Despite support for women’s equality, a majority of the British electorate hold sexist attitudes and these attitudes matter when explaining party choice, show Roosmarijn de Geus, Elizabeth Ralph-Morrow, and Rosalind Shorrocks.

Despite support for women’s equality, a majority of the British electorate hold sexist attitudes and these attitudes matter when explaining party choice, show Roosmarijn de Geus, Elizabeth Ralph-Morrow, and Rosalind Shorrocks.

Do attitudes about women matter in British elections? At first glance, we may think this is not the case. General support for gender equality is high: data from the World Values Survey shows that a majority of British people (66%) think that it is an essential characteristic of democracy for women to have the same rights as men. And when asked whether men have a greater right to a job when jobs are scarce, only 6% of respondents agree with this idea. The British population even seems supportive of further action to achieve gender equality: in a February 2022 YouGov poll, 72% of respondents were of the opinion that more should be done to ensure gender-equal pay. This all seems good news for those supporting the rights of women. Yet, as we show in our recent article, despite high levels of support for gender equality, the majority of the British electorate holds sexist views toward women – and these attitudes matter in elections.

The association between sexism and politics has been shown in other contexts, specifically in the case of the 2016 US presidential election. Here, research finds that individuals who hold ‘hostile sexist’ attitudes were more likely to support Donald Trump. The measure of sexism used in these studies is the Ambivalent Sexism Index. This index distinguishes between ‘hostile’ and ‘benevolent’ attitudes. The former reflect antipathy toward women and are measured by asking respondents whether they agree with statements such as ‘Women seek to gain power by getting control over men’. Benevolent attitudes appear kinder to women but reflect male dominance and paternalism and are captured by statements such as: ‘Women should be cherished and protected by men’. Although US scholarship has highlighted the importance of sexism in the 2016 presidential contest, it may be that this was a unique case driven by Hilary Clinton’s historic candidacy; hence, it is unclear whether sexist attitudes matter in different electoral scenarios.

We focused our research on two recent electoral events in Britain: the Brexit referendum and the 2019 general election. In contrast to the US, attitudes towards women – and issues related to women’s rights or gender equality more generally – were not particularly salient or present in these electoral campaigns. Yet, there were reasons to expect sexist attitudes to be important for voters’ choices. The Leave campaign in the referendum focused strongly on the idea of control and showing British strength, both of which have masculine connotations. And previous research found that men who perceived themselves to be discriminated against were more likely to vote Leave. Research has also shown that in the 2019 general election, both Johnson and Corbyn used masculine imagery in their campaigns.

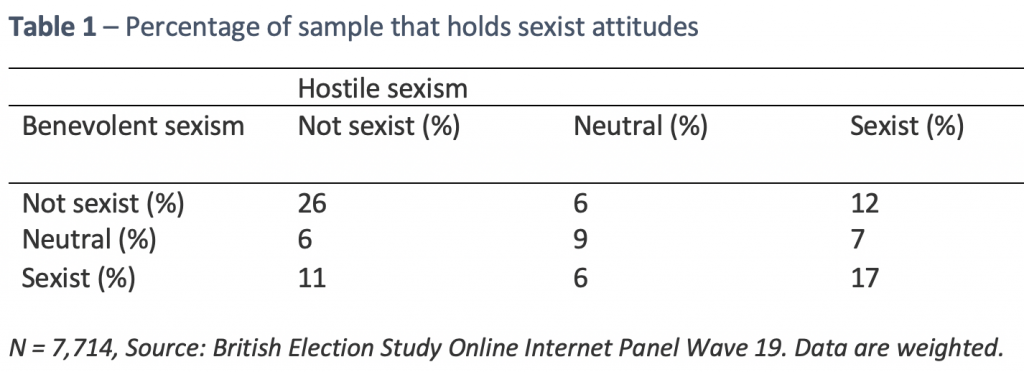

As a first step, we examined the prevalence of sexism in the British electorate and find that more than half (53%) of the sample holds either benevolent or hostile attitudes, or both (Table 1; for more details on the methodology see the original paper). Only 26% of the sample is non-sexist on both indicators.

Men are slightly more sexist than women, but we found much larger differences in levels of sexism between political or partisan groupings than between men and women. Conservative and Leave supporters are more likely to express sexist attitudes (both hostile and benevolent) than Labour and Remain supporters, thereby indicating that there is an important political dimension to these attitudes.

To further explore the political importance of these attitudes, we ran various regression models to test the association between hostile and benevolent attitudes on the one hand, and Referendum and election vote on the other. We find that hostile sexist attitudes correlate positively with voting Leave, but this association disappears once we account for a range of other political attitudes that determined the vote (e.g. immigration attitudes, nationalism).

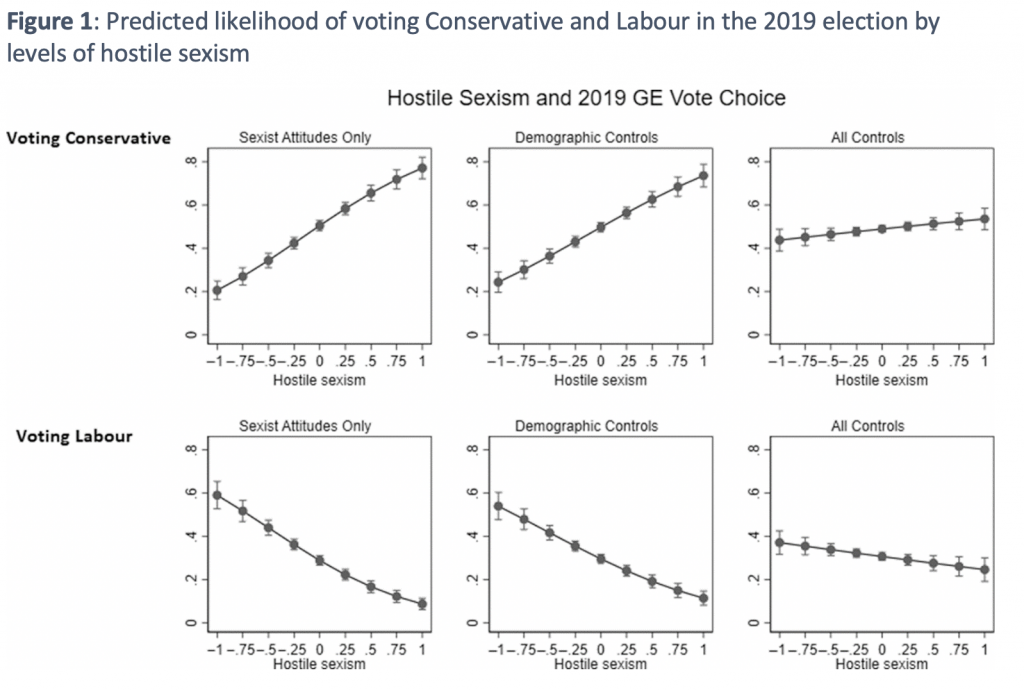

This suggests that sexism did not offer a distinct explanation above and beyond these well-established factors. In the case of the most recent elections in 2019, however, we find evidence that hostile sexist attitudes predict voting for the Conservatives over Labour (Figure 1). The association between sexism and Conservative vote is robust and remains positive and significant even when we control for other important features such someone’s age and education, their attitudes on immigration, and their EU referendum vote. In line with US studies, we find no evidence that benevolent sexism is associated with electoral choice.

Our research thus shows that the association between hostile sexism and voting for right-wing or Conservative political parties holds outside of the specific context of the 2016 US election. This indicates that even when gender is not a salient element of political discourse, political parties may nevertheless be seen as gendered – or associated with men/women and masculinity/femininity – by the electorate. What is more, the fact that both hostile and benevolent sexist attitudes fall along party lines suggests that these attitudes could form the basis of future political cleavages and debates. Our research indicates that even though the British public generally supports women’s rights, sexist attitudes are widespread and electorally significant

______________________

Roosmarijn de Geus is a Lecturer in Comparative Politics at the University of Reading.

Roosmarijn de Geus is a Lecturer in Comparative Politics at the University of Reading.

Rosalind Shorrocks is a Lecturer in Politics at the University of Manchester.

Rosalind Shorrocks is a Lecturer in Politics at the University of Manchester.

Elizabeth Ralph-Morrow is a Lecturer (Teaching) in Qualitative Methods and Political Science at University College London.

Elizabeth Ralph-Morrow is a Lecturer (Teaching) in Qualitative Methods and Political Science at University College London.

Photo by Dan Dennis on Unsplash.