The changes to the welfare cap introduced in the July 2015 budget—which lowers it to £23,000 in London and £20,000 in all other regions—break some of the principles behind the original policy and introduce considerable complexity to the system. In this article, Christine Whitehead and Emma Sagor examine the impact of the changes.

The changes to the welfare cap introduced in the July 2015 budget—which lowers it to £23,000 in London and £20,000 in all other regions—break some of the principles behind the original policy and introduce considerable complexity to the system. In this article, Christine Whitehead and Emma Sagor examine the impact of the changes.

The £26,000 welfare cap for working aged families introduced in April 2013 has been one of the most supported policies introduced by the coalition. By setting the maximum eligibility at the median household income and excluding those working over 16 hours (24, if two workers) voters saw it as an equitable constraint which could, with support, also help people to better their circumstances by finding work.

The evidence of the first 2 years of the policy has been mixed. First, the numbers affected have been smaller than projected and these numbers have fallen quite rapidly to around 23,000 capped households in February 2015, in part because people have indeed moved into in-work benefits and in part because individual circumstances change. In that context the government has been able to claim success – although there are concerns about the quality of the work those affected have found.

On the other hand the impact has been limited by the availability of Discretionary Housing Payments which have compensated many households for losses from the cap – although that help is meant to be transitional. Those affected have mainly been couples and single parents with large families, many of whom are already disadvantaged by living in temporary accommodation. Some 46 per cent have been families in social housing.

The changes introduced in the July 2015 budget—which lowers the cap to £23,000 in London and £20,000 in all other regions—break some of the principles behind the original policy. This could be seen as inevitable, given how few cost savings have so far been generated. Relatively few people have moved to cheaper areas and although the evidence suggests quite large and positive impacts in terms of moving people into work, in-work benefits can often be similar or in some cases even higher.

Most obviously the cap is now well below the median income of working households and will fall further behind over the next few years. Moreover, unlike welfare payments in general which are determined nationally, the policy now has a partial regional element. To some extent this can be seen as desirable as costs vary considerably between regions. Thus, capped households are disproportionately likely to live in London not only because of higher housing costs and the relative concentration of single parents with larger families, but also because they have less purchasing power than capped households in other regions where the cost of living overall is lower. The first result of the new lower cap will be that more households and more household types are brought under the cap – in some cases resulting in single parents and couples with only two children being affected.

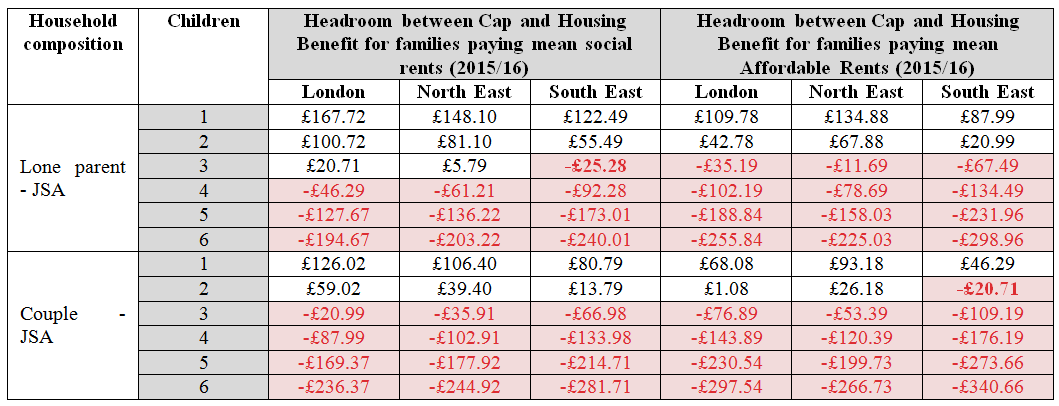

Secondly, it reduces the inequality between Londoners and those living in lower rent regions. Until now London has been disproportionately affected, but under the new regime affected households in the North East—the region with the lowest average rents—tend to be similar to those in London with the lower cap offsetting much of the differences in rents between the two regions. On the other hand, because only London has a higher cap, households in the South East—who on average were the second worst affected before—will now be considerably worse off than similar households in London (see Table, below). This will particularly impact on couples with children, who disproportionately live in the South East and other London commuter areas, which also lose out but to a lesser degree.

Table 1: LSE London modelling – Households capped under July 2015 budget proposal

These welfare changes will undoubtedly reduce the direct costs to government – although not mainly through the reduction in the welfare cap. But they will do so at real cost, not only to the families affected but also to social housing providers and their investment plans as well as to local authorities that have to cope with the fall out if private landlords feel less able to accommodate households on welfare.

Based on the evidence so far there will be more homeless households for whom local authorities have to take responsibility and higher costs relating to both child and adult social care. Other welfare changes announced in the budget will offset some of the effects of reducing the welfare cap, often because households on welfare, whether or not affected by the cap, will lose benefits – so by reducing the amounts that can be claimed some households are kept below the lower cap.

The most obvious offset is the 4-year standstill in working aged benefits which stops any increase in numbers affected by the cap in its tracks once the new levels have been introduced, except those resulting from rent rises. But in the social sector rents are to decline by 1 per cent per annum over the period, again reducing eligibility. Changes to LHA are also constrained – and local authorities have to pay for rises in the cost of temporary accommodation.

The most discussed change has been the removal of child tax credits for the third and later children which applies to those in and out of work but will not impact until 2017. As it is families with three or more children who are currently mainly affected by the cap this will in time significantly reduce the numbers affected by the cap while leaving large numbers of such households working or not working worse off.

But there is also more fundamental cause for concern because the principles underlying the UK welfare system – that everyone should have a minimum income which covers the costs of goods and services identified by the government as basic needs – will be further eroded. The assumption is that people can make choices which either a) increase their income or b) reduce the cost of necessities – especially by moving to cheaper areas. The budget does indeed go some way to helping those in low paid work, but most families on welfare will find the latter entirely unrealistic.

Christine Whitehead is Professor of Housing Economics at the London School of Economics. Her research interests are mainly in the fields of housing and urban economics, housing finance and policy and more general issues of privatisation and regulation. She is an Honorary Associate member of the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors. She has given evidence to the House of Commons Communities and Local Government committee on private renting and the DWP committee on Welfare and housing Costs. In 1991, she was awarded the OBE for services to housing.

Christine Whitehead is Professor of Housing Economics at the London School of Economics. Her research interests are mainly in the fields of housing and urban economics, housing finance and policy and more general issues of privatisation and regulation. She is an Honorary Associate member of the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors. She has given evidence to the House of Commons Communities and Local Government committee on private renting and the DWP committee on Welfare and housing Costs. In 1991, she was awarded the OBE for services to housing.

Emma Sagor is a Research Assistant at LSE London. Her primary research interests include housing economics, planning policy and urban governance.

Emma Sagor is a Research Assistant at LSE London. Her primary research interests include housing economics, planning policy and urban governance.