The UK’s housing crisis is particularly acute by international standards. Instead of identifying real solutions, argues Paul Cheshire, policy-makers have offered only rhetorical devices, ineffective local mechanisms, and magic solutions they cannot deliver.

As a post-truth politician, Michael Gove has a fine track record: he was still claiming the Iraq War a “proper British foreign policy success” in 2008; as a Brexit spokesman in 2016 he stridently dismissed expert opinion from economists. And now he is in charge of housing, which seems likely to turn out as well as the previous two episodes did.

Housing policy as promoted (and attacked) by the present government presents a real problem for an LSE academic who actually takes the institution’s motto of “understanding the causes of things” seriously. Fact and evidence seem irrelevant, not just in the formation of policy but in the claims our politicians make.

Fact and evidence seem irrelevant, not just in the formation of policy but in the claims our politicians make.

The non-political and serious Centre for Cities recently published a paper showing that, had Britain built houses at a similar rate to comparable European countries, we would have built an additional 4.3 million more houses since 1945. Comparing house-building during the 30 years from 1989 to 2019 with the previous 30-year period reveals a similar rate of accumulated underbuilding. Housing is unaffordable in Britain not because we do not build enough “affordable houses” but because we do not build enough houses. Period. At every price and income level, for all forms of tenure, British housing is appalling value for money.

A crisis of affordability

Prices may be falling now but in a cyclical market like housing, if you make supply less responsive to prices, price volatility increases. The long-term trend of real house prices is up but still we have price downturns, made sharper by inelastic supply.

The Barker Enquiry was set up in 2002 because of concerns about housing affordability. The usual measure of that is the ratio of a median-priced house to median local incomes. Since 2002, affordability in England and Wales has got very much worse. The ratio has increased by a factor of 1.6 and, in the least affordable region, London, it has almost doubled. Londoners may be the richest Britons but their housing is the most unaffordable: the median house in London costs over 12.5 times median earnings. Relative to incomes, the North East is the least unaffordable region with a ratio of 4.91 in 2022. This compares to what is internationally judged as a reasonable ratio of 3. So even our least unaffordable region is unaffordable by international standards.

This increase in real house prices particularly hurts the young and the poor. Housing is now the largest component of household spending – up from 11 per cent of an average household’s spending in 2001-2003 to 17.5 per cent in the most recent two year-period. Proportionately to their incomes, the poorest 30 per cent of households spend twice as much on housing as the richest 10 per cent. For the poor housing is a bigger factor in the cost of living crisis than is food – the item the media focus on.

Toothless regulations

So what has post-truth politics got to offer? To be fair, prior to the Chesham and Amersham by-election when the Liberal Democrats shamelessly smooched the Home County NIMBYs, the Conservatives had, by the standards of the last 50 years, a radical policy. They were proposing to reform the planning system to make it more “rule-based” and less discretionary. This would have reduced uncertainty and weakened the power of local NIMBY lobbies. They had also retained the target of building 300,000 houses a year with the admittedly feeble enforcement mechanism of requiring Planning Inspectors, when there was an appeal against a refusal to permit building, to take account of local housing affordability. The more unaffordable local housing was on the median price to income measure, the more the Inspectorate were required to lean in favour of allowing proposals for “sustainable development”. Hardly a powerful weapon to get more houses built but not unreasonable.

Post-Chesham and Amersham, Conservative backbenchers went ape. Having a rule-based system was claimed to be an affront to local democracy – no matter that the “rules” were locally agreed – and the post-truth warriors trolled the idea of including local affordability in the balance of decision-making as a “mutant algorithm”.

The response has been to abandon a target for house-building while increasing the number of houses it is expected will be built in cities, abandon any mechanism to ensure local authorities permit houses to be built and even, de facto, abandon having plans. We are told there is a “plan-led system” but even as of 2020 only 45 per cent of Local Authorities had a valid plan. And things seem now to be even worse, if Stewart Baseley of the Home Builders Federation is correct in claiming that, “…we have now seen 59 local authorities withdraw their housing plans.” If local politicians are under NIMBY pressure not to allow development, their best tactic is to have no valid plan at all – then any building can be blamed on the Planning Inspectorate.

Rhetorical tricks

The other response is simply to change the definition of “house-building”, make directly misleading claims about how many houses are actually being built or promise a “solution” which – even if remotely feasible (and because of the state of our planning system, it is not) – would take 20 years to arrive. One certainty is that the politician making the promises will not be held to account.

House-building is very cyclical so looking at just one year’s figures is always misleading. The long term trend is very clearly down: from building 249,000 new houses a year in the 1970s to 163,000 a year in the 2010s. It did push up to 200,000 a year for 2020 to 2022 but has since fallen back and 160,000 looks as if it would be a good outcome for 2023.

These are actual houses: new construction. But the government now prefers to quote the numbers of “Net Additions”. These add conversions and change of use but subtract demolitions to arrive at a figure for “new supply”. The problem with these is that not only is a converted shop not a good substitute for a new house but all three of these additional elements respond to local housing shortage. Back in the 1970s, when houses were still being built in numbers, conversions and changes of use averaged 9000 a year but demolitions of obsolete houses were around 63,000. By the 2010s we were averaging 28,000 conversions and changes of use a year but demolitions of obsolete houses had fallen to 11,000.

If the Secretary of State were to boast about the increasing number of shop doorways converted to sleeping spaces, the sleight of hand would be obvious. Recent research shows quite clearly that the importance of temporary accommodation in the supply of “homes” increases as local authorities become more restrictive: that is, like affordability, more temporary homes is a function of the propensity to accept or reject new building.

The only solution to Britain’s housing crisis is radical reforms to release more land for building.

So rhetoric and empty promises substitute for effective policy. The only solution to Britain’s housing crisis is radical reforms to release more land for building. Michael Gove’s July speech re-hashed policies going back to John Prescott’s promised “urban renaissance” or even earlier to the East Thames Corridor; there were even echoes of Harold Wilson’s 1963 white heat of technology. But he offered no deliverable solutions grounded in reality.

The Green Belt conundrum

It is reasonable to blame the Greater London Authority (GLA) for at least some of London’s affordability problem. When Sadiq Khan was first elected mayor he foolishly promised no building on Green Belt land but a big increase in housing targets. This was a piece of magic he could not deliver on since if you want to build more houses you need to have land to put them on.

Indeed the single most important reason for our failure to build enough houses over the past two generations is the restriction on land supply which has become ever more binding since a Conservative government first imposed the Metropolitan Green Belt in 1955. When imposed, London’s Green Belt covered 17 times the area of what was then the administrative unit of London – the old London County Council. It is still the same area stretching from the North Sea coast to the edge of Aylesbury. It prevents building on 23 per cent of the area of the Greater London Council itself: more than half of two London Boroughs are covered by Green Belt restrictions.

As I showed in a paper in 2019, there is enough land of no amenity or environmental value close to London’s commuter stations to build a million homes. But it is designated Green Belt so cannot be built on. Allowing building near commuter stations (not just around London) would not just substantially reduce the shortage of houses and maximise the use of existing rail systems – the greenest travel mode. It would also stop London leapfrogging out all over lowland England as people jump it to find affordable but car-dependent housing space.

That would be a real solution to our housing crisis, which the Labour Party shows just some signs of being open to.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

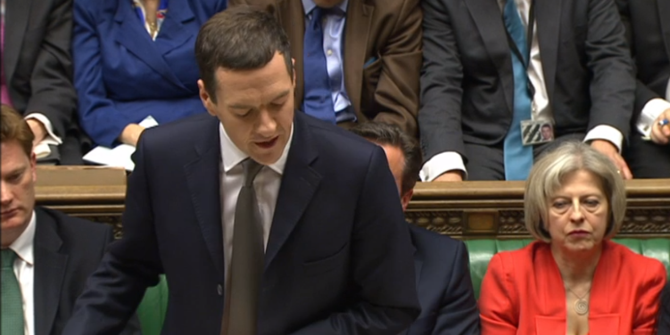

Image credit: UK Government, Creative Commons — Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic — CC BY-NC-ND 2.0