Payment by results may meet the same failures Ministers hoped to overcome. Dan Finn suggests that lessons from similar schemes around the world show the risks to service delivery and the need for stronger safeguards for participants.

Payment by results may meet the same failures Ministers hoped to overcome. Dan Finn suggests that lessons from similar schemes around the world show the risks to service delivery and the need for stronger safeguards for participants.

The National Audit Office (NAO) has identified heightened risks to the viability of Government’s flagship ‘payment by results’ Work Programme (WP). The NAO has questioned the accuracy of the projections on which DWP based performance expectations that underpin the funding of the programme; the investment decisions and income of 18 largely for-profit prime providers and their subcontractors; and the services to be received by the 3.3 million people expected to pass through the programme over five years.

Increased unemployment and greater competition for jobs are not the only risks associated with contracts and with paying providers largely on the basis of long term job outcomes. In a review commissioned by the NAO I explored how such risks have emerged and been managed internationally. The WP has unique features but variants of such contracts are now found in a wide range of countries with most evidence from Australia, the USA and the Netherlands.

The positive results highlighted in some assessments suggest that private and third sector contractors have brought innovation and new capacity to service delivery and that competition and payment for performance has generated efficiencies and cost savings. Critics dispute the idea that the conditions for effective competition exist. The transaction costs of designing, awarding, and subsequently managing contracts are high, and the difficulties of managing complex services through performance based contracts have posed risks to service access, costs, quality and accountability.

Closer scrutiny of the ‘welfare markets’ in the other countries raise other concerns. Evidence on the quality and variability of the services delivered is mixed. More positive assessments highlight the enhanced capacity of frontline case managers when they tailor support to individuals and broker job placements with employers. More critical evaluations suggest that providers ‘crowd around’ less costly job search assistance and ‘cream’ and ‘park’ participants. In Australia, for example, the first contracts relied on provider behaviour being driven through differential payments and outcome incentives. The efficiencies gained in the first years were, however, undermined by the emergence of large scale ‘parking’, with providers ‘cherry picking’ the most employable participants to invest in. Subsequently, the Australian Government had to introduce greater specification of service requirements and ‘ring fence’ funding to ensure a minimum spend on participants.

Service user journeys across mixed public and private provision can be complicated, especially for the most disadvantaged. In Australia, the Netherlands and the US problems have arisen with ‘failures to attend’, incorrect assessments, and the imposition of sanctions. Other problems may arise from poor interactions between health assessments and job search and programme activity requirements. Such risks may be heightened with the WP because of its duration, subcontractor delivery chains, and the requirement for participants to maintain regular contact with a private provider whilst continuing to ‘sign on’. Service users will need clear and timely information to avoid ‘mixed messages’ and it will be important to monitor trends in sanctions and the interactions on conditionality between Jobcentre Plus (JCP) and WP providers.

WP prime contractors have specified the varied minimum services they intend to provide and are obliged to inform service users about the services they will make available. There are, however, few safeguards to ensure the delivery of services and DWP will have only limited insight into the ‘black box’ of front line delivery. It is important to ensure that robust systems are in place to respond to complaints of unfair treatment and poor service delivery but the WP approach seems overly complex, with prime contractors having freedom in how they communicate their disputes and resolution procedures to participants and no obvious mechanism for collating complaints information between JCP, prime contractors and DWP. It is important also for DWP to augment current safeguards with methods, such as surveys, that generate greater insight into the experience of participants most of whom will be compelled to participate.

Concerns have been expressed also about the role of third sector organisations and WP prime providers’ management of their subcontractors and the contractual terms and risks they have passed on to smaller organisations. The evidence from the other countries suggest a mixed future with the growth of non-profits that deliver performance or provide valued niche services, alongside a reduction in the number of such organisations involved. In New York City, for example, the introduction of a prime contracting model from 2000 was associated with a ‘shake out’ of community based and smaller non-profits. For some the loss of these ‘less effective’ providers increased efficiency, thereby improving services for participants. Others have argued that participants with special needs may be less well served and that while the loss of many of these local organisations ‘might not show up on a balance sheet’ it undermines the already limited social capital of poor communities.

Each of the three countries has also seen debate about the role of large scale private providers who have emerged as a powerful interest group. In the USA in particular there has been controversy about their operation in certain states (similar criticisms have been made of some of the larger British providers). The US critics cite examples of corporate malpractice, including inadequate and poor provision of services, misappropriation of funds and other financial irregularities. In some US states the organisations involved lost contracts; in others they have taken remedial action and continue to deliver services. Large providers delivering the WP point to the small number of such cases and suggest they are marginal relative to their success in delivering many other contracts and the strength of the organisational, financial and management capacities they bring to the market.

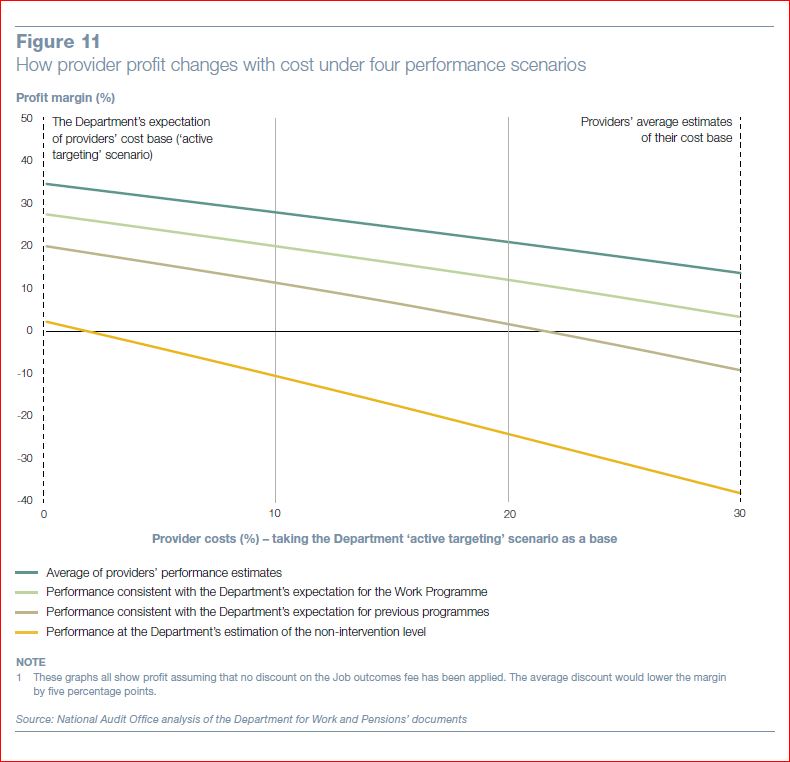

Another particular risk concerns potential for market failure, where providers either go out of business or seek to withdraw from unprofitable contracts and government has no choice but to intervene and either ‘bail out’ a failing provider or quickly find an alternative to continue the delivery of services. The NAO report contains a helpful figure showing potential changes to provider profit that highlight these scenarios (shown below). The earlier ‘Pathways to Work’ contracts, which induced providers to ‘bid low and promise high’, were undermined both by poor design, the impact of the recession, and the speed with which previous Labour Ministers sought implementation, and despite poor performance DWP had to change funding rules to ensure their viability. The NAO suggests there is a danger that the speed of WP implementation and over-optimistic assumptions about labour market performance may reproduce such problems.

Source: NAO (2012) The introduction of the Work Programme (p. 28)

Employment will recover following the return of economic growth but it will be some time before employers start to recruit again in large numbers and many local labour markets face recruitment freezes and redundancies in the public sector. In this context WP providers may struggle to place their service users into sustained employment and to maintain investment in the new service delivery systems and there is a risk that, for the unemployed, the WP may have more in common with the earlier ‘failed programmes’ that current Ministers seek to contrast it with.

Please read our comments policy before posting

The full NAO report on ‘The introduction of the Work Programme’ is available here.

Dan Finn – University of Portsmouth

Dan Finn is Professor of Social Inclusion at the University of Portsmouth. His research interests include the reform of public employment services, activation and the implementation of welfare to work strategies. He has a particular interest in the role of private and third sector providers in delivering employment services and has completed studies of ‘welfare markets’ in the UK, USA, the Netherlands and Australia.

Great article and very interesting to put the UK situation in an international context. The work programme is particularly important for all of us who are looking at payment by results in other contexts. In my case, re-offending and drug treatment. For a range of articles and comments, see: http://www.russellwebster.com/category/pbr-2/