address cultural, psychological, physical, and economic barriers to mobility for specific segments of the population, especially in a country where such evidence limited.

Note: This blog is based on the Kuwait Programme publication ‘Urbanisation and Physical Activity in the GCC: A Case Study of Oman.’

This piece is part of a series on urban development and the role of road infrastructure in forging socio-spatial conditions, based on contributions from participants in a closed LSE Roundtable in September 2021. Read the introduction here, and see other pieces below.

In this series:

- (Re)thinking Streets in Low Urban Densities by Alexandra Gomes, Apostolos Kyriazis, Clémence Montagne & Peter Schwinger

- The Future Development of the City of Kuwait: Kuwait’s Urban Form as a Case Study by Roberto Fabbri

- Pedestrian Dynamism Index: An Approach to Increasing Permeability between the Peripheral and Central City of Guadalajara by Monica Castañeda, Ricardo Fernandez and Roberto Robles-Arana

- Studying Abroad in Stockholm: Incentivising Young Adults Towards Greener Mobility by Ningning Xie

- Plan with a Purpose: A Systems Approach in Transportation Development and Liveable Cities by Lizao Chen

- Metropolisation and Spatial Segregation in Gulf Cities: The Cases of Abu Dhabi and Dubai by Moiz Uddin

- Rethinking Streets in North Obhur, Jeddah, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia by Alok Tiwari

- Safe and Active Mobility: A Prototype for the Re-Pedestrianisation of Residential Neighbourhoods in Oman by Gustavo de Siqueira

- Urbanisation and Physical Activity: Addressing the Needs of Omani Women by Ruth Mabry and Huda Al Siyabi