The influence of businesses’ data-driven algorithm-infused products for education raises concerns about the impact of their commercial interests on the quality of educational opportunities for children and their future life chances. Velislava Hillman, a Fellow in the LSE’s Media and Communications department, who leads a project that drives outside-in audits of EdTech companies to verify their commitment to quality, transparency, and accountability, argues here for a move beyond data privacy principles: it is not just data privacy by principle and design that should mitigate these concerns, but everything that digital products and devices can do and un-do to the learning experience for a child. Beyond the guidelines and toolkits on data privacy by design, the businesses pervading education with their digital products need to be regulated.

The influence of businesses’ data-driven algorithm-infused products for education raises concerns about the impact of their commercial interests on the quality of educational opportunities for children and their future life chances. Velislava Hillman, a Fellow in the LSE’s Media and Communications department, who leads a project that drives outside-in audits of EdTech companies to verify their commitment to quality, transparency, and accountability, argues here for a move beyond data privacy principles: it is not just data privacy by principle and design that should mitigate these concerns, but everything that digital products and devices can do and un-do to the learning experience for a child. Beyond the guidelines and toolkits on data privacy by design, the businesses pervading education with their digital products need to be regulated.

The growing integration of education technologies (EdTech) into children’s schooling has been gathering attention. In particular, it has raised questions in terms of what can be done to ensure trust, transparency, and accountability, given that these products tend to be offered by private companies with business interests. A recent roundup piece reassuringly pointed to 2023 as a year of more educated and critical end-user views towards EdTechs, and there have been reports that schools are increasingly seeking evidence about EdTech’s value to education.

However, to create a trusted relationship between EdTechs and the education community, two major changes must take place: (1) prioritise education over market through top-down regulation and controls, and (2) implement outside-in, bottom-up, and independent audits for trust, transparency, and accountability.

Data privacy by principle, practice, and perplexity

Privacy by design (PbD) visualisations (for end-users of digital products) and PbD guidelines (for developers of digital products) are in abundance. These help individuals to better understand the data collection process and related implications of using digital technologies, emerging extended reality environments, and digital products. However, the growing number and variety of privacy impact assessments, guidelines, frameworks (read about 17 of them here), toolkits, directives (see the new European Union’s NIS2 on cybersecurity or the Department of Education standards) and visualisations are becoming a minefield for technology companies – mature and start-ups alike.

For EdTech companies – and generally all digital service providers targeting children – the confusion is no different. Recent research identified that most start-ups struggle to comply with GDPR’s basic principles, which lack prescriptiveness – what one should do in practice in order to comply – and are therefore subject to interpretation and mistakes. Moreover, much of the attention surrounding data PbD targets large companies rather than tech start-ups. Yet, it is often the start-ups that drive the development, commercialisation, and disruption through their emerging data-intensive algorithmic innovations, while doing so with limited resources and expertise, combined with significant appetite for scale and profit. Such start-ups are especially prevalent in the EdTech sector – and so is their confusion about what they need to comply with.

This sounds messy and it is, for at least three reasons:

- The first can be explained through the Anglo-American neoliberalist way of doing business. It projects small government, which manifests itself in the digital environment. Education is impacted by this, too, as businesses enter its realm with their digital offerings. The role of law and institutions in a neoliberal state act mainly as enablers and defenders of market advancement. In essence, what matters is how the market performs first and foremost. Having said that, regulatory measures targeting the most powerful in the digital sector are certainly growing (see the EU legislative efforts and the US Federal Trade Commission seeking to tackle commercial surveillance and data security). Varied proposals for decentralisation and digital services as utilities have also been debated. However, it is unclear how these will be realised, and how such alternative forms of governance can trickle down to the EdTech sector. Meanwhile, the value that EdTechs extract from amassing education data can be considered excessive and exploitative especially when many of the services are provided for free.

- The second reason precipitates from the first. While some governance is provided through legal frameworks, guidelines, directives, toolkits etc. on data privacy and security, this can distract from seeing any bigger risks of digitising education, or any part of our human existence for that matter.

- Third, there is an overwhelming emphasis on innovation and the potential of technologies for a utopic transformation in education (everyone will be a math genius?) – an obsession with finding technological solutions to social problems. In contrast, and in reality, educational institutions are struggling to cope with all sorts of problems – from teacher strikes, shortages, and demoralisation, to crumbling school buildings, and difficulties providing the most basic necessities for students. These realities, one might argue, remain a secondary consideration when the ideological allegiance falls on the wellbeing of market expansion and technological innovation.

And so PbD guidelines, visualisations, and toolkits limit awareness of the wider societal risks of digitising education or our human existence mainly by providing parameters for the playing field and compliance. Moreover, nothing is said and done about whether any of these products provide substantial contribution to basic human needs and interests. Ironically, narratives around freedom, interests, and rights are often used to parade digital technologies as harbingers of good as they enable education or improve the human experience. But these narratives can also be viewed as an obscure weapon to regulatory immunity – i.e., one must not interfere with or control the companies whose products underpin one’s basic human rights.

Governance by distraction

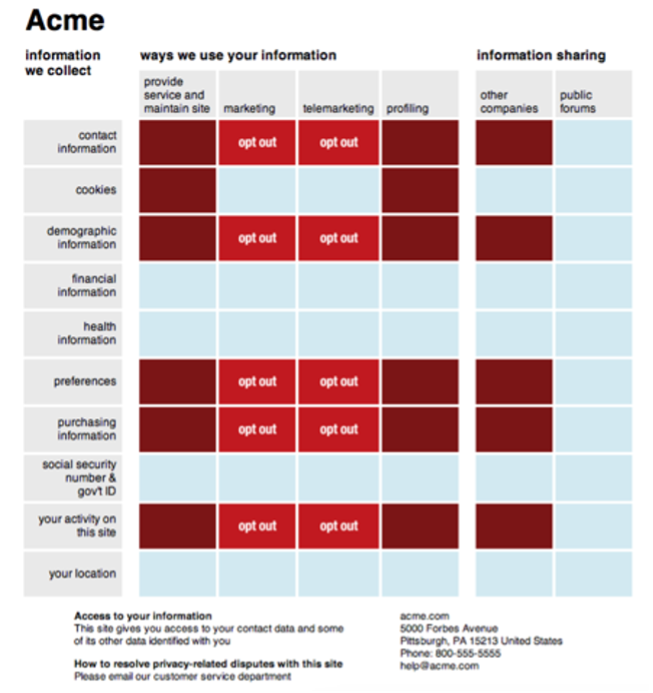

Existing governance of digital technology companies along with PbD guidelines, privacy compliance, and impacts assessments fail to address the power accumulation of private businesses through infrastructure and human capture through data. Furthermore, there is a risk of convoluting the notion that EdTechs mediating educational processes are automatically do-gooders once they display PbD labels of compliance. Many of these guidelines also overlap (Figure 1 for some examples), yet holes remain such as their pedagogic contribution, or their societal, ecological, or health impact.

This is not to deny their importance. However, PbDs risk distracting the attention away from the actual accumulation of data collection and the centralisation of private power. We see higher education infrastructures being captured by American big tech in the UK and elsewhere. The same is happening in compulsory education.

Clockwise from top left: OECD’s privacy wheel; CyLab Privacy Nutrition Label (2010); PbD principles developed by Anne Cavoukian; KnowPrivacy coding methodology (as old as 2009).

Moving forward

Clearly, the current institutional instruments and toolkits available are inadequate to assess harm and impact of the rising pedagogic and authoritative powers of digital technologies mediating all educational processes. Therefore, a distinction must be made from the start: are the existing regulatory measures and oversight prioritising what is best for children or what is best for the market? To this end, top-down efforts should demonstrate clear thinking and decision-making about education regardless of the digital market’s preferences. This will come through clear standards, procedures, and systematic scrutiny of any commercial solutions proposed in education. Clear thinking also means that the obsession with digital solutions should not blind people to all non-digital and equally valid alternatives. In fact, opportunities for learning and future should not be constantly explained through digital projects. Digital opportunities should not replace or eliminate all opportunities.

Outside-in and bottom-up forms of control and oversight should also be encouraged through mandates and welcomed by industry. PbD visualizations and guidelines can be helpful for both users of digital products and their developers. In education, however, these are limited as assessments have yet to cover aspects of cybersecurity, algorithmic justice, pedagogic value, user feedback, duty of care, ecological, and health impacts. These will certainly be work in progress as technologies advance. It is precisely for that reason that measures for building trust, transparency, and accountability should be multi-faceted, independent, and continuous.

Velislava Hillman leads a group of independent researchers and together with EdTech Impact, a UK Organisation that incorporates the Education Alliance Finland methodology on assessing the pedagogic value of EdTech products, are conducting the first full independent audit and assessment of volunteer EdTech organisations across a comprehensive framework encompassing nine vertical benchmarks of verification. For more information contact v.hillman@lse.ac.uk

This article represents the views of the author and not the position of the Media@LSE blog, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Featured image: Photo by Annie Spratt on Unsplash