As cities become ‘smarter’, with technology used to gather data in various public spaces in order to ‘optimise’ our lives, what does this mean for our civic rights? LSE’s Alison Powell explains some key themes of her new book, Undoing Optimization: Civic Action in Smart Cities.

As cities become ‘smarter’, with technology used to gather data in various public spaces in order to ‘optimise’ our lives, what does this mean for our civic rights? LSE’s Alison Powell explains some key themes of her new book, Undoing Optimization: Civic Action in Smart Cities.

Undoing Optimization explores how city life has been reconfigured by our use and our expectations of communication, data and technologies which use sensors to acquire information, often offering real-time monitoring. The book looks at all three of these kinds of systems, highlighting how their introduction into cities has produced new dynamics around rights, access and civic action. It reminds us that data is not costless, not free from power imbalances and not ahistorical.

The process of technological optimization configures citizenship as an action that, in its ideal form, contributes data to processes that streamline effective delivery of services. This narrows what citizenship becomes, and also intensifies the tendency towards operation decision-making being based on what data is available, and which kinds of outcomes are easiest and most logical to produce. To understand how to imagine, and act, to undo optimization we can focus on the ways that frictions, gaps and errors in sensing provoke different potentials for data in urban life. I outline these dynamics here, and then identify how looking at friction might provide a way of undoing optimization and redefining civic rights in relation to datafied technology. Following anthropologist Anna Tsing’s description of how tense encounters produce relationships of negotiation, I wanted to investigate how misunderstandings and unequal power relations around data might generate new opportunities for social change.

The process of technological optimization configures citizenship as an action that, in its ideal form, contributes data to processes that streamline effective delivery of services. This narrows what citizenship becomes, and also intensifies the tendency towards operation decision-making being based on what data is available, and which kinds of outcomes are easiest and most logical to produce. To understand how to imagine, and act, to undo optimization we can focus on the ways that frictions, gaps and errors in sensing provoke different potentials for data in urban life. I outline these dynamics here, and then identify how looking at friction might provide a way of undoing optimization and redefining civic rights in relation to datafied technology. Following anthropologist Anna Tsing’s description of how tense encounters produce relationships of negotiation, I wanted to investigate how misunderstandings and unequal power relations around data might generate new opportunities for social change.

Technological layers: Networks, Data, Sensing

The experience of the COVID-19 pandemic has given many people first-hand experience of how everyday life links the cause and effect of technologies. Undoing Optimization is about the technologies of urban systems, and the metaphors that have been associated with these. You can also read these dynamics of technological cause and effect into our post-pandemic life of mediated check-ins and online vaccine passports.

What we aren’t always so attentive to is how technologies layer over each other – not only on the ground but also in policy discourse. First came the idea of networks, which arrived through sociological thinking about ‘spaces of flows’ as well as through policies encouraging ‘connectivity’. Then over the last decade, data systems appeared that depended on data-producing, internet-connected infrastructure. Finally, sensing-enabled cities where the dream of integrated systems and constant feedback suggests an attentive, data-logging ‘sensing citizen’.

What I found was that these ideal forms of technological layers in history also generated radical possibilities. There was a lot of policy attention in the late 1990s on a ‘networked citizen’ – or a connected individual engaging with the city, enabled by connectivity – who could also become part of a new market for technology which provides internet access. At the same time, however, networked citizens not only created demand for this access technology, but also reinterpreted access technology as a political project itself. This was the case for community wireless technologies, for example. These networks, which emerged when radio technology became cheap, and while internet access was expensive or inaccessible, not only solved the economic problem of access, they also illustrated another set of political opportunities.

In the case of the data city, network connectivity enabled urban data collection to become a primary mode of aiming to optimize urban life, through processes like collecting data from vehicles and commuters and aggregating it as a means of generating ‘insights’ for governments and transport systems. Yet such data-based optimization can have a narrowing effect, framing the person who continues to use a transport app as a ‘good data citizen’ without addressing the coercive design of these apps. Another kind of ‘good data citizen’ might be a member of a group who audits government data to ‘hold governments to account.’ However, this kind of auditing and oversight can also create a reactionary position for citizens, creating arguments that justify removing funding or support for aspects of urban life that are less easy to render in data. In the book I look at the contrast between the data collected about urban problems on websites like FixMyStreet or SeeClickFix and the long-term, difficult-to-quantify value of community assets like libraries or community centres. The potential of sensing technology, which depends on this interpretation of data as an optimizing technology, also suggests the idea of an ideal citizen who works with sensing technology. For example, the book looks at a pilot project of a citizen sensing project in West Knowle, Bristol. This sensing project emerged out of citizen concerns about how to manage damp within homes. The pilot project addressed issues of damp by integrating data collected by the council with data from sensors installed in some local homes.

The potential of sensing technology, which depends on this interpretation of data as an optimizing technology, also suggests the idea of an ideal citizen who works with sensing technology. For example, the book looks at a pilot project of a citizen sensing project in West Knowle, Bristol. This sensing project emerged out of citizen concerns about how to manage damp within homes. The pilot project addressed issues of damp by integrating data collected by the council with data from sensors installed in some local homes.

Reconfiguring citizenship: the commons, solidarity, and friction

What was most interesting about the Bristol pilot project was that the process of sensing and using sensing data was intended to create a local commons – a space where data could be collected together to be used for shared benefit, and where an approach to problem-solving (called the Bristol Approach) could embed technologies in the process through which citizens define the problems they most want to respond to.

However, the Bristol Approach damp sensor prototype also created a lot of friction. Residents disagreed about how to interpret the data, some wanted to be able to create businesses around the damp sensors and the local council struggled to figure out how to use this data to effectively respond to damp problems in council homes when they no longer employed a damp inspector.

Looking for the appearance of a figure like the commons led me to the third main theme of the book – the way that friction and difference might establish the ground for a different kind of ‘smart city’. This kind of city might not prioritize digital data, since it is clear that doing so encourages constant surveillance as life moments rendered into data are constantly collected. Instead, this smart city might minimize digital data collection and identify places where heterogeneous knowledge could make a difference, and invest in addressing the points of friction. Creating a data commons, for example, does not completely address the logic that underpins the push to treat citizen data as more legitimate than other kinds of civic action, although it can help to identify what’s at stake – even if that might be, for example, the lack of a damp inspector on the council staff.

Coming together in a commons is always a matter of friction. However, this notion can guide us to engage with different kinds of concerns about optimization. The primary among these is the question of ‘for whom is this not optimal’. Addressing this question, in terms of the short term, and the long term, begins to focus some of the questions of justice that come along with the intensification of the current framework of optimization.

Undoing optimization: minimum viable datafication and an embrace of hybrid knowledge

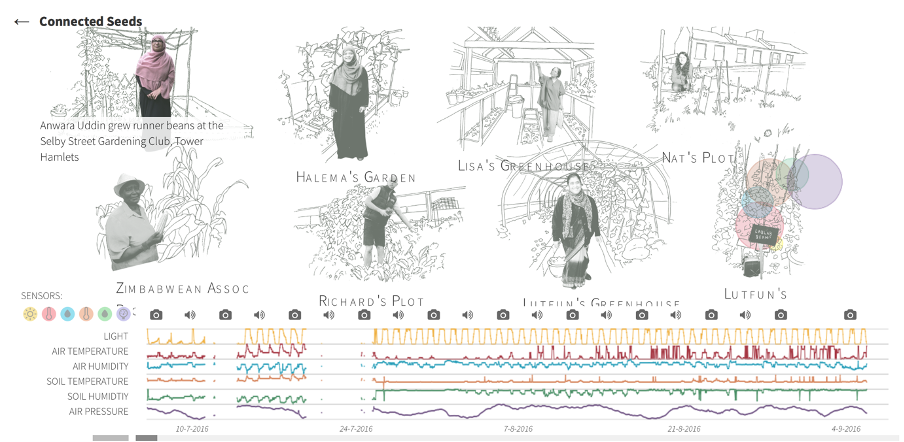

An example of the alternative to optimization is the Connected Seeds and sensors project run by a research team at Queen Mary University of London. The project partnered with the Spitalfields City Farm to investigate what kinds of stories they could tell by combining data about growing conditions with stories about seeds from a number of ‘seed guardians’ growing different sorts of plants in and around the farm. The guardians and their plants came originally from many parts of the world. As part of the project, the team visualised the data in an interactive array that I’ve reproduced here:

This data tells some stories about growing conditions but these are intermittent, fragmentary, sometimes wrong and ultimately not very descriptive. The other stories are descriptive, and detailed, and can be carefully curated, which the data cannot. Something is there, and not there, in it. It is hard to know which of it might be true, although reading the fragments makes it easier to hypothesize when some warm days occurred or when some equipment broke. In the end, it’s a snapshot of a growing season, part of the knowledge that’s both partial and impossible to grasp. The farm is full of hybrids – plants and people that are not supposed to be here, that are not native. They are hybridizing and adapting and transforming the urban world. The completed seed library illustrates how this knowledge can be integrated together.

Here, other kinds of knowing overlap and intersect with the sensor data. Stories of places where seed guardians grew up, reflections about what went well or badly; discussions of the vagaries of growing. The seed library itself, which you can go and see at the farm, unfolds like a giant book and lets you borrow and return seeds, to explore for yourself what you can know about growing food in unusual spaces.

The digital data produced by Connected Seeds sensing systems was incoherent, gap-filled and glitchy, making it difficult to use it alone to register the transformations in plants and people. However, its limitations connected with the richness of the other kinds of information gathered by the gardeners and through the seed library. These frictions once again show how much citizenship cannot be captured by technologically-framed smartness.

Minimum viable datafication

To address the narrowing tendencies association with data-driven optimization, two directions might be generative. First, to consider the politics of smartness as being located in friction, dependent on an acceptance of difference and constant change, and grounded in a principle of generating good relations, both in the present and in anticipation of an unknowable future. This widens rather than narrows how citizens are imagined to be able to participate, opening out the potential for different kinds of civic provision. Second, to advocate for new sets of rights that don’t assume citizens are automatically consumers – for example, the right to minimum viable datafiction – where services are designed to gather less, rather than more data, and where viability over time and across contexts is a primary consideration.

Seeking to create a smart city has valued optimization over friction. Too narrow a sense of smartness has brought us to the brink. Yet civic life, and intelligence, proliferate. Against all odds, we continue to build – together – tenuous commons, from community gardens to traffic-free streets. These can include and exclude, but also generate all kinds of new relations, frictions and connections. The final question is, of course, what solidarity can be built around the frictions we experience?

This article gives the views of the author and does not represent the position of the Media@LSE blog, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Featured image: Photo by Mike Stezycki on Unsplash