In The Psychology of Strategy: Exploring Rationality in the Vietnam War, Kenneth Payne utilises the case study of the Vietnam War to show how psychology affects warfare, including discussion of confirmation bias, social identity and the psychology of fear. The book’s extensive subject matter and effective use of the Vietnam War as an illuminating prism offers an important contribution to the study of decision-making in International Relations, writes Michael Warren.

The Psychology of Strategy: Exploring Rationality in the Vietnam War. Kenneth Payne. Oxford University Press. 2015.

The most powerful man in the world slumped in tumultuous stress, powerless as his strategy crashes off the rails. This is the image that adorns the cover of The Psychology of Strategy: Exploring Rationality in the Vietnam War, displaying the centrality of psychology to military strategy. Kenneth Payne’s study is admirably broad in its scope of subject matter (from variable electric shock experiments on monkeys to the equally volatile moods of Richard Nixon), unifying a diverse range of theories and evidence to create a uniquely complete picture of how emotion and psychology can feasibly affect any war.

The most powerful man in the world slumped in tumultuous stress, powerless as his strategy crashes off the rails. This is the image that adorns the cover of The Psychology of Strategy: Exploring Rationality in the Vietnam War, displaying the centrality of psychology to military strategy. Kenneth Payne’s study is admirably broad in its scope of subject matter (from variable electric shock experiments on monkeys to the equally volatile moods of Richard Nixon), unifying a diverse range of theories and evidence to create a uniquely complete picture of how emotion and psychology can feasibly affect any war.

The book should not be treated as a history or policy analysis of the Vietnam War (there is a glut of those); rather, The Psychology of Strategy is first and foremost an ambitious guide on how ‘modern cognitive, evolutionary, social and emotional psychology’ affect warfare and its associated decision-making. The book gathers insights from across time and discipline (including Carl von Clausewitz, Stephen Pinker, Raymond Aron, Aristotle and other stellar thinkers) to comprehensively detail all perceptions of the psychological facets of war. Payne’s analysis of this thought-provoking compilation is then applied to the case study of the Vietnam War: chosen for its surfeit of sources, colourful mixture of antagonists and its well-trodden forensic analysis by academics who have gone before Payne. Thus, the Vietnam War serves as a unique (and maybe the only) militaristic event that can evidentially tie together themes of confirmation bias, social identity and the psychology of fear.

The psychology of fear, in fact, is one of the most fascinating motifs of the book. Weaving together a mixture of science and history, Payne reveals how scientific experiments on animals can shed light on the damaging psychological efficacy of bombing humans. US neuroscientist Joseph Brady in 1958 compared monkeys in two very perilous states: one set of tethered monkeys was repeatedly shocked with no control over the shocks, whilst the other set of monkeys (‘executive’ monkeys) was also repeatedly shocked, but could pull a lever to delay it. The latter group’s lever wrenching gave respite from the shocks for a mere twenty seconds longer than their comrades, but that was enough to create very profound outcomes. None of the tethered monkeys died during the experiment, whilst the ‘executive’ monkeys perished due to stomach ulcers, thus suggesting that control of one’s fate is a stressful endeavour. It is to Payne’s credit that he analyses myriad studies, both scientific and historical, which contradict and support the conclusions of the Brady experiment. The Brady study and others are neatly seen through the prism of the Vietnam War, and if there is one key lesson a belligerent can take from this interesting passage, it is that if you wish to bomb a country into submission, then do not gradually intensify bombing but bomb decisively before a population has time to acclimatise.

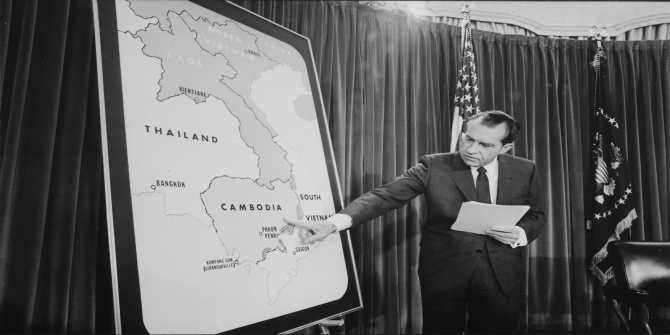

Image Credit: President Nixon Explains the Expansion of the War into Cambodia (Wikipedia Public Domain)

Image Credit: President Nixon Explains the Expansion of the War into Cambodia (Wikipedia Public Domain)

A common error when studying the effectiveness of a strategist is to focus on the outcome. Payne thankfully does not stumble into this trap, instead concentrating on processes leading to outcomes. However, within the process of decision-making, how much capacity of thought should be given over to chance? It is by no coincidence that Napoleon famously favoured generals infused with luck. How strategists deal with luck, or, to take it a rational stage further, how strategists deal with the awareness that their own data may not be complete, is instrumental to success. In the Vietnam War, General William Westmoreland pored over titanic amounts of data and concluded that if the enemy was killed in greater numbers on the battlefield than could be replaced, then the war would be won. Westmoreland’s strategic blinkers choked him from even conceiving of other factors to place in his equation, such as the incessant Vietnamese resolve and other operational designs. Alas, for Westmoreland, ‘what he saw was all there was’.

As Payne points out, though, not all strategists have fallen prey to this parochialism of ignoring the unknown. Although famous to many BBC Radio 4 listeners in the UK for his ‘Soundbite of the Week’ (a collection of gaffes and idiosyncratic phraseologies), Donald Rumsfeld firmly hit the nail on the head with his identification of ‘unknown unknowns’; or, as Payne explains, ‘things we do not even know that we do not know’. Making another interdisciplinary connection (to Daniel Kahnemann), Payne points out that without acknowledging unknowns, the mind creates causal links between whatever evidence is available and places insufficient weight on whatever mysteries lurk shrouded by the fog of war. This thought-provoking analysis has important lessons not just for today’s warfare, but in civilian arenas too. Living in a world of ‘big data’ and quantitative analytics means that the human race has never been so confident in informed decision-making, but a good decision-maker should still account for the unforeseeable.

The book’s subject matter is extensive and cleverly drawn together through the case study of the Vietnam War. There are some loose ends and room for exploration though. For example, the marginalisation of doubters amongst a decision-making group is definitely ripe for more research, particularly characters like George Ball who is simply distilled to the epithet of ‘the administration’s in-house Cassandra’. Additionally, if the war was so personal for Lyndon B. Johnson, why did his Republican successor feel so invested in it? Readers who enjoy The Psychology of Strategy are advised to read Laurence Freedman’s Strategy: A History (2013), which is similarly sprawling in scope, but with less military emphasis. The Psychology of Strategy is an important contribution to how International Relations and strategic specialists should consider actors’ decision-making. This is not a surrogate, though, for the aforementioned fields; rather, Payne’s stress on psychology should be infused and utilised in tandem with current modes of study.

___

Note: the above was originally published on LSE Review of Books.

Michael Warren completed an MSc in Empires, Colonialism and Globalisation at the LSE in 2012, and graduated from the University of Sheffield (studying on exchange at the University of Waterloo, Ontario) with a BA in Modern History in 2011. He researched on an open data project for Deloitte and the Open Data Institute, and worked for the All-Party Parliamentary Health Group and as a Management Consultant in Health and Public Service at Accenture. He is a Policy Adviser at the Professional Standards Authority. Read more reviews by Michael Warren.

1 Comments