Should the popularity of an article determine whether academics choose to blog again? In light of increasing interest in the number of times an article has been read, Artemis Photiadou explains why such information gives only part of the picture, and how it may distract from the many benefits academic blogging offers.

Should the popularity of an article determine whether academics choose to blog again? In light of increasing interest in the number of times an article has been read, Artemis Photiadou explains why such information gives only part of the picture, and how it may distract from the many benefits academic blogging offers.

There is a December tradition for blogs to list their most-read articles of the year. But ranking posts was not clear-cut this year. As ever, much depends on when something was published, with those from the early months obviously doing better. This year we also had more authors than ever before, upwards 320; we had more new contributors than in any of the previous six years; and we saw a boost in the readership overall. All these meant that each of 2017’s articles has been read widely, with many then shared and read beyond our site.

These developments got us wondering whether they are indicative of a growing interest in academic blogs in general, or down to a few pieces we published and which affected our total. We delved deeper into the past few years’ analytics, and 2017’s growth was the result of an increase in returning readers, of a growth in traffic from outside the UK, and of more articles being cited in mainstream media. We cannot pin this interest directly down to Brexit and the daily commentary it generates, because we don’t publish much on that – LSE has a dedicated Brexit blog doing the heavy lifting. Nor did snap election pieces receive more attention that others. Crucially, we are not the exception. There are many politics blogs with an ever-growing presence (the PSA blog and the Institute for Government being excellent examples).

The trouble with numbers

With everything pointing to a bigger interest in blogs than a few outliers on our part, there is also another trend we noticed this year: an unprecedented interest in how many ‘hits’ an article got, usually coming from institutions rather than the authors. This interest is expected. At a time when academics have all the more demands put on them, numbers help assess whether blogging is worth the effort. Others enquire more generally about the site’s traffic, to decide not whether to blog but who to blog for. This tends to place university-based blogs in an unfavourable light compared to others with bigger teams and funds – despite the many advantages university blogs offer – while it also makes life difficult for newer blogs.

But is this focus on hits productive in the first place? Using numbers alone to evaluate blogging is misguided: if anything, pieces that get much more attention than others could be doing so because they are controversial, rather than solely because the research is being appreciated. And there is a long-term danger to the quality of content if academic blogging becomes primarily a game of numbers. If an editor’s mission becomes to have competitive totals to report, they would be actively looking for those (usually polemic) pieces that will ‘go viral’ and do the trick each month. That’s when direct advocacy could be prioritised over evidence, that’s when clickbait titles could become more common, and that’s when the lines between academic blogs and other outlets will become blurred.

Putting hits into context

So, other than the number of times a blog gets read, there are other things that matter as well.

A more diverse audience within academia: One of the key strengths of multi-author blogs is that they are read by academics from different disciplines, creating links between the various specialisms. This is an outcome that would not have been facilitated (especially on a daily basis) but for blogs, given research is often published in discipline-specific outlets, or presented in discipline-specific conferences.

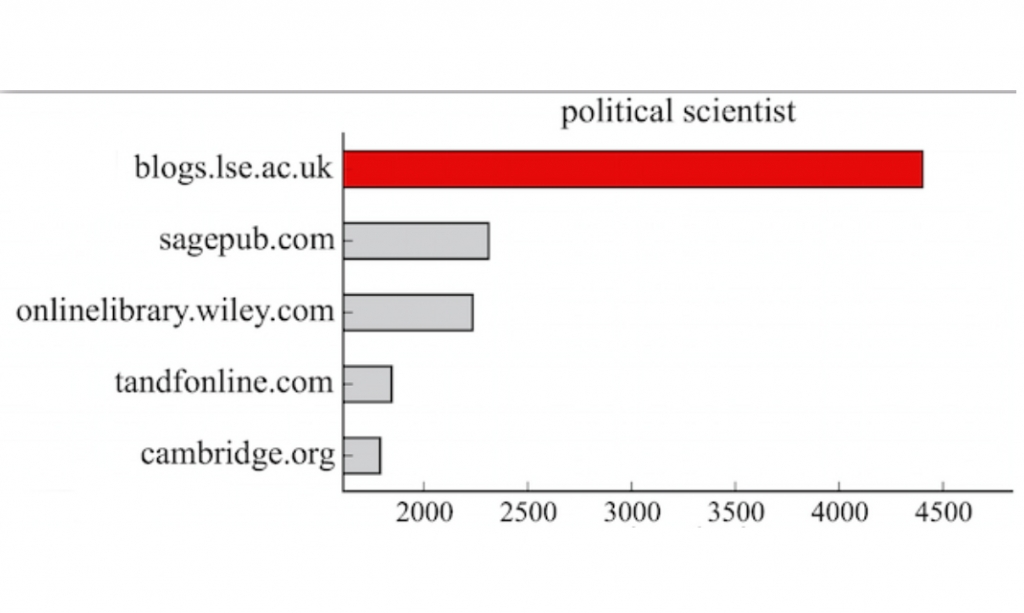

The below figures are from a recent analysis of the domains that scientists share the most on Twitter, and go some way in supporting this point about cross-disciplinary exposure.

Top scientific domains shared on Twitter by disciplines

Source: A systematic identification and analysis of scientists on Twitter, Plos One

Source: A systematic identification and analysis of scientists on Twitter, Plos One

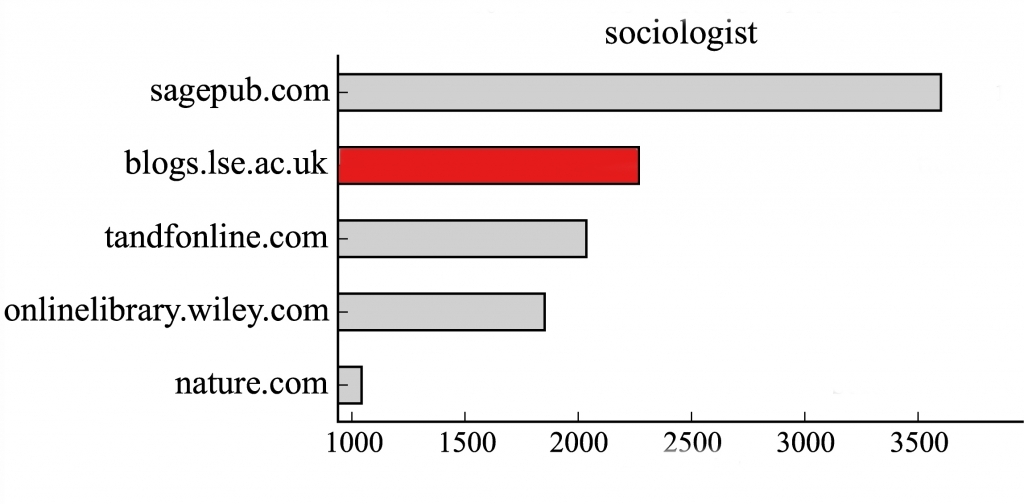

Reaching ‘the public’ at once: Of the 300+ articles we published in 2017, most were summarising research from subscription-only journals; others were drawing on book chapters; and others on conference papers. Few researchers outside of academia, and few policy-makers whose work can be informed by academic research would have learnt about that work if it wasn’t for those blogs. The same goes for journalists and for members of the public who want to be informed. Put simply, the ‘wider audience’ academics are told to reach out to is neither static nor uniform and yet, regardless of its many layers of expertise and interest, can be reached effectively through blogs.

Source: LSE Impact of LSE blogs project

Source: LSE Impact of LSE blogs project

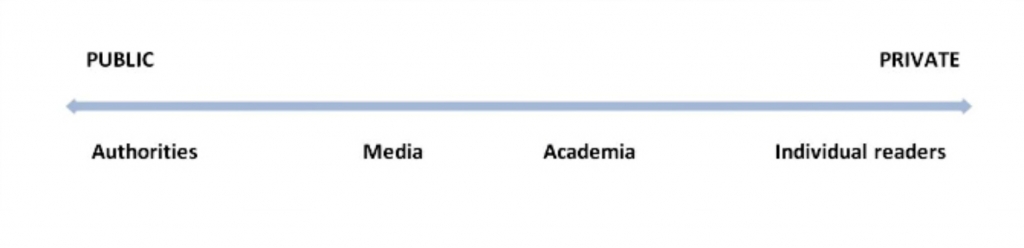

Location: And all of the above is not confined to one country. Much of a blog’s traffic relies on social media, if our own experience mirrors others’ – a third of our traffic comes from Twitter and Facebook. This online amplification means that, unlike other forms of publishing, blogs will certainly be read beyond the author’s own country. Ours is not the greatest example of geographical diversity since articles must have a British politics dimension, yet a good chunk of our readership still comes from outside the UK.

British Politics and Policy blog sessions for part of 2017 by country

Put all the above together and the bigger picture is that, other than the hits an article gets, who makes those hits, what they are looking for, and how they plan to use the information matters a great deal, often more than the sum.

Utilising the ‘two for one’ approach

Perhaps one of the reasons blogging has become so popular is that you don’t have to choose to blog over getting published in other ways. A newspaper article, for instance, will be half the length of a standard blog, so a more elaborate version could be published as a blog, with credit to the newspaper. And very often we do receive such longer versions because the hard-boiled ones had key arguments cut out, and the authors were anxious to address them.

And, of course, neither should academics have to choose between blogging and peer review. Academic blogging is at its best when summarising research that has been published – that’s the niche of academic blogs and the area on which they can capitalise. Journals and publishers too now see value in this process, and over the past six months we started collaborating with some, which is encouraging. This is because a good proportion of those who read blogs will then visit the publication it draws on, benefitting those outlets as a result, especially if they have open access versions.

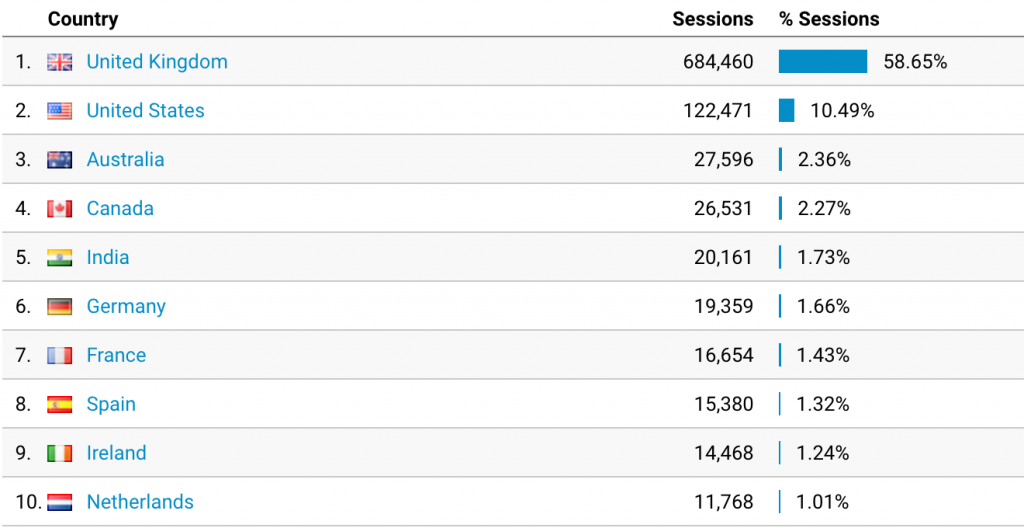

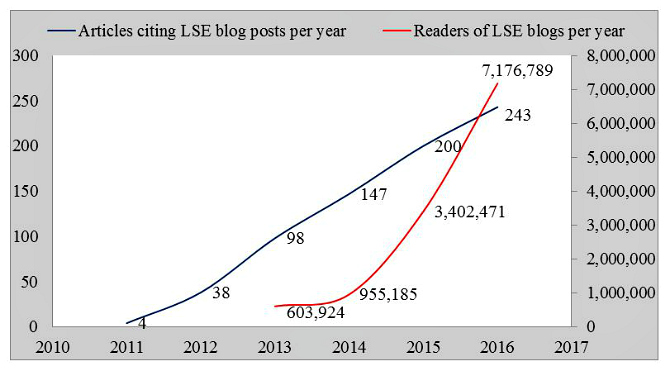

Along similar lines, a conference paper that’s not meant for submission to a journal but much time has been spent on it to go to waste could be turned into a blog, again without deviating a great deal from an academic’s research time. With evidence showing that the number of LSE blogs being cited is on the rise, blogging such a piece could indeed be good news, considering it may never have seen the light of day otherwise.

Growth in readership of and citations to LSE blogs, 2011-2016

Source: Carlos Arrebola using Scopus and Google Analytics data, LSE Impact

Source: Carlos Arrebola using Scopus and Google Analytics data, LSE Impact

Blogging is still defining itself as a genre and much of the process involves trial and error. The good news is that it is not turning out to be an either/or situation: you can blog while publishing in the traditional ways expected of academics, while also writing for mainstream media. With blogs here to stay, there is huge potential for all involved – readers, contributors, publishers, and universities. All these go well beyond just the number of hits.

__________

About the Author

Artemis Photiadou is the Managing Editor of LSE British Politics and Policy. She has previously worked at Full Fact and is currently working towards a PhD in LSE’s International History Department.

Artemis Photiadou is the Managing Editor of LSE British Politics and Policy. She has previously worked at Full Fact and is currently working towards a PhD in LSE’s International History Department.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Featured image credit: Pixabay/Public Domain.