Throughout the AV referendum campaign, there was general agreement that it was a ‘once-in-a-generation’ opportunity for electoral reform in Britain. But, does greater impetus for electoral reform happen only once in a generation? Stuart Wilks-Heeg, of Democratic Audit, investigates the history of proposals to replace our current First Past the Post system, and finds that the shifting balance of power between parties on the left created possibilities for reform in previous decades. If Labour and the Liberal Democrats are able to find common ground on this issue in the coming years, then electoral reform will remain firmly on the table.

Throughout the AV referendum campaign, there was general agreement that it was a ‘once-in-a-generation’ opportunity for electoral reform in Britain. But, does greater impetus for electoral reform happen only once in a generation? Stuart Wilks-Heeg, of Democratic Audit, investigates the history of proposals to replace our current First Past the Post system, and finds that the shifting balance of power between parties on the left created possibilities for reform in previous decades. If Labour and the Liberal Democrats are able to find common ground on this issue in the coming years, then electoral reform will remain firmly on the table.

It is widely held that a defeat for the ‘Yes’ campaign in the Alternative Vote (AV) referendum means that there will be no further opportunity for electoral reform for a generation or more. Like so much of what has been said in the run-up to the referendum, it is difficult to know what this claim is based on – although it is also perhaps the one thing on which the rival campaigns have found common ground.

What is certainly true is that the electorate’s rejection of AV is in fact the fifth occasion in the last 100 years that a high-level proposal to replace FPTP has failed. In every instance, the reform being proposed was either AV or a mixed system, with AV at its heart.

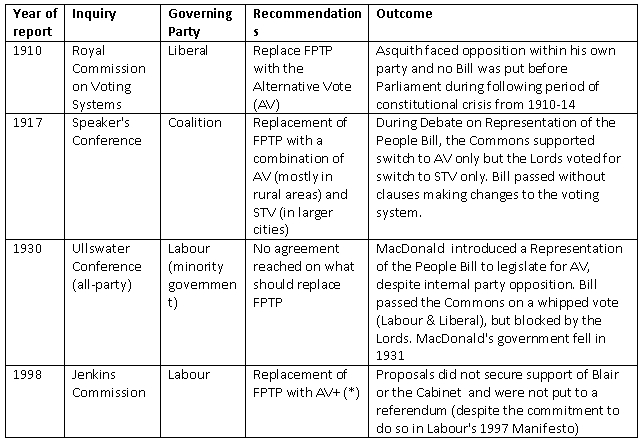

In 1917 and 1930, Bills which included provisions for reform of the electoral system were put before Parliament. As Table 1 below highlights, AV could have been introduced in either instance, but for stand-offs between the House and Commons and the House of Lords. In both 1910 and 1998, official inquires sanctioned by the Prime Minister of the day recommended reform. In 1910, a Royal Commission recommended the adoption of AV, while the Jenkins Commission (PDF) of 1998 advocated a hybrid of AV and proportional representation. In both instances, the governing party underwent a change of heart and decided to stick with the status quo.

Table 1: Official inquires recommending electoral reform in the UK and their outcomes

*Note: AV+ would have been a mixed system, combing constituency MPs elected via AV and regional list MPs elected via proportional representation.

While five attempts in one hundred years does translate into a rough average of ‘once a generation’, it is also evident that the UK’s brushes with electoral reform have been clustered into two distinct periods – one from 1906-31 and another from 1997 onwards. The reason for this pattern, and for the persistent failure to bring about reform, is not especially hard to identify. It is the interaction between the electoral system and changes in the party system which serves both to promote the possibility of reform and to prevent it.

It is not simply that FPTP artificially reproduces the dominance of two parties, who therefore have no interest in reforming it. The party system, and the calculus of who supports or opposes reform, is in fact far more fluid . As Figure 1 below shows, the non two-party vote has fluctuated between 5 and 35 per cent since 1900. Over this period, the status of ‘third party’, as measured by share of the vote, switched from Labour to the Liberals in 1922, while in 1983 and 2010 the gap in electoral support between, respectively, Labour and the Alliance, and Labour and the Liberal Democrats narrowed dramatically.

Figure 1: Changes in the non two-party vote, 1900-2010

It was this shifting balance between the two parties of the centre left which created the previous opportunities for reform in 1910, 1917, 1930 and 1998. Yet, possible Lib-Lab coalitions of interest to bring about reform have tended, in each instance, to prove short-lived. Indeed, the history of failure to secure electoral reform hinges on the ever-changing political calculus between Labour and the Liberal/Liberal Democrats.

Prior to 1918, it was Labour who advocated reform – a position which they rapidly moderated after it became clear that they had displaced the Liberals as the second force in British politics during the 1920s. By 1929, the policy positions of Labour and the Liberals on electoral reform had been reversed, but so too had their respective standings in the party system. In 1998, the calculus was different again. Having secured a landslide victory, Blair’s pre-election agreement with the Liberal Democrats to hold a referendum on electoral reform, agreed as a ‘plan B’ in the event of a ‘hung Parliament’, was quietly forgotten.

Arguably, the events of 2011 will come to fit the same pattern – despite the fact that the referendum notionally took the decision out of the hands of the political parties and that it arose from the coalition agreement between the Conservatives and the Liberal Democrats. Indeed, two of the most striking aspects of the referendum are, first, the extent to which it has been dominated by party politics and, second, the failure to secure a solid Lib-Lab alignment in favour of change.

History suggests that only a prolonged return to the two-party politics of 1931-70 will take electoral reform off the agenda for a generation or more. Despite the catastrophic performance of the Liberal Democrats in last week’s elections, such a scenario is almost unthinkable. The real question for the next 20 years is whether Labour, the Liberal Democrats and others can find common ground on electoral reform – only then will history stop repeating itself.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Electoral reform will come again because FPTP doesn’t work in a multiparty democracy.

Next time we should follow the New Zealand example. The referendum question should be a non binding question, simply, ‘Should we change the voting system?’

There would be a much better chance of getting a YES result, because the referendum debate would be all about FPTP, which is difficult to defend.

With a YES vote, in even a nonbinding referendum, we would be on the road to PR. We should then choose a system akin to AMS, preserving the single member constituency and simple voting and counting. We should abandon preferential systems such as STV.

For an ‘AMS’ type PR system that avoids the problems inherent in party lists, where all MPs are constituency MPs, google ‘DPR Voting’