Drawing on their newly published article, PhD Researcher Abel Guerra and Dr. Gabriel Pereira, Visiting Fellow in LSE’s Media and Communication Department, argue that scams are a core feature of the platform economy, just as much as algorithms and data, and that “platform scams” should be defined as the dishonesties and uncertainties behind platforms’ algorithmic management.

Drawing on their newly published article, PhD Researcher Abel Guerra and Dr. Gabriel Pereira, Visiting Fellow in LSE’s Media and Communication Department, argue that scams are a core feature of the platform economy, just as much as algorithms and data, and that “platform scams” should be defined as the dishonesties and uncertainties behind platforms’ algorithmic management.

Imagine you are in an underpaid job trying to make ends meet. The money you make depends on the tasks you receive and complete. You work hard, but as costs keep rising it feels nearly impossible to make it work — uncertainty is not a luxury you can afford at the moment. Yet, every day you are greeted by your “employer” with a promise: if you just perform well, if you just complete a certain number of tasks, then you could get a lot of money. Success is around the corner, as long as you’re resilient enough to pursue it. The promise is unlikely to be fulfilled and all the effort and stress put into the job often turn into frustration.

You may start to feel you are being deceived by this job. An opportunity to make money? Sounds more like a scam. Add some mobile apps, continuously generated data, algorithmic governance, and a lot of hype to the description above, and you end up with a somewhat fair description of the platform economy.

Tech platforms have become a crucial part of our everyday lives and habits: we can use apps to get rides or shop for same-day groceries. What makes this economy tick is a set of algorithms used to organize and assign labor to workers, often all around the globe. In recent years, it has become increasingly evident that these platform workers are not being paid enough, do not have their labor rights respected, and often are made to do illegal or dangerous things to comply with platforms’ demands.

In a newly published article co-authored between six Brazilian researchers, we make the argument that scam is a core feature of the platform economy, just as much as algorithms and data. We argue for the definition of “platform scams” as the dishonesties and uncertainties behind platforms’ algorithmic management.

Uber’s Surge Zone

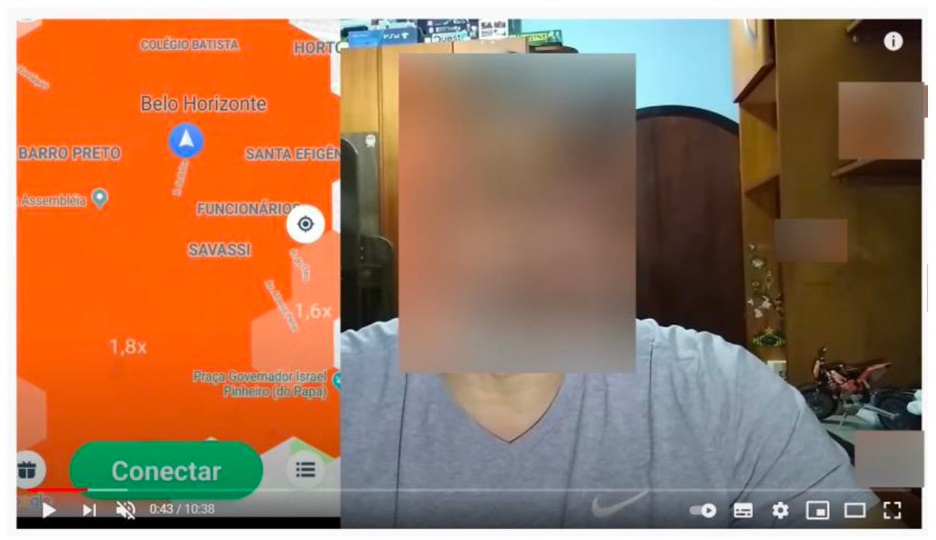

Take the example of Uber, a popular platform for ride-hailing. One of Uber’s features is surge pricing, an algorithmically-induced raise in fares to make drivers’ supply meet occasional high demand levels. In his earlier days as an Uber driver in São Paulo (Brazil), Felipe*, associated surge pricing with a feeling of excitement and the opportunity to earn more. However, just like other drivers, he came to understand that this was “more of an illusion than reality”, as he often receives regular fare rides despite being in a surge area. In other cases, Felipe has noticed surge pricing disappear as soon as he arrives at a surge zone.

One might say Uber is not directly pocketing Felipe and other drivers’ money. However, it is constantly playing an illusion game in which drivers are scammed by an eternal promise of financial gain, spending time and fuel to keep Uber’s wheel rolling. Just like other facets of uncertain and dishonest algorithmic management, this is not an error: surge pricing is in fact operating as intended. It keeps workers hooked and Uber’s finances going. Drivers’ needs, however, are nowhere in sight.

With the concept of “platform scam”, we add to various studies that argue that algorithmic management is currently related to unsafe, unstable, and precarious working conditions. The concept places dishonesty and uncertainty at the core of platforms’ operations and power dynamics. Rather than an undesirable side-effect, platform scam is part how platform labour is expected to work.

The Pushback

To say that platform scams are meaningful doesn’t mean that workers, such as Felipe, just idly accept that they’re being scammed, nor that they are mere pawns in the “platform’s game.” In fact, workers find ways to resist, responding to platform scams through different tactics and strategies. A case in point is Uber drivers’ appropriation of surge pricing as a protest instrument that grants visibility to their demands. During the 2019 global Uber drivers’ strike, Brazilian drivers’ WhatsApp groups were filled with screenshots showing surge’s reddish shade taking over the map of different cities. As drivers went offline, surge pricing kicked in and made the strike visible to drivers, riders and Uber itself. The “bleeding screen”, as one driver put it, was proof that the strike was in fact working and disrupting Uber’s revenue and rider’s experiences. We often hear companies accuse workers of being scammers, taking advantage of platforms and consumers through shady and dishonest practices. Uber, for example, makes sure to communicate to users how hard it works to stop drivers from “manipulating” surge pricing. In the case of the strike mentioned above, Uber went so far as to say that no disruption was caused by workers’ tactics.

We often hear companies accuse workers of being scammers, taking advantage of platforms and consumers through shady and dishonest practices. Uber, for example, makes sure to communicate to users how hard it works to stop drivers from “manipulating” surge pricing. In the case of the strike mentioned above, Uber went so far as to say that no disruption was caused by workers’ tactics.

The pushback from workers is contingent, or as described by platform labour scholars Fabian Ferrari and Mark Graham: an “ongoing cat and mouse game with no clear winner”. This is a game full of asymmetries: platforms, the masters of the game and the owners of the board, get to define what is (il)legal, (ir)regular, and (un)desirable in their systems. They get to change the rules, and from one day to the next the algorithm suddenly works in a different way. Or, even worse, a platform may decide to ban workers with little explanation. This means platforms also have the power to manage uncertainty in ways that push workers not to resist. In the article, besides Uber, we discuss two other platforms: microworkers at Amazon’s Mechanical Turk and click workers at Brazilian click farms. These workers too have to find their ways to “play the platform’s game”, for example by managing different ‘fake’ accounts to be able to perform their tasks.

The experience of workers shows that platforms operate in dishonest and uncertain ways to disadvantage workers, to profit from their labor. The recently released reporting from the Uber files leaks is not a coincidence, but rather an endorsement of the experience of workers we have analyzed. As The Guardian reported, “Uber heavily subsidised journeys, seducing drivers and passengers on to the app with incentives and pricing models that would not be sustainable.”

The lack of sustainability of platforms is not a bug in their system, a mere error or oversight in their operation. As the experience of workers across several platforms shows, it rather is a built-in feature of the platform economy, intrinsic to how platforms are currently designed and operated.

—

This post draws on Grohmann, R., Pereira, G., Guerra, A., Abílio, L.C., Moreschi, B., & Jurno, A. (2022). Platform scams: Brazilian workers’ experiences of dishonest and uncertain algorithmic management. New Media & Society (Special Issue on scams, fakes, and frauds). doi:10.1177/14614448221099225. An open access version of the article is available open access on: https://mediarxiv.org/7ejqn/ . We would like to thank our co-authors Rafael Grohmann, Ludmila Costhek Abílio, Bruno Moreschi and Amanda Jurno for the collaborative effort that resulted in this article.

* Felipe is a fictional driver based on the accounts and experiences of different Uber drivers in Brazil.

—

This article reflects the views of the authors and not those of the Media@LSE blog nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Featured image: Photo by Paul Hanaoka on Unsplash