On 13 May 2015, the Belgian Privacy Commission issued a recommendation as part of an ongoing investigation into Facebook’s privacy practices. Brendan Van Alsenoy and Valerie Verdoodt describe why Facebook is facing increased regulatory scrutiny and summarize the highlights of the recent recommendation.

In November last year, Facebook announced it would be updating its policies and terms. Changes were going to be made to the company’s data policy, cookies policy and terms of service. The revised policies and terms came into effect on January 30th, 2015. In the text, Facebook authorizes itself to (1) track its users across websites and devices; (2) use profile pictures for both commercial and non-commercial purposes and (3) collect information about its users’ whereabouts on a continuous basis. Not surprisingly, the announcement was met with some concern and criticism.

Old wine in new bottles?

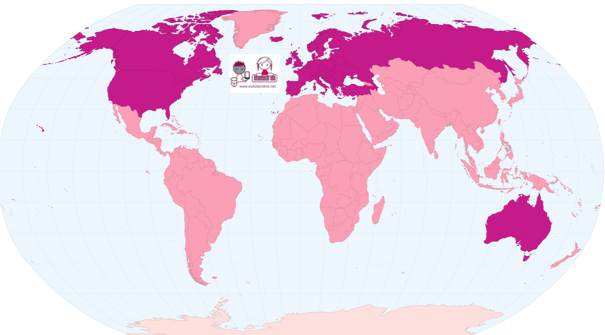

To be clear, the changes introduced in 2015 weren’t all that drastic. For the most part, Facebook’s revised policies and terms are just a repackaging of old practices. Nevertheless, public concerns persisted. Data Protection Authorities (DPAs) across the EU received inquiries from users, the media and politicians. Because the changes affect so many EU citizens (there are approximately 225 million daily active users of Facebook in the EU), the issue became too difficult to ignore. Three European DPAs (from the Netherlands, Belgium and Hamburg) decided to launch an investigation. A few months later, the DPAs of France and Spain announced they would follow suit.

What happens in California, does not stay in Ireland

Facebook has openly questioned the legitimacy of the recent investigations into its privacy practices. According to Facebook, the company should only be subject to the direct scrutiny of the Irish Data Protection Commissioner. Its main legal argument is based on a premise that Facebook Ireland (and not Facebook Inc.) acts as the “controller” in relation to the processing of EU citizen’s data. Facebook Inc., it is argued, is not a “controller” but merely a “processor” acting on behalf of Facebook Ireland. As a result, only Irish data protection should be applicable.

The Belgian Privacy Commission rejected both the accuracy and pertinence of Facebook’s arguments. In reaching its conclusion, the Commission relied primarily on Article 4(1)a of Directive 95/46/EC and its interpretation by Court of Justice of the EU in the Google Spain. Specifically, it considered that Facebook’s establishment in Belgium provided a compelling basis to apply Belgian law because the activities of the establishment are “inextricably connected” to the activities of the (actual) controller, Facebook Inc. The Privacy Commission also recalled that Directive 95/46 did not adopt the so-called “country of origin principle”, but rather recognizes the possibility of cumulative application of national laws.

Facebook tracking through social plug-ins

The second part of the Privacy Commission’s recommendation dealt with a portion of Facebook’s current tracking practices. Facebook tracks the browsing activities of its users even when they are not on the Facebook site through so-called “social plug-ins”, such as the “like” and “share” button. What is more, Facebook also tracks non-Facebook users. Even if you don’t have a Facebook account, a mere visit to a Facebook page – any Facebook page – will result in the placement of a uniquely identifying cookie which will be sent to Facebook (together with the URL of the visited webpage) every time you visit a webpage containing a social plug-in.

Facebook offers its users an opt-out mechanism when it comes to use of tracking data for advertising purposes. As noted by the Article 29 Working Party, however, an opt-out mechanism “is not an adequate mechanism to obtain average users’ informed consent”. The Belgian Privacy Commission examined Facebook’s current practice for obtaining consent and concluded that it did not pass muster. It also concluded that Facebook’s tracking of non-users violates article 5(3) of the e-Privacy Directive.

Recommendations

The recommendations of the Privacy Commission address three different target groups: (1) Facebook; (2) Internet users in general (both non-users and users of Facebook;) and (3) owners of website that integrate social plug-ins offered by Facebook. As far as Facebook is concerned, the recommendation states that Facebook must inter alia:

- provide full transparency about its use of cookies;

- design its social plug-ins in a privacy-friendly manner, so that the mere presence of a social plug-in does not lead to the transmission of information to Facebook;

- obtain opt-in consent before collecting or using information obtained by means of cookies and social-plugins for advertising purposes;

- refrain from systematically placing and receiving long-term uniquely identifying cookies in relation to non-users.

Owners of websites that integrate social plug-ins are reminded of their legal obligations to obtain prior informed consent. The Privacy Commission recommends using tools such as “Social Share Privacy”, both to obtain consent and to prevent unnecessary leaking of information to Facebook. Finally, the Commission advises end-users who wish to protect themselves against tracking to install a browser add-ons, such Privacy Badger, Ghostery or Disconnect.

Looking ahead

A recommendation is not hard law and thus not directly enforceable. It does, however clearly define the position of the Privacy Commission, which considers its guidelines as being “sufficiently clear and substantiated in order to constitute a set of rules safeguarding the observation of the law”. Although the Commission cannot issue fines, it does have the power to seek enforcement through the courts. Moreover, certain provisions it has invoked are subject to criminal penalties, meaning that the Belgian public prosecutor can also initiate legal proceedings.

The Privacy Commission has already announced it plans to issue a second recommendation later this year, in which it will address other aspects of Facebook’s privacy practices. In the meantime, the Commission will continue to work closely with its counterparts in the Netherlands, Germany, France and Spain as investigations progress.

The authors of the blog post are co-authors of a report commissioned by the Belgian Privacy Commission entitled “From social media service to advertising network: A critical analysis of Facebook’s Revised Policies and Terms”. This post gives the views of the author, and does not represent the position of the LSE Media Policy Project blog, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.