UK public services are delivered in different and complex ways that create confusion for citizens and officials alike. Multiple delivery chains drive up costs, and in the current fiscal climate, they are a luxury good that we can no longer afford. Drawing on recent work for the 2020 Public Services Commission, Patrick Dunleavy and Avery Hancock untangle the mess and argue that more joined-up working, online ‘disintermediation’ of services and working with citizens are needed to carry the UK forward in the digital era.

UK public services are delivered in different and complex ways that create confusion for citizens and officials alike. Multiple delivery chains drive up costs, and in the current fiscal climate, they are a luxury good that we can no longer afford. Drawing on recent work for the 2020 Public Services Commission, Patrick Dunleavy and Avery Hancock untangle the mess and argue that more joined-up working, online ‘disintermediation’ of services and working with citizens are needed to carry the UK forward in the digital era.

In the UK there are currently 13 distinct public service delivery chain patterns, ranging from

– central government services directly supplied to citizens (such as taxation or social security)

– through mediated central government services (such as primary care trusts and NHS hospitals in England)

– to local government or devolved and regional government services.

This structure is complex enough, but the UK central government is also split up horizontally into 14 vertical silos, headed in each case by a department of state in Whitehall with its attendant ‘departmental group’ of quangos (or counterparts in the devolved administrations). Overall we count at least 40 different and substantively important ways of organising the inter-relationships with citizens across tiers of government in most areas in the UK, each of them with their own distinctive peculiarities, institutional histories and characteristic ways of working.

The costs of this diversity are difficult to estimate. It seems undeniable that the luxuriant proliferation of public service delivery chains entails extra costs for citizens in coping with complexity, as research on citizen redress has clearly demonstrated. Compare the UK with a country like Denmark, where local governments regularly deliver three quarters of all public services by expenditure to their citizens, including social security on behalf of the central government. It seems clear that by this comparison we are currently buying a set of ‘luxury goods’ in terms of the ramifying complexity of our arrangements for service provision.

For example, in England alone we currently have 110 different local library services, and 110 different apparatuses for organizing the management of library services, which are too small to be effective. So they are grouped into numerous different small consortia for book procurement, each involving small numbers of localities, and none of them matching the book-buying power of Tesco or Waterstones. Yet approximately 80 per cent of the stock of public library systems is identical country-wide. If we had library services organised in a different way, maybe with 6 to 10 bigger management services competing for local contracts, we could radically save costs and improve provision (including the local responsiveness of provision) at the same time. The picture of delivery chains and horizontal siloing has been evident to ministers, to Parliament and to devolved administrations and local authorities for many years, since at least the 1999 White Paper on Modernising Government. Particularly on the local level there has been a push toward thinking about public services in a more joined-up way, resulting in the growth of local partnerships that bring different delivery chains together to focus more effectively on child protection, or crime prvenetion or economic regeneration.

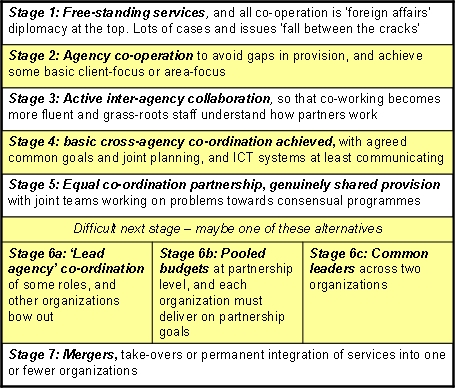

These local-level partnerships have achieved some advances in co-ordinating provision. The chart below shows how joining-up can evolve through stages – although it is possible to skip levels here. But the intermediate forms of partnership here are often costly to operate. In some cases too they can add to institutional complexity in the public sector rather than simplify it. Yet there is a fairly broad practitioner consensus in favour of fostering greater joining-up.

Stages in the development of joined-up services

In addition to organic local-level developments, more top-down or holistic approaches are also being developed in some Total Place pilot areas from 2009. This approach starts by trying to trace the public expenditure that flows down from the central government to distinct city or locality areas. It then invites us to think if we were starting with a blank state, what could be done with the same amount of resources? The coming squeeze on public spending anticipated to 2015 may give this initiative the much stronger impetus it needs to carry forward into significant changes.

Another important stimulus for joining-up public services stems from the need to adapt to the digital era, as the private sector and civil society already have and are still doing at a fast rate. The ability to hold and access the world’s information in digital form may have looked like a utopian dream on the part of Google ten years ago, but it is now clearly an objective (or alternatively a dreaded situation, depending on your point of view) that will in some form be reached in the next decade. The processes that will force the British state to modernise (perhaps often against the dragging resistance of its leading officials and employees across the picture) are not technological but social and economic. In a digital world we cannot afford to consume resources in doing things wastefully or less effectively or less cheaply in the public sector than in the private sector or civil society. It follows from this argument that the government must become a much more critical and expert customer in the market for IT services. As Jerry Fishenden has argued elsewhere on this blog, the coalition government has made an encouraging start here.

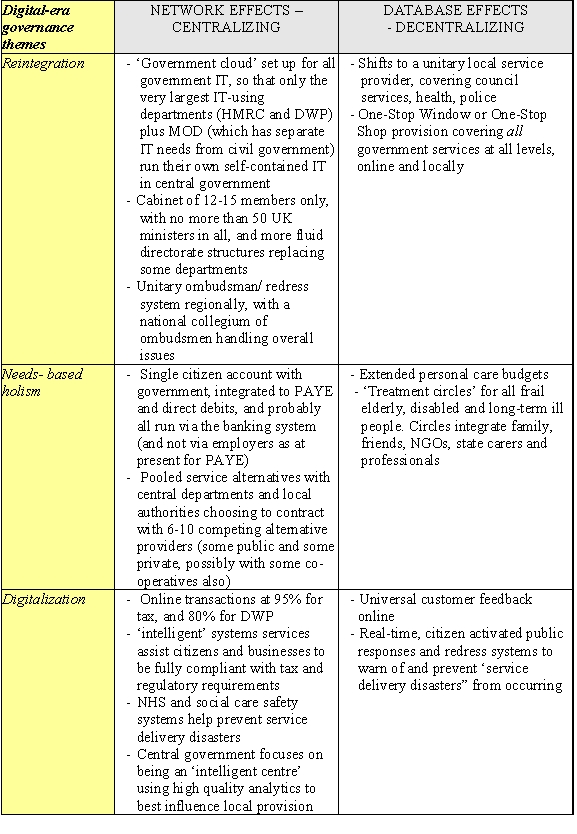

Modern ICT changes cannot be divorced from equally necessary organizational and service-design changes. Research by Luis Garicano, John van Reenen and others highlights both

– the centralizing effects of networking, which allows for more and more data points to be systematised and analysed by fewer decision-makers in real-time

– and the decentralizing effects of modern databases, which means that modernworkers have far more access to information and can make decisions further down the organizational hierarchy.

These two (dialectically linked) trends have dominated the evolution of private industry.

They are strongly present also in the current transition from the ‘new public management’ approach that dominated the UK public services from 1985 to 2005 to the new ‘digital-era governance’ practices. These focus on

– reintegration, by de-siloing and ‘re-governmentalising’ processes to achieve radical simplification,

– needs-based holism, which creats client-focused structures for departments and agencies that can respond in real-time to problems, and

– digitalization, which covers the thouroughoign adaptation of the public sector to imbed electronic delivery at the heart of government.

My second table below imagines some developments in digital-era governance under these 3 themes that seem likely over the next decade. The main directions of travel seem to be towards a UK or England government that serves primarily as an ‘intelligent centre’ for the public sector as a whole, influencing delivery primarily through excellent information rather than seeking to compel adherence to targets or to micro-manage delivery from afar. The centre should also have slimmed down into fewer fixed departments and with more fluid directorate structures merging, such as those used in EU governance or now inside the Scottish Executive. All public services that can do will also have moved decisively online, so that the organization of some major departments like HMRC or DWP will have ‘become their website’ and will relate to all their customers predominantly via digital means.

So far the digital wave has only lapped against some of the roughest edges of public services. It has a great deal of momentum still to run in helping to simplify the landscape of public services in which citizens and businesses operate, and in which government officials and politicians themselves try to understand and positively shape societal development.

So far the digital wave has only lapped against some of the roughest edges of public services. It has a great deal of momentum still to run in helping to simplify the landscape of public services in which citizens and businesses operate, and in which government officials and politicians themselves try to understand and positively shape societal development.

This blog draws on Professor Dunleavy’s essay on The Future of Joined-Up Services,for the 2020 Public Services Commission and funded by ESRC. Full text copies of the essay can be freely downloaded from their website:

http://www.2020publicservicestrust.org/publications/item.asp?d=2602