The official, substantially verbatim report of what is said in Parliament is an essential tool for ensuring democratic accountability. This record, Hansard, contains a wealth of data, but it is not always fully accessible and easy to search. Lesley Jeffries and Fransina de Jager explain how a new project, Hansard at Huddersfield, aims to improve access to the Hansard records and contribute new ways of searching the data.

The official, substantially verbatim report of what is said in Parliament is an essential tool for ensuring democratic accountability. This record, Hansard, contains a wealth of data, but it is not always fully accessible and easy to search. Lesley Jeffries and Fransina de Jager explain how a new project, Hansard at Huddersfield, aims to improve access to the Hansard records and contribute new ways of searching the data.

A correctly functioning representative democracy, where the people are the ultimate source of political power, requires openness from Parliament and active participation from the public. To hold their leaders accountable, the public needs to know what is being said and done in parliamentary debate. Such transparency can be achieved through the societal watchdog, journalism. From the early 1800s onwards, newspapers devoted full pages to parliamentary reports, and in the early days, parliamentary records, known as Hansard, were sourced from these newspaper accounts. In the early 20th century Hansard was brought into parliament itself with the remit of producing comprehensive and unbiased records of what is said in the Palace of Westminster. In the early 1990s, when Parliament allowed live broadcasts of debates, newspapers largely discontinued their direct parliamentary report, but Hansard continued its work of recording all official business in both houses of Parliament. This priceless resource has the capacity to be searched electronically more easily than video data, and has been available online since 1997, with a new integrated website (hansard.parliament.uk) launched in 2018.

Hansard as a democratic resource

Despite the very many ways in which citizens can now access parliamentary debate directly (via television, Youtube, SoundCloud, social media and so on), Hansard still provides the most comprehensive and democratic access to the language of government and Parliament. Edited only for repetitions and obvious mistakes, and without altering the meaning of what was said, Hansard reports full parliamentary debates, parliamentary decisions and votes for both houses of Parliament. Because Hansard has records of parliamentary debates since 1803, the public can use it to keep up with the progress of politics as well as learning about ways in which Parliament has dealt with societal issues over time. Audio-visual recordings of parliamentary debate do not go as far back nor provide for easy searching.

Is it really democratic?

Theoretically, Hansard should thus be democratically accessible to all citizens. In the past, the printed version of Hansard had to be paid for. Hansard first became available online for free in 1997 when parliament launched its website. Since then the online version of Hansard has evolved in its efforts to make Hansard available to everyone and keep up with the technological developments. The Hansard Story, a short history of Hansard, puts it like this: ‘[Hansard] responds to democratic need, offering a service that spans past and present, with a watchful eye on the future,’ (p.51).

In 2018, Hansard launched a website that combined Historic Hansard (1803–2005) with the contemporary record. Nevertheless, the basic search functions of the site remain linked to the structure of Hansard’s data, so that while searching for particular debates or people may be easy, searching for a topic over a period of time, for example, or even searching by the party membership of speakers, is tricky.

How Hansard at Huddersfield can improve democratic access

Our project, Hansard at Huddersfield, based at the University at Huddersfield, uses new ways of searching and presenting data, influenced by methods in corpus linguistics, in order to stimulate interest in, and use of, the Hansard records. The aim is to create a website that responds to what the public wants to know, and which eases the search process to help people find features and patterns of parliamentary speech that may inform their professional or personal concerns. With a team of linguists and computer scientists on board, the project has simplified linguistic methods for searching large datasets to create an easily searchable website that provides clearly visualised results from complex searches.

In order to make the website more democratic (within our time and means), Hansard at Huddersfield has collaborated with potential users of the site to identify their areas of interest in exploring Hansard. We discovered that their main interest in searching Hansard was to find key themes and patterns in debates over a certain period of time and if possible to be in a position to compare their findings across parties, timescales and other parameters. To help them interpret their findings, they wanted contextual information such as who spoke, or which party they belong to.

Although there is a range of software available to search large datasets to answer such questions, for non-expert users this software demands too much knowledge of linguistics and statistics to warrant easy interpretation of the findings. By simplifying these methods, however, we hope that end-users without such specialised knowledge will be able to access the data in previously unavailable ways, and be able to explore the data in a range of intuitive methods. Hansard at Huddersfield introduces interactive diagrammatic representations to visualise the findings. Whilst these visualisations are both attractive and informative, we have also made certain that the user can always access the original Hansard entries to ensure that there is complete transparency in the use of the data.

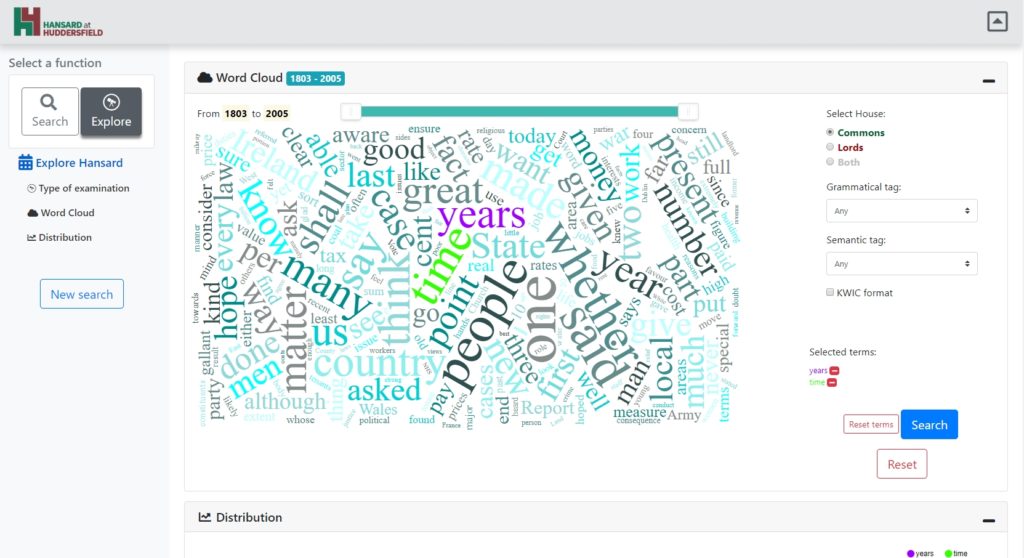

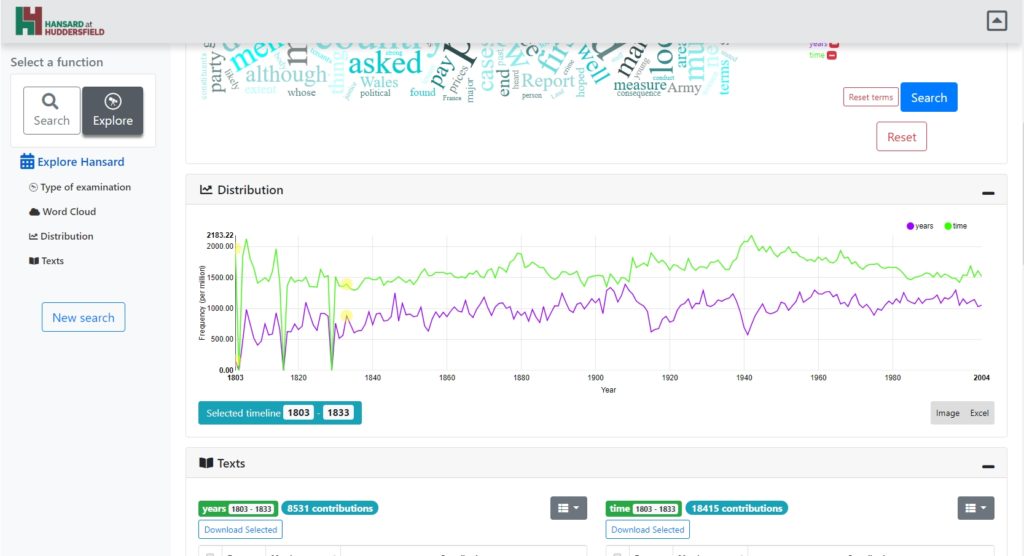

As an example, on our site you can explore the Hansard data without a pre-determined search term, such as through a word cloud (see Figure 1). From this, you can select a few words to see their frequency distribution over time (Figure 2), and a list of all the contributions that feature the selected words in that time period. From this list you can select single contributions that can be explored separately.

Figure 1: Word cloud from Hansard at Huddersfield

Figure 2: Frequency distribution of two words in Hansard over time

While the Hansard at Huddersfield website presents more ways to explore Hansard, it is still not close to being maximally accessible to everyone or relevant for all possible research needs. The one-year time period of the project meant there were limits to its ambition, but we aim to continue developing the site for another nine months. We hope that its main achievement will be to inspire users of Hansard to explore this incredibly rich resource in new and imaginative ways and to encourage the public to engage with Hansard directly, unmediated by journalism. Hansard at Huddersfield aspires to influence the way that the voting public uses Hansard in their role of keeping government accountable. If so, we dare to hope that our new interface for this valuable data will, in some modest way, enhance the public’s engagement with democracy.

______________

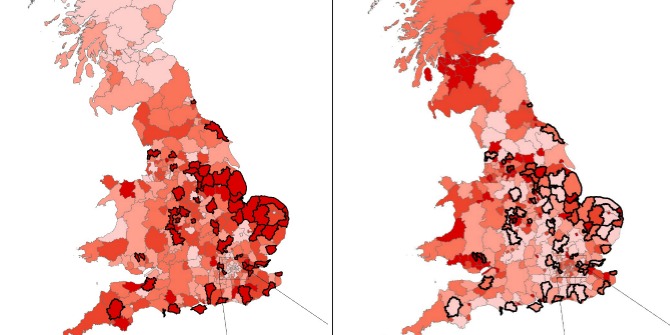

Note: The above was first published on Democratic Audit. Hansard in Huddersfield is funded by the AHRC (AH/R007136/1). Image credit: UK Parliament, via Parliamentary Copyright.

Lesley Jeffries is Professor of English Language at the University of Huddersfield and Principal Investigator on the Hansard at Huddersfield project.

Lesley Jeffries is Professor of English Language at the University of Huddersfield and Principal Investigator on the Hansard at Huddersfield project.

Fransina de Jager is a PhD student in Linguistics at the University of Huddersfield and research assistant on the Hansard at Huddersfield project.

Fransina de Jager is a PhD student in Linguistics at the University of Huddersfield and research assistant on the Hansard at Huddersfield project.

I’d argue that there is a largely false premise here. Representative Democracy and a very active ‘polis’ are not necessarily mutually supportive. https://link.medium.com/H3yaOmi7XU