As students and citizens across India take to the streets in nationwide protests, Ruhi Khan, PhD Researcher at LSE’s Media and Communications Department, looks at how the striking images of young women protesters are changing mindsets in India, and inspiring men as well as women around the world.

As students and citizens across India take to the streets in nationwide protests, Ruhi Khan, PhD Researcher at LSE’s Media and Communications Department, looks at how the striking images of young women protesters are changing mindsets in India, and inspiring men as well as women around the world.

The face of Indian student protests is a 22 year old history student: Ayesha Renna of the Jamia Millia Islamia University in the capital New Delhi.

A few days ago, students were protesting against what they believe is the draconian Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) and the National Registry of Citizens (NRC) which is believed to be part of a Hindu-nationalist agenda to marginalise Indian Muslims and is considered discriminatory and divisive and against the secular idea of India enshrined in the Constitution.

Renna, along with Ladeeda Farzana and three other women from the same university saved their male friend from brutal police violence and stood up in defiant bravery to confront the men in uniform. The video went viral on social media and journalists from India and across the world rushed to interview the women.

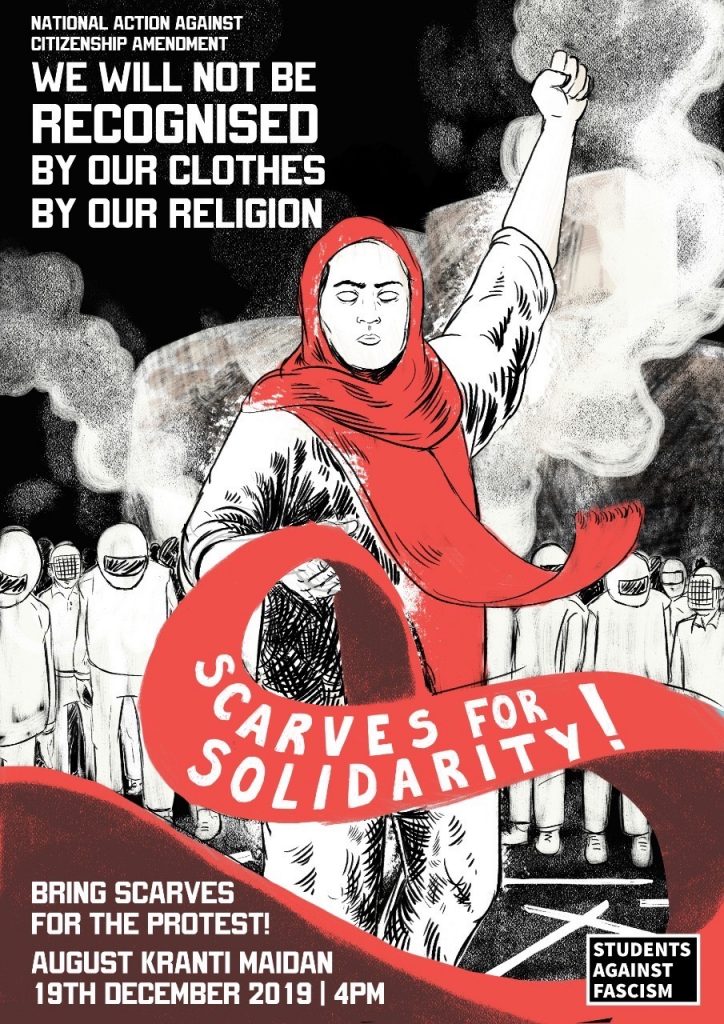

Renna and Farzana became the icons for the student demonstrations. Illustrations of a young bespectacled girl wearing the hijab and confronting the police features in most news media, were circulated widely on social media and even became profile pictures for many. Posters with captions like ‘Fight like a Girl’, give the clearest example of how India has changed.

Renna and Farzana became the icons for the student demonstrations. Illustrations of a young bespectacled girl wearing the hijab and confronting the police features in most news media, were circulated widely on social media and even became profile pictures for many. Posters with captions like ‘Fight like a Girl’, give the clearest example of how India has changed.

The #LikeAGirl campaign by Always, the feminine products company, was started to encourage girls to ‘embrace failure as fuel and to build confidence’. It was all about female empowerment, of embracing girliness and shine. LSE’s Sarah Banet-Weiser, who has written extensively on popular feminism, argues that the danger with these slogans is they end up being all about surface visibility (consumption) and not so much about the intrinsic understanding of the context and taking the politics forward.

Renna’s poster ‘Fight like a Girl’ must not be looked at as just an iconography of popular feminism. It is perhaps not so much about female empowerment as it is about the shameful failure of those perceived more powerful than a young Muslim woman in India today.

Let’s look at how this is changing the Indian mindset:

From cowardice to bravery

For centuries, a way to ridicule men in Indian society and shame them as cowards was to offer them ‘women’s bangles’ to wear. So a woman was a symbol of someone who would run and hide in a difficult situation, who would bow her head and silently concede defeat in a confrontation. Despite India’s history of brave women rulers and leaders, India’s patriarchal society – and Bollywood films – equated a man’s cowardice to a woman’s adornment.

But in the face of danger, knowing fully well how easy it is for the police to act without impunity, these young female students in New Delhi jumped to their male colleague’s rescue, covering him with their bodies, standing strong against men with batons, looking them in the eye and telling then to ‘Stop!’, until they did.

The girls say they were not afraid to die, they are neither afraid of the government nor the unjust police. They re-defined bravery from click-to-support on social media to a physical confrontation in a very dangerous situation. They were threatened and even beaten in the process. There could perhaps be nothing braver that this during any protest. They were hailed as sheroes. They became into a symbolic representation of bravery, an inspiration for men as much as for women.

From subjugation to leaders

Another image that caught public imagination and became the symbol of the movement is of the girls standing tall on a wall, amidst a plethora of protestors with Farzana pointing to the sky, demanding rights and justice.

Another image that caught public imagination and became the symbol of the movement is of the girls standing tall on a wall, amidst a plethora of protestors with Farzana pointing to the sky, demanding rights and justice.

Both Farzana and Renna wear a hijab, often seen as another symbol of the subjugation of women: women in hijab and veils are often essentialised as weak and powerless who need to be saved both from a religious doctrine and a xenophobic society. In reality, Muslim women might wear a veil for various reasons: a reaffirmation of Muslim identity, a commitment to morality, an active declaration of her choice rather than a passive submission to the community. Yet general discourse claims that woman in a veil needs protection and must be freed.

The Triple Talaq (instant divorce) bill, which earlier this year passed through the Indian Parliament, raised several issues about Muslim women’s identity and rights. They were portrayed as helpless, abused by their husbands, lacking agency and in desperate need of help from society. So the images of these two women standing on a wall above hundreds of protestors, raising slogans and demanding rights that benefit all – men and women; rich and poor; Muslim and non-Muslims – shake the very assumptions of Muslim women in India.

Renna says that she stood on the wall to make ‘my voice reach for miles and miles to everyone’. And it did. Not just her voice but also her actions, including her identity as a Muslim woman defending the rights of many others.

Renna says that she stood on the wall to make ‘my voice reach for miles and miles to everyone’. And it did. Not just her voice but also her actions, including her identity as a Muslim woman defending the rights of many others.

It’s pretty clear that the girls wear their Muslim identity with pride. Both girls are married and their parents and husbands support them being at the forefront of the protests. Renna’s husband, journalist Afsal Rahman, wrote on Facebook, ‘I don’t know how much I should bow down before Allah to be blessed with a better half like her. More power to you my girl Renna.’

From spectators to specialists

Lynching in India is a worrying recent trend that is specifically targeting Muslims and other minorities. A study by LSE’s Shakuntala Banaji and PhD Researcher Ram Bhat showed how hate spread through WhatsApp messages linked to mob violence in India.

A look at the video shows it is no different from incidences when men were targeted by lynch mobs. These brave women, who formed a human shield and took some of the beatings themselves, managed to save their friend from what could have been far worse than the bruises he sustained.

Indian author Natasha Badhwar tweeted that the way these girls saved their friend provided a demo of ‘how to rescue a victim during a lynching incident’ thus shaming the many who stayed as silent spectators during the many lynching that India has witnessed recently. The acts of these girls, their fight to save their friend, has also become an empowering cry for the men (and women) in India to save victims of lynching. ‘All we knew was that we have to save our friend and we just did that,’ said Farzana, adding that they were not afraid to get hurt in the process. The girls, conveyed through their actions, that anyone can save lives if only they try to stop the violence they see around them.

And while there are many lessons for men in the stories of these girls, they are no doubt an inspiration to women across the world. The message from these girls is simple:

‘They tell women to stay at home and not speak up, but speak up we must. Nobody can take our voice’.

The protests in India are far from over. They will only intensify over the next few days and weeks. But this is perhaps the first time that a gender-neutral pan-India movement against the very top echelons of power is being led by the (extra) ordinary brave young women of India. They have inspired millions to follow.

This article represents the views of the author, and not the position of the Media@LSE blog, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.