This year’s ill-fated AV referendum showed that most of the UK population were not in favour of supporting what experts called a fairer voting system. In his review of Electronic Elections, Charles Crawford learns about the fraud, mischief and incompetence in various voting systems that can intrude to stop voters’ votes being registered accurately.

This year’s ill-fated AV referendum showed that most of the UK population were not in favour of supporting what experts called a fairer voting system. In his review of Electronic Elections, Charles Crawford learns about the fraud, mischief and incompetence in various voting systems that can intrude to stop voters’ votes being registered accurately.

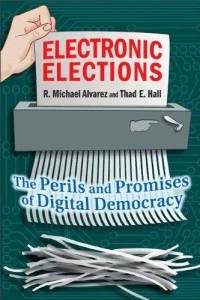

Electronic Elections: The Perils and Promises of Digital Democracy. R. Michael Alvarez and Thad E. Hall. Princeton University Press.

In this book professors Michael Alvarez (California Institute of Technology) and Thad Hall (University of Utah) skilfully look at the pros and cons of different arrangements for people voting in public elections. It richly deserves to be read by anyone interested either in the theory of democracy or in how government attaches itself to real life.

As the ill-fated voting system referendum earlier this year showed, we in the UK don’t like to be bothered by experts telling us that our first-past-the-post voting system is inefficient or unfair. Everyone understands putting a cross on a piece of paper next to one’s favourite candidate and adding up the results. If it’s not broke, why fix it?

This book shows us that such comfy thinking rests on subtle but not necessarily accurate assumptions. At every stage of the voting process (and there are many of them) fraud, mischief or incompetence can intrude to stop voters’ votes being registered accurately.

Over in the USA disagreements over voting arrangements are much more pronounced. States’ voting systems have evolved for historical reasons: states don’t want a one-size-fits-all system imposed by Washington. This has a democratic quality of its own, but it lead to anomalies.

A highpoint of public interest in voting as such came in 2000 when hanging chads in Florida helped decide the winner of the nationwide presidential election race. This controversy boosted those arguing for electronic voting. But since then the mood has changed: voters are worried about opportunities for abuse with a pure electronic voting system.

The book examines the party political resonance of arguments about US voting systems. Republicans tend to favour robust arrangements for checking that people voting are indeed entitled to vote, and that (for example) voters should produce an identity document. Democrats tend to argue that such formalities can in fact work against the poorest citizens. The authors point to the underlying philosophical trade-offs between efficiency and fairness.

A basic principle of democracy (note: the book helpfully reminds us that it has not always been this way) is secret voting – no-one can trace how any one voter voted. Electronic transactions in shops and online purchases work only because they link transactions to a specific person. Can any online voting system rule out fraud and retain substantive anonymity? The authors praise work done in the UK and other European countries to look at these issues in a systematic way.

The heart of the book is the authors’ emphasis on sensible risk analysis. Above all, they punch on the nose the odious “precautionary principle” – the superficially appealing but in fact spurious idea that nothing new should be accepted unless it can be proved to do no harm.

The authors do a fine job in insisting that it makes no sense to apply that argument to proposed reforms while not applying it to the current state of affairs too. In other words, those who object to (say) electronic voting on the grounds that it increases the risk of abuse need to compare those supposed risks with the actual risks of abuse in the current system. Advantages of electronic voting likewise need to be given fair wind: research shows (they say) that electronic voting systems reduce ambiguous or “spoilt “votes, thereby increasing effective participation rates and (arguably) the legitimacy of the result.

The book also looks at the cost of elections. Classic paper-based voting arrangements are labour-intensive and expensive. Electronic voting cuts costs significantly once the system is set up and reduces the risk of human error. What price democracy?

The book concludes with recommendations for looking at voting system reform in the USA, and hopes for “a thoughtful, fact-based, rational discussion …of election administration and voting technology”. Given the very complexity of the policy and philosophical issues this book itself describes, this is a forlorn hope.

My main concern is that the book does not do justice to what I would call the “law of large numbers”. The very fact that old-fashioned voting systems are so labour-intensive means that it is almost impossible to cheat on a scale that matters without that cheating being obvious. The supreme risk of electronic voting is that those who program the system or malevolent hackers can infiltrate it secretly to influence the outcome. Such abuse need not involve crudely forcing a victory for one party or the other: it might be enough to “nudge” the results so that over time advantages for one party accumulate.

The book quotes the US National Academies of Science: “Democracies derive their legitimacy from elections that the people collectively can trust”. Are voters ever likely to trust an e-voting procedure which might be systemically distorted without anyone knowing?

Electronic Elections: The Perils and Promises of Digital Democracy. R. Michael Alvarez and Thad E. Hall. Princeton University Press. January 2011.

Find this book: ![]() Google Books

Google Books ![]() Amazon

Amazon ![]() LSE Library

LSE Library

In essence traditional vote works because the process does not happens in a blackbox, and there are many people watching every step in the process. If a electronic process would have he same properties, it would work without cheating as well.

There is project propose a decentralized electronic democracy architecture where anyone can connect his computer to verify the process (P2P democracy!!!), with cascade, multiple, revocable delegation of the vote, continuous round voting, open proposals and amends (anyone can do it) and editable procedures, so that the program that handle the flow of decision can be modified and amended like any other proposal. http://www.frictionfreedemocracy.org/ and https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ujddVQR4BvQ