What was the role of masculine imagery in the 2019 UK election campaign? In her analysis of visuals used in tweets, Jessica Smith finds that both Boris Johnson and Jeremy Corbyn used overwhelmingly masculine visuals in their tweets. For Johnson, these centred on masculine locations and associations with masculine figures, whereas for Corbyn they centred on the display of masculine character traits such as agency.

What was the role of masculine imagery in the 2019 UK election campaign? In her analysis of visuals used in tweets, Jessica Smith finds that both Boris Johnson and Jeremy Corbyn used overwhelmingly masculine visuals in their tweets. For Johnson, these centred on masculine locations and associations with masculine figures, whereas for Corbyn they centred on the display of masculine character traits such as agency.

A memorable image of the 2019 UK General Election was Boris Johnson smashing through a wall on a JCB digger emblazoned with his campaign slogan ‘Get Brexit Done’. The image resonated with the ‘bolschie’ masculinity associated by some with Johnson and was an active contrast to the Leader of the opposing party, Jeremy Corbyn, who is known for being a ‘grandfatherly’ figure who makes jam with fruit from his allotment.

These images led me to ask what role masculinity plays in these leaders’ campaigns. Masculinity is often under-examined in current work, with a focus more often on how women may ‘act like’ men to fulfil gendered stereotypes of the ‘good’ political leadership and men usually treated as the norm comparator. Yet, ‘men play the gender card too’, and an examination of the imagery used by Boris Johnson and Jeremy Corbyn on their Twitter accounts during the 2019 campaign demonstrates that.

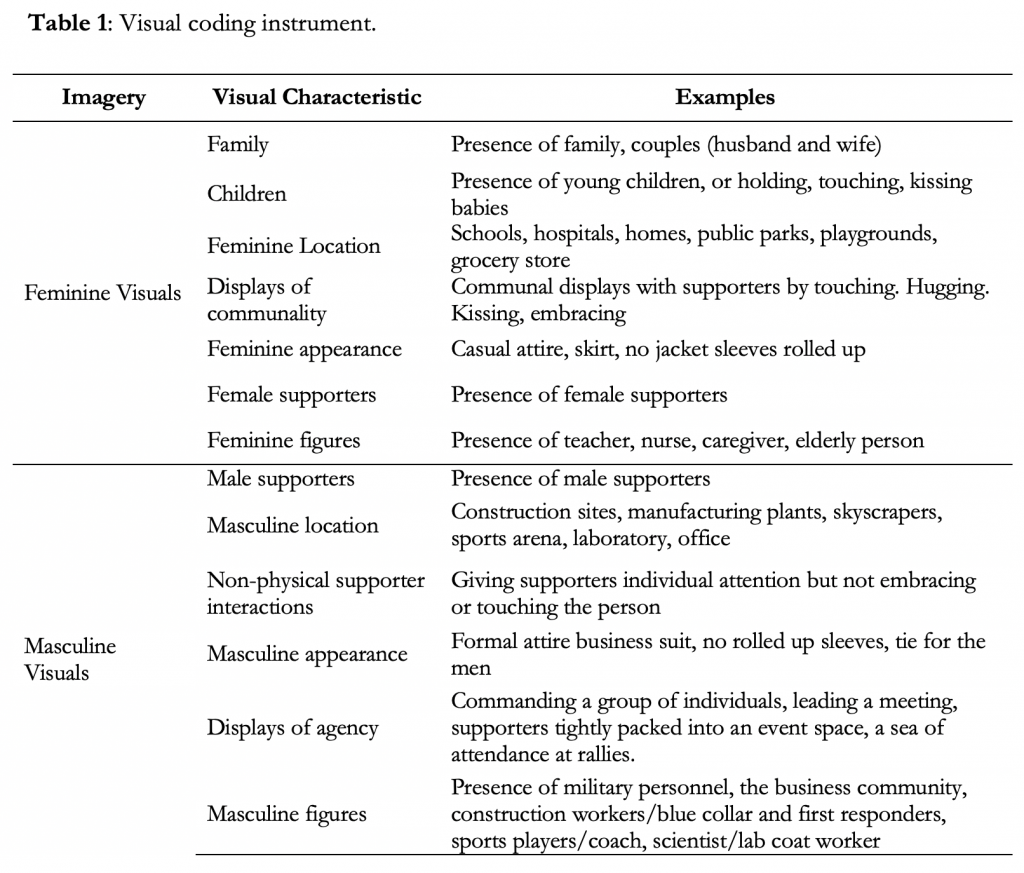

In a recent paper, which is part of the JEPOP special issue on gender in UK elections, analysis was undertaken of the images (or video) tweeted by Johnson and Corbyn during the official campaign period (14 November to 12/ December 2019). Images were categorised as masculine or feminine based on a previous study of visual imagery in US Senate campaign ads. The categories are set out in Table 1.

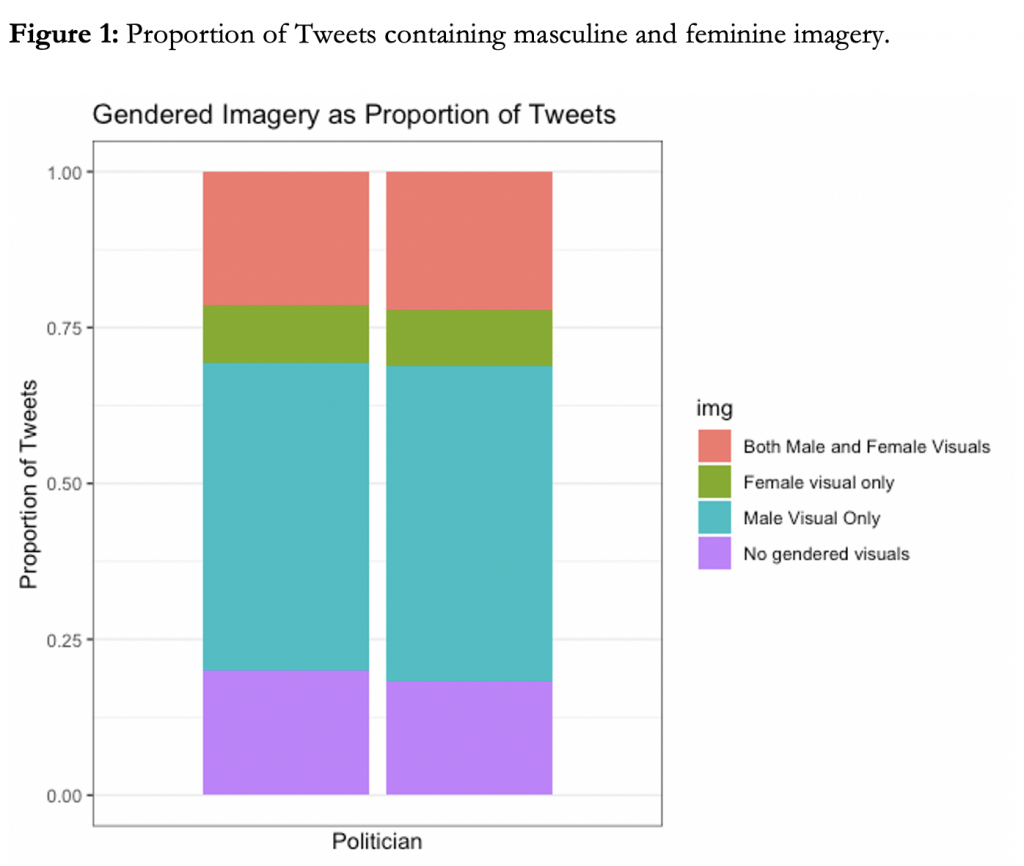

Figure 1 shows the proportion of tweets that included no gendered imagery, any masculine or feminine imagery, or a mixture of the two (only tweets which included an image or video were included).

Masculinity dominated in the images that the leaders used. In total, 81% of tweets included some form of gendered imagery, with 71.5% of tweets including masculine imagery and male visuals only being most common, at similar levels for Johnson and Corbyn (appearance excluded from this analysis as coding all appearance as masculine or feminine could be masking variation in gendered imagery). Feminine images were present in the tweets but at lower levels than masculine, and most commonly would appear in combination with masculine images. Counter to the ‘new man‘ trend in recent political representations of masculinity, few of these feminine visuals included either leaders’ family. This can be seen in Figure 2 which measures the prevalence of the different types of masculine and feminine imagery. A measure of the range of imagery shown in each tweet was also created, and showed that Johnson displayed a significantly higher range of masculine images per tweet than Corbyn (see paper for more detail).

Types of Masculinity

For Johnson, the high level, and range, of masculine imagery was driven by the characteristics of masculine locations and masculine figures. At least one of these characteristics appeared in 31% of his campaign tweets, and these characteristics appeared significantly more often for Johnson than for Corbyn. Johnson used masculine locations and figures to display traditional ideas of masculinity linked to strength and toughness. A common image was Johnson visiting building sites, factories, and warehouses associating him with traditionally working-class, manual and male spheres of work, and physical strength and toughness. Still images, such as those in Figure 3, of Johnson on these visits in his high visibility working gear were an explicit display of masculinity. Johnson’s campaign aligned him with ideas of what I term ‘hypermasculinity’ – an exaggerated form of traditional masculinity. Given Johnson’s elite background, these images can be seen as a more deliberate exaggeration and manipulation on his part. At times, this was an exaggerated and aggressive display, encapsulated by that iconic image of Johnson driving his digger through the wall.

Jeremy Corbyn’s campaign was dominated by masculinity too, with no greater use of femininity than Johnson’s. This was most often seen in clear displays of agency with images of him addressing large crowds, such as Figure 4. Displays of agency appeared in 64% of Corbyn’s tweets, compared to just under a quarter for Johnson, and this difference was significant. Whilst still a clear display of what is stereotypically thought masculine, it was based less on strength and toughness compared to Johnson. Corbyn also had more female supporters present in his visuals and significantly more often interacted communally with supporters. It is hard to separate out the context from these small-N elections. Jeremy Corbyn is known for these big rallies, ‘Corbynmania’ in 2015 won Corbyn – a relatively unknown to the public backbencher – the Labour leadership in 2015. However, Corbyn is also known for pushing a more ‘caring’ and ‘compassionate’ politics and yet, overall, masculine imagery still dominated his campaign.

Although increasingly aware that men ‘play the gender card’, too often political scientists treat masculinity or male candidates as the norm comparator when examining gender’s role in campaigning. An analysis of the visual imagery tweeted by the two male leaders in the 2019 General Election made it clear the men were running as men. Masculine imagery dominated both leaders’ campaign and both most frequently tweeted images including only male visuals. The lack of feminine imagery, especially any using leaders’ family, goes against recent trends in the UK of the ‘new man’ political leader, a more feminised masculinity often seen through hands-on fatherhood. Whether this lack of the domestic marks a movement away from the more feminised ‘new man’ model of leadership remains to be seen, but it suggests that traditional masculinity may still work well for men in politics despite previous movements away from this model. More work needs to be done to fully theorise and test the types of masculinity used in campaigning, the effects of these on different audiences, and the role of partisanship. But this initial study suggests that masculinity remains dominant.

____________________

Jessica C. Smith is Lecturer in Politics at the University of Southampton.

Jessica C. Smith is Lecturer in Politics at the University of Southampton.