Stories of Cosmopolitan Belonging brings together work from cutting-edge interdisciplinary scholars researching home, migration and belonging, using their original research to argue for greater attention to how feeling and emotion is deeply embedded in social structures and power relations. This collection of essays immerses the reader in the lives and voices of the fieldwork participants, and in doing so renders itself both a solid intellectual resource and a beautiful collection of insights into the emotional lives shaped by the cosmopolitan city, writes Sarah Burton. In short, this is a collection of essays which deserves to be read far more widely than urban studies; its methodological and theoretical richness is the kind that keeps on giving with every read.

This review was originally published on the LSE Review of Books.

Stories of Cosmopolitan Belonging: Emotion and Location. Hannah Jones and Emma Jackson. Routledge. May 2014.

Stories of Cosmopolitan Belonging: Emotion and Location. Hannah Jones and Emma Jackson. Routledge. May 2014.

With Stories of Cosmopolitan Belonging, Hannah Jones and Emma Jackson have produced the sort of text that a careful reader will return to endlessly. The premise of the collection – to focus on ‘the connections across places and spaces, and their co-constitution through felt relations’ (p.5) – is neatly realised across twelve chapters. These move the reader from inner city London through to Bosnia, Jamaica, and Mexico City, and cover diverse contexts of belonging and change in a cosmopolitan world – urban housing, crime, music, and policy making, to name just a few.

The book opens with two introductory chapters: ‘Moving and Being Moved’ by Jones, Jackson, and Alex Rhys-Taylor; and ‘Reflections: Writing Cities’ by Les Back and Michael Keith. The former grounds the book in ‘the connections between motion and emotion’ (p.2), providing a lucid and fine-grained justification for taking emotion and affect seriously in the study of urban societies. As Jones et al note, ‘underpinning this book is the notion that exploring such uncomfortable emotions and their circulation is essential for understanding social and spatial processes’ (p.2). Further to this, Jones et al introduce the idea that focusing on emotional ties – one’s sense of belonging to a place – can help us to understand how this belonging ‘remakes places as well as people’ (p.5), thus clearly outlining the usefulness of connecting the various themes of cosmopolitanism, urban life, and affect. The latter chapter by Back and Keith asks the question ‘how should we approach the city?’ (p.15) and explores how different ‘vantage points’ may intersect with the ‘research imagination’. Moreover, Back and Keith point to the vitality of the methods used to tell stories of the city and the urban, and how these can fruitfully intersect with recent calls for public sociology. They stress the importance of finding ways ‘to attend to the fleeting and the distributed’ (p.23) and the wider political relevance of this sort of imaginative writing to countering the ‘cultures of audit that are obsessed with paper’ (p.24). Stories of Cosmopolitan Belonging, then, is a text which both tells us things, and in its construction and politics, acts as a quiet call to arms for all social scientists, but urban writers especially.

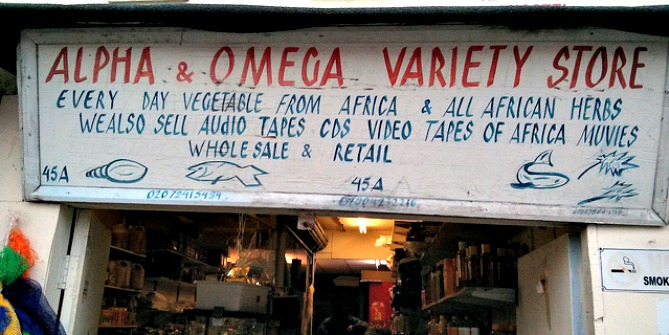

Alex Rhys-Taylor’s chapter ‘Intersemiotic Fruit: mangoes, multiculture and the city’ is an examination of the emotional connection to food and its place in cosmopolitan belonging. Beginning with a survey of the bourgeois excess available across the kitchens and restaurants of London, Rhys-Taylor moves to the specific location of Ridley Road market in Dalston, east London. Through ethnographic study, Rhys-Taylor draws lines across the globe, and between the individuals who frequent the market, demonstrating how different objects – in this case, food – provide different experiences of cultural attachment.

Rhys-Taylor foregrounds the story of Marcia from Saint Lucia who buys mangoes to share with her children and grandchildren, but complains that these are Pakistani mangoes and lack the flavour of her favourite childhood treat. Nevertheless, as Rhys-Taylor notes, they remain ‘evocative of childhood landscapes to which she remains attached’ (p.46). In this regard, Rhys-Taylor indicates how the fruit functions as both ‘dietetic and emotional nutrition’ (p.46). This is not to say that the chapter presents an unproblematic account of the presence of exotic fruit in a Western location, and the subsequent affective relations of migrant communities. Rhys-Taylor acknowledges that ‘the consumption of exotic fruit can become a site for the reiteration of colonial power relations’ but asserts that it also provides ‘points of mutual affection and overlap out of which a convivial metropolitan multiculture can be made’ (p.46). The strength of this chapter is in its able demonstration of the ‘remarkable array of overlap between the “sensory orders” of migrant groups’ (p.51), and the parallel between this and the flow of the berries, fruits, and spices themselves: as Rhys-Taylor succinctly notes, ‘histories of colonial rule seem to partly prefigure the sites for interaction between seemingly discrete traditions, by providing the material culture of post-colonial multiculture’ (p.51).

In this context Anamik Saha and Sophie Watson’s chapter ‘Ambivalent affect/emotion: Conflicted discourses of multicultural belonging’ is especially interesting. Here, Saha and Watson consider the relationships between migrant groups, and question how to approach ‘those difficult and troubling moments of daily feeling that migrants sometimes express towards what they themselves see as the less palatable residues of contemporary multiculture’ (p.99). Through the fascinating reflections of 30-something British South Asians living in the London Borough of Redbridge, Saha and Watson provide insight into the ‘emotion of ambivalence from migrants towards the practices of other migrants’ (p.101). The authors draw attention to the discomfort and embarrassment displayed in participants’ critique of the ‘influx’ of other migrant communities to Redbridge, thus providing an especially nuanced depiction of different forms of belonging and connection to place. Particularly intriguing is how often these 30-something children of ‘original’ migrant communities expressed to Saha and Watson a nostalgia for what the authors refer to as ‘a very particular English past’ (p.106). According to Saha and Watson, participants in the study showed ‘a sentimental longing for a time when the area was more ethnically diverse and multicultural’ (p.107), and connect this with a loss of heritage – particularly in the changing facades of houses. In doing so, participants’ reflections pointed to how ‘emotional attachment to an area is expressed through a perception of how the physical area has changed, which in turn, expresses a certain ideal about multiculturalism and community’ (p.107). This chapter is uncomfortable research at its best and emphasises the need for sociologists to pay attention to the difficult ways that research participants may narrate their experiences, especially when they are discordant with our own intellectual notions of raced, classed, and gendered bodies, places, and spaces.

Stories of Cosmopolitan Belonging is a significant addition to the current work of urban sociology and its contestations of place and emotion (Benson 2012; Matthews 2013). Moreover, Jones, Jackson, and their contributors are clearly researchers who have taken seriously Les Back’s (2007) call for sociologists to listen attentively to their surroundings, and open their narratives to the stories that emerge in the field. This collection of essays immerses the reader in the lives and voices of the fieldwork participants and in doing so renders itself both a solid intellectual resource, but also – and importantly – a beautiful collection of insights into the emotional lives shaped by the changing nature of the cosmopolitan city. In short, this is a collection of essays which deserves to be read far more widely than urban studies; its methodological and theoretical richness is the kind that keeps on giving with every read.

——————————-

Sarah Burton is currently an ESRC-funded doctoral candidate at Goldsmiths College. Her research uses the concept of mess to investigate the value system(s) underpinning the production of knowledge in contemporary social theory. Having also spent several years involved in various artistic projects centring round theatre, classical music and writing/publishing, her academic research draws both on her formal education and also these forms of creative practice. Sarah convenes the British Sociological Association Postgraduate Forum and Activism in Sociology Forum, of which she is a founding member. Sarah also does lots of ‘fringe’ academia and is part of the collective working on the Woman Theory project. Read more reviews by Sarah.