As the world faces a pandemic on a scale not seen for generations, with much of Western Europe, the US and Asia in various degrees of ‘lockdown’ to slow the spread of the coronavirus that causes COVID-19, LSE Professor Myria Georgiou discusses the new digital networks emerging focused on solidarity, and their implications and limitations.

As the world faces a pandemic on a scale not seen for generations, with much of Western Europe, the US and Asia in various degrees of ‘lockdown’ to slow the spread of the coronavirus that causes COVID-19, LSE Professor Myria Georgiou discusses the new digital networks emerging focused on solidarity, and their implications and limitations.

As I am writing this post, we are witnessing incredible levels of citizen mobilisation and acts of solidarity across the UK in response to the coronavirus pandemic. The call from the National Health Service (NHS) for 250,000 volunteers has received a response beyond all expectations, with three times that many people registering online to support health professionals and the particularly vulnerable in just the first few days. Hundreds of local WhatsApp mutual aid networks of solidarity are now active across the country, when only few days ago just a handful existed in London’s inner city.

There is no doubt that the scale of such acts of solidarity is as unprecedented as the pandemic they respond to. There is also no doubt that at times of social distancing, social media make such mobilisation possible, quick and effective. And while we witness these new digital networks of solidarity coming to life, their emergence and focus should come as no surprise.

The scale of digital mobilisation is impressive. The hundreds of thousands joining WhatsApp and Facebook groups of mutual aid initiatives are becoming local activists, rather than just spectators of the crisis. At the time of COVID-19, activism has become hyperlocal and granular – with citizens organising on social media networks for support of those in need and those in isolation in every corner of the country, but most importantly, in every corner of the neighbourhood.

The scale of digital mobilisation is impressive. The hundreds of thousands joining WhatsApp and Facebook groups of mutual aid initiatives are becoming local activists, rather than just spectators of the crisis. At the time of COVID-19, activism has become hyperlocal and granular – with citizens organising on social media networks for support of those in need and those in isolation in every corner of the country, but most importantly, in every corner of the neighbourhood.

As often happens at these extraordinary moments, techno-utopian celebrations emerge around the novelty of digital connectivity. Yet, and while there is no doubt that the speed and the effectiveness of organisation and mutual aid owes a lot to the affordances of social media, the solidarity cultures behind them do not. Having seen many local mutual aid groups coming to life in the last few days, I made three initial observations:

- First, the early and often most active groups emerged in the inner city, that is, in places where local mobilisation and activism have long histories, as the immediate response to the Grenfell Tower tragedy showed during the aftermath of the 2017 disaster. Thus, the new digital street networks build on the histories and knowledge of the material street networks.

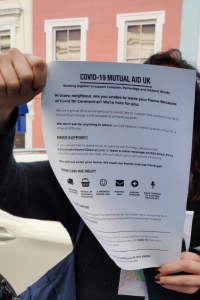

- Second, many of the new hyperlocal activists mobilising at the level of the neighbourhood have been learning activism not only from their neighbours, but also from established grassroots movements. For example, a number of local mutual aid groups in London and eventually the national network Mutual Aid UK, adopted Queercare’s guidelines for supporting those in need without risking spreading infection. These guidelines, among other material produced by grassroots organisations, became key resources for learning and practicing activism in the neighbourhood.

- Third, new alliances from the street to the national level have emerged on social media, as digital networks connected to other networks, linking next door neighbours to one another but also to others across the country. While this translocal connectivity is impressive in its speed and extent, these networks’ primary focus remains on the immediate locale. The most active conversations and mobilisation takes place at the level of the neighbourhood. Thus, the digital response to COVID-19 has been effective precisely because it builds on what we are so used to: communicating, organising and connecting with people we know, or with those our friends know, on social media. But right now, it is happening more intensely, and importantly, collectively, as a response to a new shared challenge.

These of course are no more than initial observations, and solidarity during times of COVID-19 will most certainly attract systematic research in the near future. As I conclude, I want to share a final observation and a question.

The more visible that hyperlocal solidarity becomes, the less visible that solidarity towards those beyond the proximate and the familiar seems to be. As neighbours mobilise to support each other, foodbanks shut down as support and provisions dry out. As life for many at the margins of society becomes even more unbearable in the context of the pandemic, questions are raised about the potentials and limits of digital solidarity. How can the tools and the ethos of solidarity driving hyperlocal activism expand beyond the familiar, to include the stranger?

As I wrote a few years ago, conviviality is not enough if it does not extend to include those who are not already familiar and already socially connected. For those at the margins, a safe home is often unavailable, yet a refuge is needed. This is, for example, the case for women and children experiencing domestic violence, and for refugees living in dehumanising, cramped camps. As the emergence of new networks of mutual support shows, solidarity can digitally link neighbours but it also calls for links with strangers. Building communities of care that include not only the proximate but also those most in need of refuge, remains a work in progress.

This article represents the views of the author and not the position of the Media@LSE blog, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.