In many countries, members of parliament receive publicly funded allowances to communicate with the electorate. Some hope that such communication engages people with politics and increases electoral participation. Others worry that such use of public funds creates an unfair advantage for incumbents. Data from the UK suggests that both the hopes and the worries around such allowances are baseless, writes Resul Umit.

In many countries, members of parliament receive publicly funded allowances to communicate with the electorate. Some hope that such communication engages people with politics and increases electoral participation. Others worry that such use of public funds creates an unfair advantage for incumbents. Data from the UK suggests that both the hopes and the worries around such allowances are baseless, writes Resul Umit.

In 2007, the House of Commons established a new Communications Allowance for members of parliament to cover the cost of communication with their constituents about parliamentary affairs. This was to help engage the public with politics and, for example, increase electoral turnout.

Not everyone was convinced. The Conservatives voted against the allowance while Labour voted in favour of it. The Liberal Democrats were divided. Among the arguments against the allowance was the worry that it would be used for political purposes, giving an unfair electoral advantage to incumbents. Before long, and amid the scandal around the parliamentary expenses in general, the House of Commons abolished the allowance in 2010. In the meantime, MPs spent £13.8m to communicate with their constituents.

So, did the Communications Allowance increase electoral turnout? Did it bring electoral benefits to the incumbents? In a recently published article, I look for answers to these questions. The results suggest that it did neither.

Communications Allowance

MPs have long had free stationery and postage-paid envelopes, but these had to be used only for solicited communication with individual constituents. With the Communications Allowance, they could communicate with all constituents proactively, through various channels.

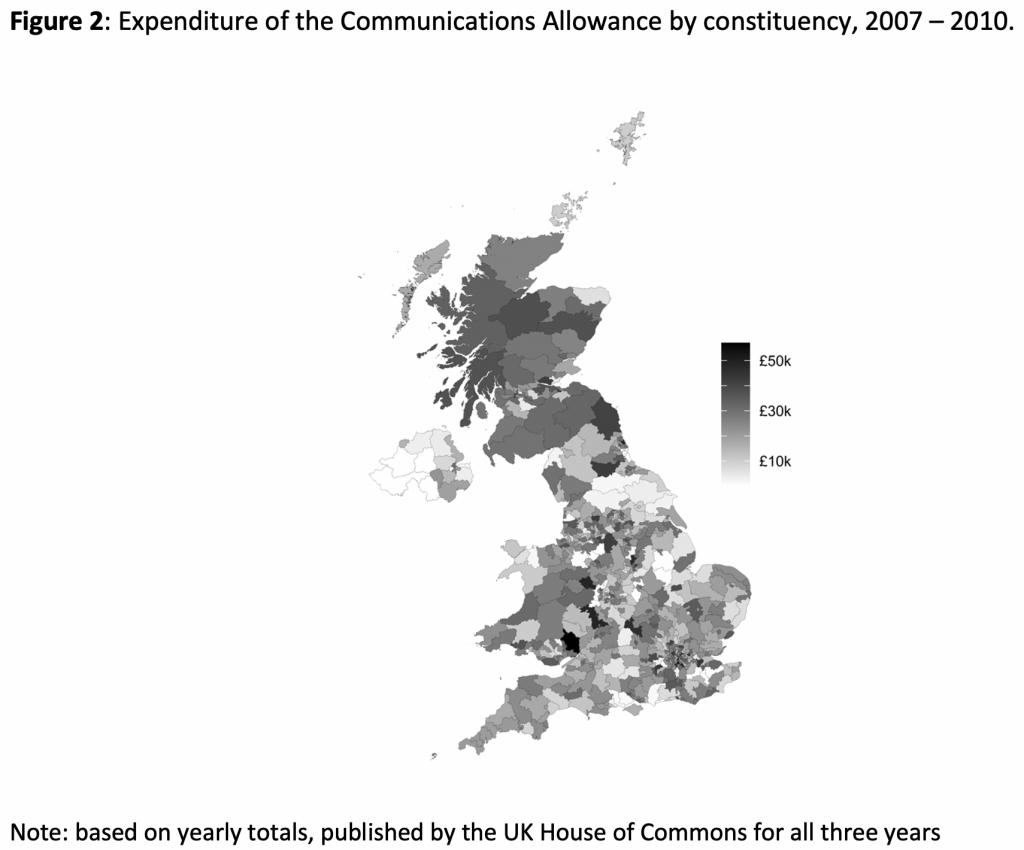

Figure 1 suggests that publications were the most popular channel as the lion’s share was spent on producing and delivering publications such as newsletters. The volume of such publications was so great that many MPs invested in equipment like paper folder and inserters, a closer look at the receipts reveals. MPs also used their allowance to advertise their contact and surgery details and set up websites.

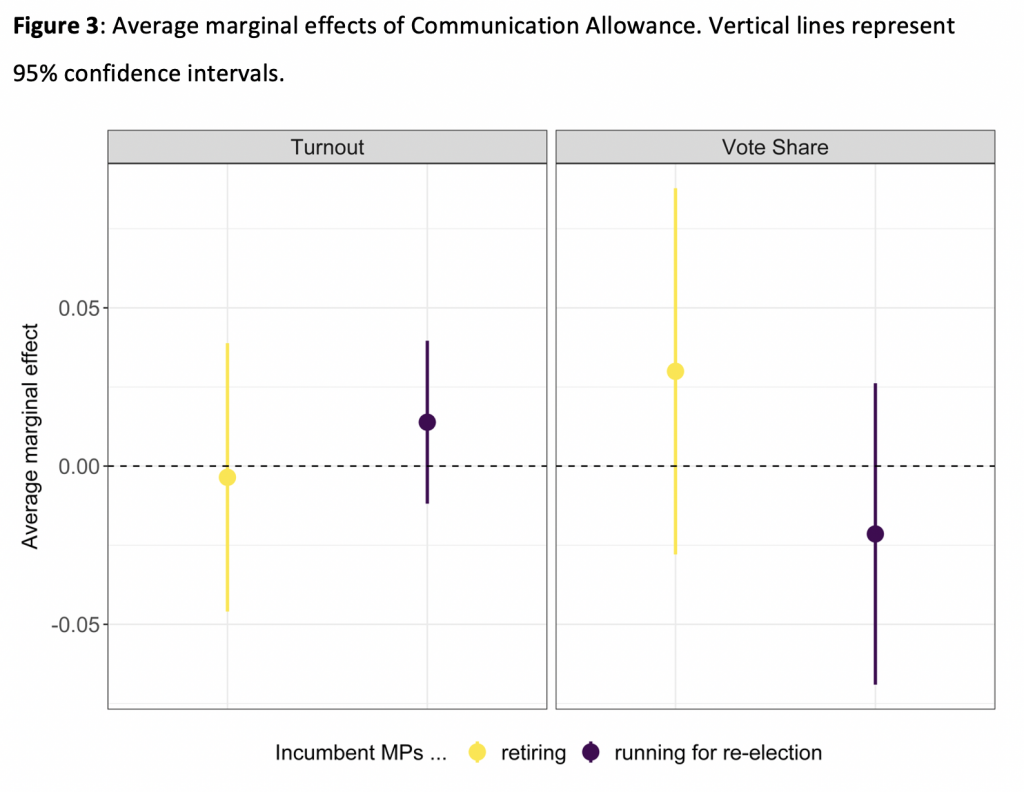

The allowance was set at £10,000 for the 2007–2008 parliamentary year, raised to £10,400 for the following two years. MPs could surpass these limits by transferring funds from other allowances into the Communications Allowance. Indeed, as Figure 2 shows, many did so—some MPs spent over £57,000 for parliamentary communication in three years.

The allowance was set at £10,000 for the 2007–2008 parliamentary year, raised to £10,400 for the following two years. MPs could surpass these limits by transferring funds from other allowances into the Communications Allowance. Indeed, as Figure 2 shows, many did so—some MPs spent over £57,000 for parliamentary communication in three years.

Others claimed much less, or nothing. Hence, the key question is whether there was a parallel variation in electoral outcomes at the end of the allowance period, in the 2010 UK general election — given a number of observable characteristics, such as the baseline turnout and vote shares in the preceding election.

Results

The results suggest that if there was a relationship between how much was spent on communication and how many people turned out to vote, it is substantively and statistically an insignificant relationship.

The best estimate is that the average constituency, upon receiving £21,300 worth of communication, saw about a 0.2 percentage point increase in turnout. In other words, if MPs were to spend all of their allowance of around £10,000 per year, consistently for three years between the two elections, this increase would be less than half a percentage point—a change that is likely to go unnoticed after rounding.

The results from vote shares are similar. Accordingly, where MPs spent £10,000 for parliamentary communication, their party saw a change ranging between a 0.39 percentage point decrease to a 0.37 percentage point increase in their vote share in the UK 2010 general election.

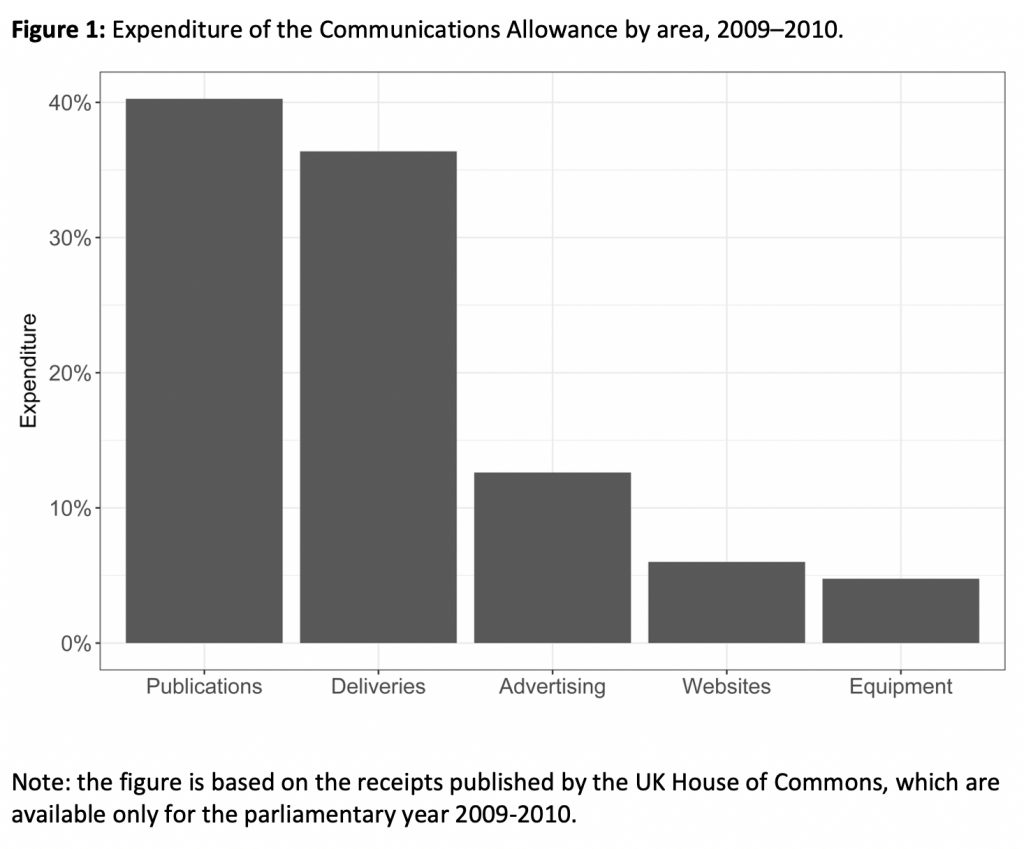

A high number of MPs chose not to seek re-election in 2010. Would the results look different if we did not pool all electoral races, with and without an incumbent candidate, together? Figure 3 suggests not, for both groups and outcomes: the average communication effort can have a small, positive or negative, effect on the results but they can as well have no effect at all — and the incumbents’ presence among the candidates seeking re-election does not change this fact.

Additional tests suggest that these results are not sensitive to the level of analysis or choice of outcomes measures above. In other words, the null results from constituency level analysis of turnout and vote share replicate in constituent level analysis of five additional outcome measures. Specifically, respondents living in constituencies with higher communication expenditures did not think that their MP was working any harder, compared to respondents living in constituencies with lower expenditures. Similarly, there were no meaningful differences between the two groups in terms of trust in parliament, electoral interest, political attention, or satisfaction with democracy.

Implications

In many countries, MPs receive publicly funded allowances to communicate with the electorate. The null results above are good as well as bad news for actors looking to engage the public with politics through parliamentary communication.

On the one hand, they are bad news as communication allowances seem ineffective in terms of desirable indicators, such as increases in electoral turnout. If this is indeed the case, it would be harder for policymakers to justify the money and effort that goes into parliamentary communication.

On the other hand, the results are good news as communication allowances do not seem to give incumbents an unfair advantage through public funds. Hence parliaments can push back on the claim that communication allowances distort the will of the people. This might, however, lead to another problem: parliaments might find it harder to encourage MPs to spend their time and effort, if not their own money, for parliamentary communication if there is no electoral incentive for them to do so.

______________________

Note: the above draws on the author’s published work in Political Studies Review.

Resul Umit (@ResulUmit) is a post-doctoral researcher at the ARENA Centre for European Studies, University of Oslo.

Resul Umit (@ResulUmit) is a post-doctoral researcher at the ARENA Centre for European Studies, University of Oslo.

Photo by Pawan Kawan on Unsplash.