The government has recently announced plans to reform the Forestry Commission and sell off vast tracts of forest land, in the biggest transfer of land ownership since the Second World War. Avery Hancock takes an in-depth look at the government’s proposals and finds that the move may well expose large areas to exploitation by private developers and drastically reduce our ability to mitigate our C02 emissions.

The government has recently announced plans to reform the Forestry Commission and sell off vast tracts of forest land, in the biggest transfer of land ownership since the Second World War. Avery Hancock takes an in-depth look at the government’s proposals and finds that the move may well expose large areas to exploitation by private developers and drastically reduce our ability to mitigate our C02 emissions.

The Comprehensive Spending Review dealt the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) a double blow with 29 per cent overall cuts and a reduction in quangos from 92 to 39 – the largest imposed on any department. Defra’s response was to abolish the Advisory Committee on Packaging, the Agricultural Dwelling House Advisory Committees and the Darwin Advisory Committee, whilst also transforming British Waterways into a new waterways charity. However, of greatest future import was the decision to retain and substantially reform the Forestry Commission.

The Forestry Commission was originally set up to address the timber shortage after the First World War but its role has since broadened to include conservation, environmental and recreational objectives (it is the UK’s largest single provider of recreation). It currently owns 18 per cent of England’s wooded areas; more specifically 198,298 hectares of freehold land and 57,692 hectares of leasehold land (the Commission’s assets in the devolved regions are controlled locally). But its ownership may shrink to 9 per cent if the Department goes ahead with plans to sell off half the country’s forests in the next few years. According to the Guardian, Defra secretary Caroline Spelman will soon lay out plans to raise up to £5 billion from the sale.

Rumors of the sale prompted widespread concern from environmentalists and rural associations to ramblers and mountain bikers that ‘national treasures’ could be sold to golf-course developers, Centre-parc style holiday villages or even to logging corporations. The Green Party’s MP Caroline Lucas told the Guardian, ‘”If this means vast swathes of valuable forest being sold to private developers, it will be an unforgiveable act of environmental vandalism. Rather than asset-stripping our natural heritage, government should be preserving public access to it, and fostering its role in combating climate change and enhancing biodiversity.”

In an effort to head off such criticism, Defra minister Jim Paice wrote a letter to all MPs explaining that the ‘modernisation’ of forestry legislation in the Public Bodies Bill is part and parcel of the Big Society agenda and that giving individuals, businesses, civil society organizations and local authorities a bigger role in forest management will not compromise the protection of ‘our most valuable and biodiverse’ forests.’ He emphasized that the commission will continue to control licenses for tree-felling and that public rights of way and access will not be affected. A private investor interviewed by the Guardian claimed that the various restrictions reduce the price of potential plots by up to 80 per cent, thus raising the question: how much will the government actually gain from the sale, and at what cost?

The proposals amount to the biggest change of land ownership in Britain since World War II, and follow on from earlier failed attempts, most recently by the Treasury under John Major, to privatize the land. The Telegraph’s Geoffrey Lean argues that land could be bought for tax break purposes – in turn denying the government a significant stream of revenue.

The private management of forests could also hinder broader public interests by halting the planting of trees. Last year the ‘Read Report’ issued by the Commission made a strong case for increasing the woodland cover in the UK, which acts as a sort of carbon ‘sink’ and can make a significant contribution to meeting the UK’s challenging emission reduction targets; currently set by the 2008 Climate Change Bill at an 80 percent reduction of green house gas emissions in the UK by 2050, and reductions in CO2 emissions of at least 34 percent by 2020. A host of other government documents back up the importance of both reforestation and soil in capturing emissions, including the Met Office’s Eliasch Review and the Stern Review,

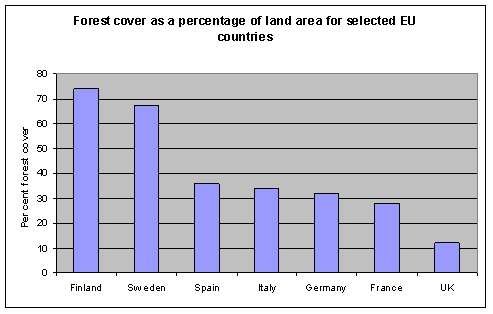

The Read Report argues that, combined with woodlands planted since 1990, creating an additional 23,000 hectares of woodlands over the next 40 years could mitigate 10 per cent of carbon emissions. This would increase forest cover in the UK up by 4 per cent up to 16 per cent, which, as Figure 1 below shows, is still well below the European average.

Source: Combating Climate Change: A Role For UK Forests, UK Forestry and Climate Change Steering Group 2009

Of course these countries are all larger than the UK but this only makes it even more important that our assets are managed wisely. The report recommends that the regulatory framework and sustainability standards are maintained and adapted to address climate change, and that action is taken quickly; as forests themselves are beginning to show signs of the impacts of climate change. There are no guarantees that private buyers or even civil society organizations would be committed to ‘restocking’ our forests.

The Coalition’s plans are still in development and may include ‘conservation credits’ or a ‘national campaign to increase tree-planting by the private sector and civil society.’ In the election campaign all parties said they were committed to planting more trees (who would be against that?) with the Conservatives even pledging to plant one for every child born in England after 2013. But where exactly will these trees be planted? Spelman waxes lyrical about the benefits of planting trees in inner London– where each tree is calculated to be worth as much as £78,000 in terms of its benefits. But according to research in the US, where forests offset about 11 per cent of industrial greenhouse gasses, it is the density and age of forests which matter most. It is also the case that national forests tend to capture more carbon than private ones per acre.

The spending review outlines a number of expensive mechanisms for tackling climate change, such as contributing almost £3 billion to international climate finance and up to £1 billion of investment to create one of the world’s first commercial scale carbon capture and storage demonstration plants. But protecting our forests and valuing the contribution they can make to tackling climate change has unjustifiably slipped down the agenda. This should be rectified both for the short and long term public good.

Click here to respond to this post.

Please read our comments policy before posting.

Here are a few links

A petition

http://www.38degrees.org.uk/page/s/save-our-forests#petition

And a campaign website

http://saveourforests.co.uk/