Alex Yeandle examines the geographically delimited roll out of BBC radio in England, which coincided with successive off-cycle general elections in the 1920s. He finds that the construction of a radio transmitter is associated with a 2% yearly increase in voter turnout at the constituency level.

‘This is 2LO, Marconi House, London calling’. On 14 November 1922, these words marked the beginning of BBC radio, a point at which mass media in Britain changed forever. The services we all know today, from listening to the six o’clock news through to watching Line of Duty on the iPlayer, all stem from decisions made by entrepreneurs, and a reluctant Post Office, more than a century ago.

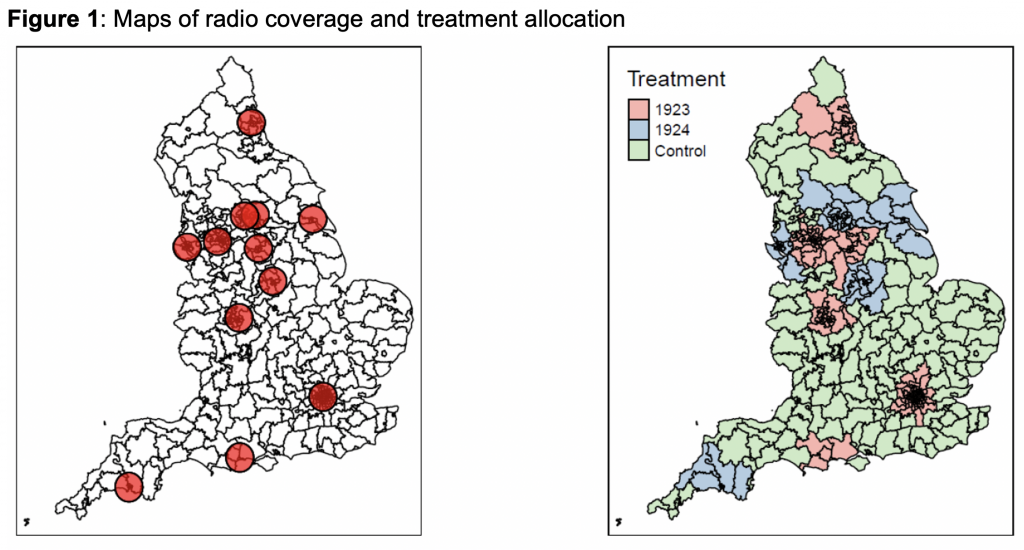

The radio service began in London but spread quickly across the country. Transmitters were erected at pace in towns and cities, from Birmingham to Bournemouth to Bradford, and within four years more than 70% of the population lived within listening range of a station. As is common, the new service was rolled out to different parts of the country at different times. But these differences stemmed from technical considerations, like which places had the most people or the more suitable topography, rather than the government trying to reward its own supporters.

The new radio service offered a striking change for British voters at the time. In the 1920s many were illiterate, unable to benefit from advances in the printed press. Those who could read were constrained by newspapers that had become increasingly focused on entertainment, rather than informative reporting. For the millions of working class and female voters added to the electoral roll in post-war changes to the franchise, an informative and impartial radio service allowed them to navigate a complex political environment for the very first time. The service was also used to construct a form of British national identity that emphasised civic engagement, in an attempt to bring a fractured country together after the war.

While the history of the BBC is well documented, as is its role in constructing many facets of national identity that persist to this day, we still know very little about its shorter term effects. In particular, scholars have not considered whether the rollout had any systematic effects on voters in the 1920s, where several hung parliaments, the collapse of the Liberals, and the first Labour government all occurred within a few short years.

In new research I seek to fill this gap. Building on existing literature on political participation, which emphasises the importance of political information and civic duty, I theorise that the advent of BBC radio increased voter turnout in Britain. When political participation is difficult and politics itself uncertain, a profound shift in media technology has the potential to reshape the electorate’s engagement with the democratic process. In this vein, I argue that the rollout of BBC radio is a neglected contributory factor to Britain’s rising political participation throughout the 1920s, which saw its development to something far more akin to the ‘free and fair’ democracy we have today.

Measuring social phenomena from a century ago is no doubt challenging, but the paper makes use of a few historical conveniences. The first is that, thanks to the BBC’s official historian Asa Briggs and former chief engineer Edward Pawley, there is detailed archival data about where and when radio transmitters were constructed around the country. This allowed me to digitise which voters were living within coverage range of the radio, and the specific time at which their coverage began. The second is that British politics in the 1920s was in a tremendous state of flux, with multiple off-cycle elections being triggered by opportunistic Prime Ministers and unstable hung parliaments. In addition to a baseline post-war election in 1918, further plebiscites took place in 1922, 1923, and 1924, perfectly cross-cutting the rollout of the radio. This allowed me to create a panel dataset, in which each electoral constituency is observed multiple times, and, crucially, in which different constituencies receive radio coverage at different times. With this data, I could isolate the specific effect of radio coverage from other general trends that were affecting the country in this period.

When doing this analysis, I find that the construction of a radio transmitter is associated with a 2% yearly increase in voter turnout at the constituency level. This is a significant result, given the close nature of many individual seats, and indeed the overall composition of parliament at the time. Many parliamentarians may well have won or lost seats because of changing participation rates, and this may have contributed to Liberals’ demise as a key player in Britain’s two-party system.

To make sure that the findings are robust, I draw on the 1921 census, a rich source of data about the people living in each constituency, and match similar constituencies with one another. This ensures that the most similar parts of the country are being compared, so that the estimates are more reliable. I re-run the core analyses with radio coverage measured in several different ways and with thousands of artificial, simulated rollouts, showing that positive effects on turnout are consistent and arise only from the actual distribution of radio coverage that took place. I also account for the behaviour of voters in neighbouring constituencies, ensuring that turnout is not being driven upwards by people travelling for work, or by politicians campaigning across constituency borders. The finding that radio coverage is associated with increased voter turnout persists across each of these tests.

Existing scholarship on 1920s British politics stresses the importance of expanded suffrage and a rising Labour Party. Both of these factors are crucial, and clearly had dramatic effects on the political landscape of the era. This new research, however, stresses the role played by technological change, showing that a rapid change in how voters learn about politics can have consequences for their behaviour at the ballot box.

Do these new findings tell us anything about contemporary politics? In fact, the dynamics of the radio service share similarities to those observed by social scientists around the world. Be it television rollouts across Latin America in the 1970s, the expansion of mobile telephony in Sub-Saharan Africa in the late 2000s, or rising exposure to social media and ‘fake news’ across the world, there is plenty of evidence that media shocks can have profound effects on voting behaviour, particularly where democracies are younger and politics less certain. Indeed, a hundred years later in modern Britain, scholars have studied the rollout of high-speed broadband, finding marked effects on voter turnout as voters replace informative news with entertainment-oriented online content. So, while the research presented here is deeply contextual, it no doubt describes a broader phenomenon taking place in societies across time and space.

In the words of its first Director General, John Reith, the initial aim of the BBC was to ‘inform, educate and entertain’, creating a ‘more enlightened and intelligent electorate’ in the process. Based on its immediate effects on political participation, and its continued dominance a century later, Reith’s lofty ambitions appear to have been met with considerable success. By closely studying its effects at a particular historical juncture, I hope to further our understanding of the world’s oldest public broadcaster going forward.

_______________________

Note: the above draws on the author’s published work in Electoral Studies.

Alex Yeandle is an MRes/PhD student in Political Science at the LSE.

Photo by Alessandro Cerino on Unsplash.