LSE Senior Visiting Fellow Claire Milne expresses skepticism about the recent news proclaiming an end to nuisance calls.

LSE Senior Visiting Fellow Claire Milne expresses skepticism about the recent news proclaiming an end to nuisance calls.

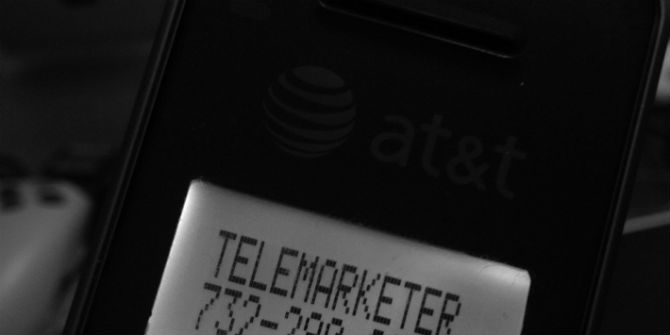

“End of the line for cold callers” shouted the Daily Mail front page. The mail was referring to the DCMS announcement—headed with the claim “Government cracks down on nuisance calling companies”—on the outcome of its consultation last autumn on lowering the legal threshold for Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) to act against offenders. The ICO will no longer be obliged to demonstrate that nuisance calls or texts have caused “substantial damage or substantial distress” before proceeding. Well and good, but Mail readers who expect an end to nuisance calls are likely to be disappointed.

Even the consultation document (whose impact analysis put the cost of this measure at zero for compliant firms) is cautious about likely benefits of the measure, saying that only “potential benefits to consumers may include reduced consumer detriment by reducing the number of unsolicited marketing calls and texts” – a modest enough, and totally unquantified, claim. If the new measure is now worthy of such publicity, shouldn’t government provide some estimate of its likely effect?

And if the case for action is now so clear, and the necessary legal changes can be implemented by April, why has it taken since July 2013, when ICO had already asked for the threshold to be lowered, to get this far? Could the government be spinning out its actions for longer than necessary, to boost their PR effects?

In a presentation last November to the industry standards body NICC, Huw Saunders, Ofcom’s Director of Network Infrastructure, painted a gloomier picture. He identified nuisance calls with a fake or “spoofed” calling number as a major problem, and estimated the number of such calls at 1 to 2 billion a year and growing, as is the number of calls with fraudulent intent. Ofcom’s earlier research into the effectiveness of the Telephone Preference Service (TPS) showed that signing up reduced unwanted calls only by around a third. Some unwanted calls may be legal, but probably at least half of nuisance calls come from companies that ignore the TPS, and who are increasingly likely to spoof their numbers and escape detection.

Saunders explained that Ofcom are working with an international group on technical ways around number spoofing, but that it will take up to 5 years before solutions appear in networks. The best hope he could offer was a UK-only technical solution, which “would at least limit the scale of the problem” and which “might have substantial effect if supported not only by networks but also by consumer education and perhaps by intelligent handset or network screening software”. Ofcom are looking for UK industry to collaborate on this approach, and may consider intervention if progress is too slow. This is definitely an initiative to watch – and again, the UK public deserve to know how much it might reduce the problem.

So what else might be done? My MPP Policy Brief and previous blog posts on this subject already contain other ideas. To build on these, StepChange Debt Charity commissioned me to look at experience of handling nuisance calls in other countries, to see if they had lessons for the UK. StepChange has now published the main report, a volume of country case studies, and its own recommendations in the light of the report, which focus on protecting financially vulnerable people from nuisance calls and texts. I’ll blog again soon about what the report contains and where we might go next.

This post gives the views of the author, and does not represent the position of the LSE Media Policy Project blog, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.