Anya Jhoti, a communications practitioner, and William Allen of the University of Oxford look at the visual choices that organizations working with refugees make in their online communication, showing how they can both create and break down boundaries between refugees and audiences.

Anya Jhoti, a communications practitioner, and William Allen of the University of Oxford look at the visual choices that organizations working with refugees make in their online communication, showing how they can both create and break down boundaries between refugees and audiences.

Visuals are central to the ways we communicate today, especially on social networking sites. For instance, with over 2 billion active monthly users, Instagram allows people to express themselves and interact with others through image-based posts. Sites and platforms like Instagram play key roles in shaping public understandings of issues and events, while also providing ways for a host of messengers—be they laypeople, influencers, or professional voices—to quickly reach and curate their target audiences at scale. Yet this raises political questions about how messengers represent marginalized groups, and what they aim to achieve by doing so.

This is especially relevant for the refugee support sector, comprising diverse individuals and organizations that are supportive of refugee rights and often engage in advocacy to varying degrees. We examined nearly 200 Instagram posts from five UK organizations (Conversations from Calais, The Worldwide Tribe (now Asylum Speakers), Choose Love, Freedom from Torture, and Care4Calais), complemented by interviews with two staff-members. Prior work demonstrates how digital communication practices create boundaries between migrants and citizens as they determine who is and is not deserving of protection (part of what Lilie Chouliaraki and Myria Georgiou have called ‘the digital border’ in their recent book). This can happen through visual means: experimental studies suggest that depictions of vulnerable refugees, such as children, can foster empathy and move preferences in more positive directions particularly among right-leaning individuals. Yet with a few exceptions (notably David Ongenaert’s agenda examining major refugee organizations’ communications strategies), we know relatively little about the actual visual techniques used in the online activities of the refugee sector.

Communication techniques in the refugee sector: from iconic imagery to takeovers

In our study, we identified how and to what extent these organizations used four techniques in their Instagram posts:

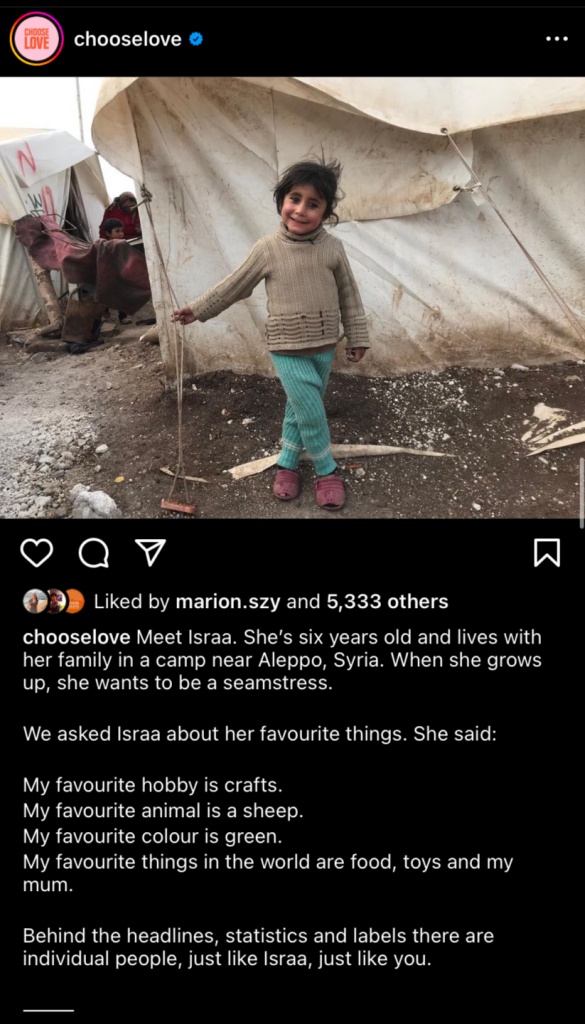

31% of sampled posts, mainly from the accounts of Freedom from Torture and ChooseLove, contained forms of iconic imagery associated with humanitarian tropes such as mother-and-child combinations or lifejackets (see Chooselove post for an example)

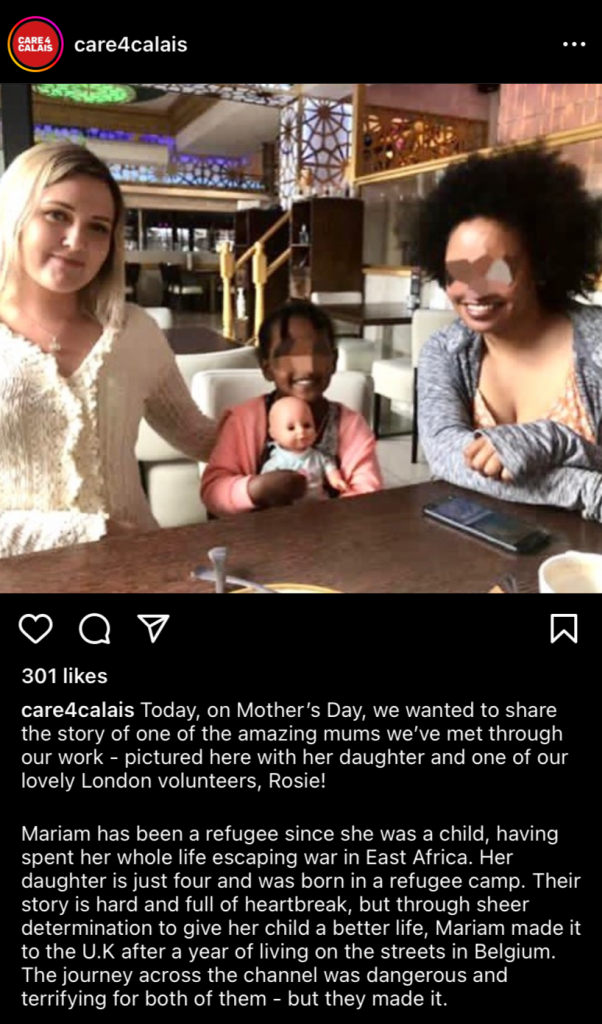

31% of sampled posts, mainly from the accounts of Freedom from Torture and ChooseLove, contained forms of iconic imagery associated with humanitarian tropes such as mother-and-child combinations or lifejackets (see Chooselove post for an example)- 34% of posts containing recognizable human figures had obscured those figures’ identities

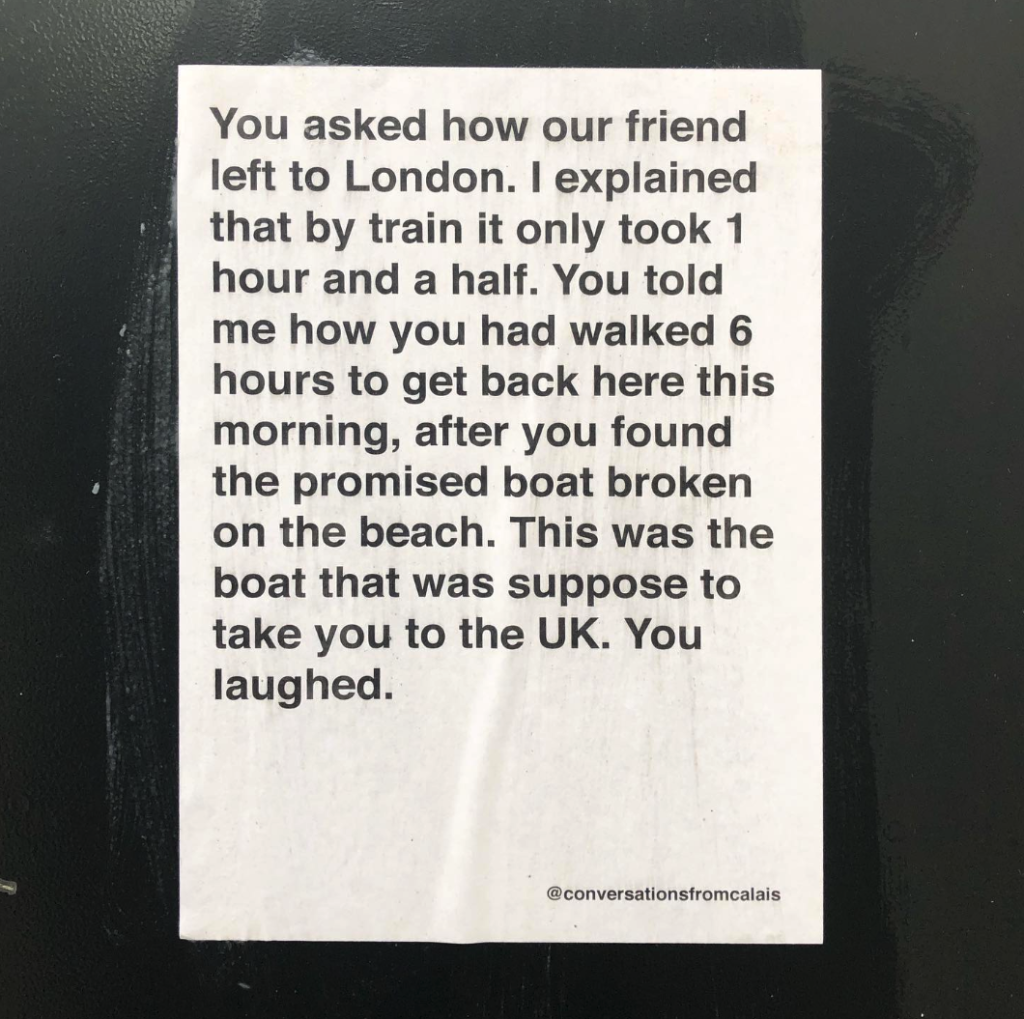

- all the posts from Conversations from Calais followed a format featuring a quotation attributed to a volunteer that had been printed on a poster (see Conversations from Calais post below for an example)

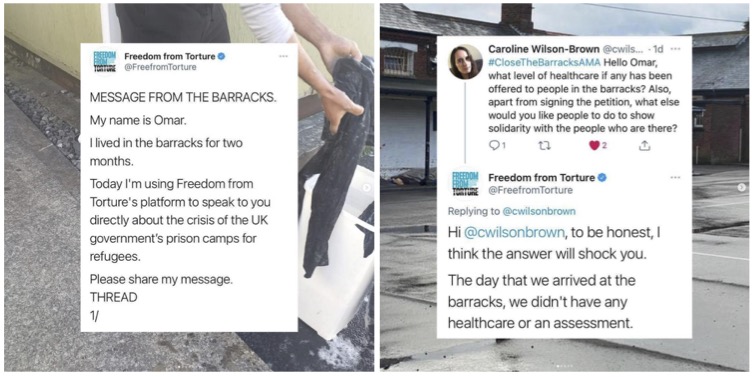

- 41% of posts containing a quotation had explicitly attributed the quote to a refugee, while 6% of sampled images—exclusively from the Freedom from Torture account—were ‘takeover’ posts where a refugee had autonomy over the post (see Freedom from Torture post below for an example)

On the one hand, some of these techniques reinforce symbolic boundaries between viewers (ostensibly Western audiences in refugee-receiving countries like the UK) and the viewed refugee subjects. Stereotypical imagery is particularly prone to doing this: despite criticism from feminist and post-colonial scholars, and growing recognition of its limitations, our evidence suggests the practice of using such images still holds substantial sway in the refugee sector. Moreover, we observed many instances of organizational staff or volunteers speaking on behalf of refugees. Even the practice of obscuring refugees’ faces by blurring them parallels similar visual choices used in popular reporting of criminal activity, which can inadvertently associate refugees with criminality.

On the one hand, some of these techniques reinforce symbolic boundaries between viewers (ostensibly Western audiences in refugee-receiving countries like the UK) and the viewed refugee subjects. Stereotypical imagery is particularly prone to doing this: despite criticism from feminist and post-colonial scholars, and growing recognition of its limitations, our evidence suggests the practice of using such images still holds substantial sway in the refugee sector. Moreover, we observed many instances of organizational staff or volunteers speaking on behalf of refugees. Even the practice of obscuring refugees’ faces by blurring them parallels similar visual choices used in popular reporting of criminal activity, which can inadvertently associate refugees with criminality.

On the other hand, some communication techniques take advantage of Instagram’s digital affordances to represent refugees in alternative ways. For example, the founder of Conversations from Calais explained that the choice to put viewers in the place of a volunteer directly engaging with refugees aimed to encourage greater connection. Meanwhile, takeover posts enable refugees to share their experiences and contribute to their own representations—although this raises questions not only about the levels of digital literacy and organizational capacity required to successfully implement such posts, but also a broader concern that these selected individuals might become stand-ins for all refugees. Even so, as is the case with other platforms, Instagram offers opportunities for more direct engagement with refugee voices that does not happen via intermediaries as can be the case in mass media reporting on migration issues.

On the other hand, some communication techniques take advantage of Instagram’s digital affordances to represent refugees in alternative ways. For example, the founder of Conversations from Calais explained that the choice to put viewers in the place of a volunteer directly engaging with refugees aimed to encourage greater connection. Meanwhile, takeover posts enable refugees to share their experiences and contribute to their own representations—although this raises questions not only about the levels of digital literacy and organizational capacity required to successfully implement such posts, but also a broader concern that these selected individuals might become stand-ins for all refugees. Even so, as is the case with other platforms, Instagram offers opportunities for more direct engagement with refugee voices that does not happen via intermediaries as can be the case in mass media reporting on migration issues.

What contributes to these choices and why do they matter for practice?

Drawing on our visual analysis and speaking with staff-members, we argue that three factors contribute to these patterns. First, practitioners’ understanding of ‘what works’ to increase engagement combine with broader pressures on charities to fundraise. Consequently, images eliciting pity—even if they contain stereotypical (and often gendered) elements conveying vulnerability—might be prioritized to drive donations. Second, the technical affordances on Instagram can impact the eventual effectiveness and visibility of these strategies. For example, while Conversations from Calais serves as a digital archive of refugee experience in Calais, most users view posts via their feeds. This means the conversations are not always viewed collectively as intended. Third, users send signals by engaging with posts: this shapes the eventual reach of individual posts to other users, and contributes to the organizations’ views as to whether a given campaign was successful or not—and thereby the likelihood of similar content in the future.

Refugee-serving organizations are powerful professional voices in the public storytelling of migration, particularly among users already sympathetic to refugees. Their digital content contributes to social norms of acceptable communication that have potential consequences for other behaviours, for example policy making. By documenting the visual choices in this content, and linking them to the ways that they can enact symbolic bordering between the receiving communities and the refugee, we think critical self-reflection on the part of organizations as they develop their communications strategies is warranted. Not only would this foster representation that moves past well-worn tropes about refugees, but also would have the potential to spill-over into broader conversations and then inform more effective types of resistance to the border regime happening both on- and off-line.

This post represents the views of the authors and not the position of the Media@LSE blog, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Featured image: Photo by Karsten Winegeart on Unsplash