Recent research on digital inequalities has focused predominantly on the differences in internet use and digital competencies, while indirectly assuming that inequalities in access to devices and internet connection have been superseded to a large extent. Yet, the coronavirus pandemic showed a different reality when images of children sitting outside fast-food restaurants trying to get connected to be able to do their schoolwork went viral on social media. It quickly became apparent that not all children in Europe are equally able to take advantage of online opportunities raising concerns about the consequences of digital deprivation on children’s education, social connectedness, and leisure activities. In this piece, originally published on www.parenting.digital, Sara Ayllón discusses her recent work on digital inequality in Europe and the role of multiple disadvantages on children’s prospects.

Recent research on digital inequalities has focused predominantly on the differences in internet use and digital competencies, while indirectly assuming that inequalities in access to devices and internet connection have been superseded to a large extent. Yet, the coronavirus pandemic showed a different reality when images of children sitting outside fast-food restaurants trying to get connected to be able to do their schoolwork went viral on social media. It quickly became apparent that not all children in Europe are equally able to take advantage of online opportunities raising concerns about the consequences of digital deprivation on children’s education, social connectedness, and leisure activities. In this piece, originally published on www.parenting.digital, Sara Ayllón discusses her recent work on digital inequality in Europe and the role of multiple disadvantages on children’s prospects.

Internet access is still not universal in Europe

Using data from the EU Statistics on Income and Living Conditions survey (EU-SILC), the DigiGen project explored the extent to which European children and young people may be digitally deprived. We consider children and young people to be “digitally deprived” if they live in a household that cannot afford to have a computer and/or internet connection.

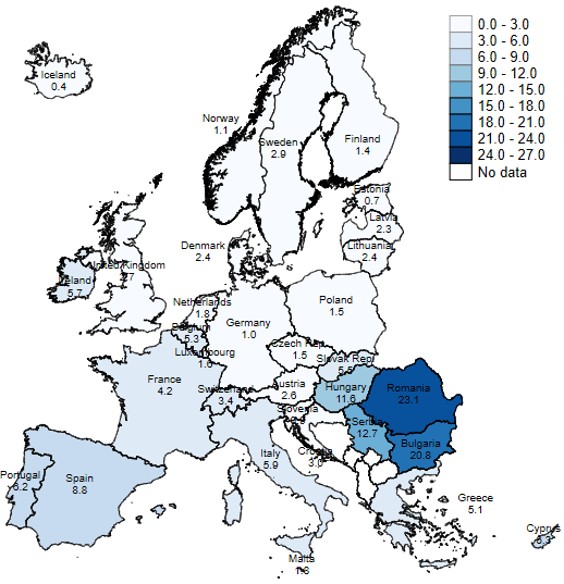

We found that 5.4% of school-aged children in Europe are digitally deprived with substantial differences between countries (see Figure 1). The percentages of digitally deprived children are comparatively low in the UK, Northern and Central Europe, and the Baltic countries but much higher in the Mediterranean countries and particularly in Eastern Europe.

Figure 1: Percentage of digitally deprived school-aged children (6-16 years) in Europe (EU-SILC, 2019)

Further analysis indicates that digital deprivation affects particularly children who live in poverty and severe material deprivation and who have low-educated parents. However, there is large heterogeneity in the characteristics that predict digital deprivation across the countries. For example, having migrant parents of non-European background reduces the likelihood of digital deprivation in Eastern Europe and the Baltic area, while it increases the probability in all other contexts.

Lack of interest and confidence in the use of new technologies create further inequalities

Access to a device and internet connection is a prerequisite for children’s participation in the digital world but the differences don’t end here. Children’s interest in digital technologies and confidence in their digital skills are also of great importance particularly as using digital devices forms an important part of learning.

In the DigiGen project, we also explored the extent to which European children were interested in new technologies and felt confident in using them. We used data from the 2018 wave of the OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) survey to study the role of lack of interest (or disengagement) and the lack of confidence. In particular, we drew on data from the 2018 “ICT familiarity questionnaire” which measured children’s attitudes towards digital media and devices. Only children who had access to digital technologies either at home or at school were included.

Students’ interest in ICTs was measured by responses to the following six statements: 1) “I forget about time when I’m using digital devices”, 2) “The internet is a great resource for obtaining the information I am interested in (e.g. news, sports, dictionary)”, 3) “It is very useful to have social networks on the internet”, 4) “I am really excited discovering new digital devices or applications”, 5) “I really feel bad if no internet connection is possible”, and 6) “I like using digital devices”. The answers were on a 4-point Likert scale, graded from 1 to 4, and were summed up in an overall score for interest in ICT. A score of 12 or lower is considered “digital disengagement”.

Students’ confidence towards ICT was measured similarly by using the answers to the following statements: 1) “I feel comfortable using digital devices that I am less familiar with”, 2) “If my friends and relatives want to buy new digital devices or applications, I can give them advice”, 3) “I feel comfortable using my digital devices at home”, 4) “When I come across problems with digital devices, I think I can solve them”, and 5) “If my friends and relatives have a problem with digital devices, I can help them”. A child is considered to be “digitally unconfident” if they score 10 points or less.

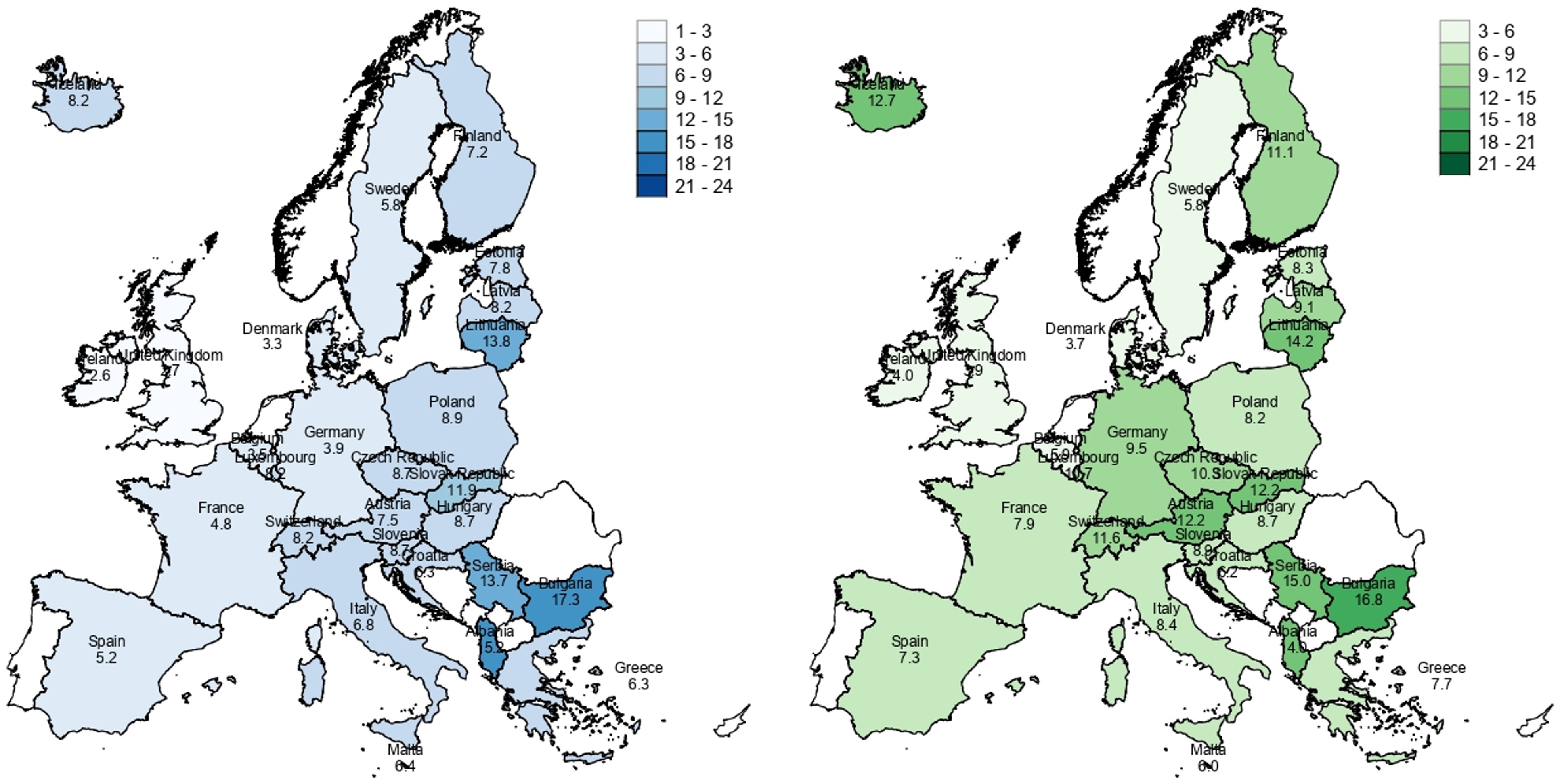

In Europe as a whole, 5.7% of children are digitally disengaged (see Figure 2, left). However, the numbers differ considerably between countries: whereas in Belgium (3.5%), France (4.8%), Germany (3.9%) and Spain (5.2%) the percentages of digitally disengaged children are the lowest, in Eastern Europe digital disengagement is relatively high, with 17.3% of children in Bulgaria and 15.2% in Albania being digitally disengaged. Furthermore, 8% of European children are digitally unconfident (see Figure 2, right). Again, Bulgaria (16.8%) and Albania (14%) have the highest proportion of children who are uncomfortable using digital devices. The proportion of digitally unconfident children is high across most of Eastern Europe and relatively low in Central and Northern Europe, with the exception of Finland (11.1%), Austria (12.2%), and Iceland (12.7%).

Figure 2: Percentages of digitally disengaged children (left) and percentages of digitally unconfident children (right), (15-16 years) in Europe (PISA, 2018)

In spite of the disparities between countries, we find that having to repeat a year and below-average home possessions (i.e. material deprivation) are the main determinants of digital disengagement and lack of confidence.

Divides are interconnected

The results indicate a large heterogeneity across Europe both in relation to the lack of access and the lack of interest and confidence. Importantly, across European countries, the figures for lack of confidence and lack of interest vary in ways similar to the findings for digital deprivation. This is an indication that inequalities of different nature are strongly interconnected creating multiple disadvantages for underprivileged children. Policy initiatives in Europe should seek to enhance children’s digital competencies by simultaneously guaranteeing access and skills – both essential pillars of the educational system nowadays.

This post was first published at www.parenting.digital, and is republished with thanks. This post represents the views of the authors and not the position of the Parenting for a Digital Future blog, nor of the Media@LSE blog, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Featured image: Photo by Annie Spratt on Unsplash