Ben Worthy and Mark Bennister argue that Boris Johnson as Prime Minister was overvalued and oversold.

Ben Worthy and Mark Bennister argue that Boris Johnson as Prime Minister was overvalued and oversold.

Boris Johnson’s leadership has again come under scrutiny in the wake of the local elections, which proved to be at the far end of pollsters’ worst case scenarios. Initially, the reaction from Conservatives in England was relatively subdued, though by Saturday one unnamed MP was muttering that the Prime Minister was ‘killing our traditional vote’ and others that ‘partygate’ was coming up on the proverbial doorstep. Significantly for a Prime Minister who made himself Minister for the Union, the Scottish and Welsh Conservatives squarely blamed Johnson and his scandals. Ministers are now having to publicly insist their leader is ‘still an asset’.

How, in the space of three years, are we here? Johnson’s story as Prime Minister can be told through one of two narratives. One approach, let’s call it the Shakespearean tale, is of hubris and nemesis. This is a very human story of a populist and popular politician with a common touch, brought down by their personal failings, all very apt for a leader throwing out threats from King Lear. It is the rogue who finally got caught, or the gambler who bet the house and lost. A second way of understanding Johnson, we can call the ‘tides of fortune’ tale, is about context, and tells of a Prime Minister whose sunny optimism and sloganeering strengths on Brexit became weaknesses in the face of a deadly pandemic.

These two stories strike at the heart of how we think about leaders, and straddle the age-old question asked by Machiavelli, as to whether it is personality or context that matters in leadership. Do leaders manage to change the political weather or – whatever their perceived power and authority – are they stymied by forces beyond their control?

Depleted Leadership Capital

Each of these stories implies that Johnson was once strong and is now weak. However, using the idea of ‘leadership capital’, a rather different picture emerges. Leadership capital is the idea of a leader having a ‘stock’ of capital or authority that they can spend or lose over time. It is based on three core elements: skills, relations, and reputation. Much was made of Johnson appearing to have deep stocks of leadership capital, and having the ‘weather-making’ power to remake British politics however he wished. After months in power in 2019, one journalist claimed that Johnson’s ‘short period of time has been revolutionary, and his resounding victory means he can remake the country’.

However, there is a different story of fragility and oversell, rather than fallen ‘greatness’ or changing tides. To pick out a few strands, on close investigation his communication, popularity, and party relations are all more brittle than they had appeared.

Fragile Skills

Johnson’s communication skills were always seen as his major source of power, though his skills were very far from the oratory traditionally expected. His set-piece speeches have been bizarre failures, whether a ‘frantic diatribe delivered at such a pace that the audience looked bemused’ at a party conference or a key a speech to the CBI, which many hoped would set out a vision for levelling up, that instead focused on Peppa Pig World.

His influence, and supposed reach, lay in this informal style, coupled with an ability for self-mockery. His approach attracted attention, distracted opponents, and helped avoid difficult questions, often simultaneously. They also helped seal his ‘outsider-ness’ while also sending messages to certain voters. Yet somewhere between 2019 and 2022, Johnson’s style became subject to diminishing returns – an inverse Midas touch. His informal style proved particularly unsuited to the pandemic response, from his continued hand-shaking to allegations of much worse off-hand comments. His false accusations over Keir Starmer around Jimmy Saville exposed his darker side, provoking dissent in his own party. At the same time, voters became increasingly unhappy with the lies, distortion, and untruths that seemed part and parcel of his approach.

Fragile relations

There’s a similar fragility to his popularity. Johnson’s claim to ‘Heineken’ status and electoral appeal rests on his time as Mayor when he twice won in a Labour-controlled city.

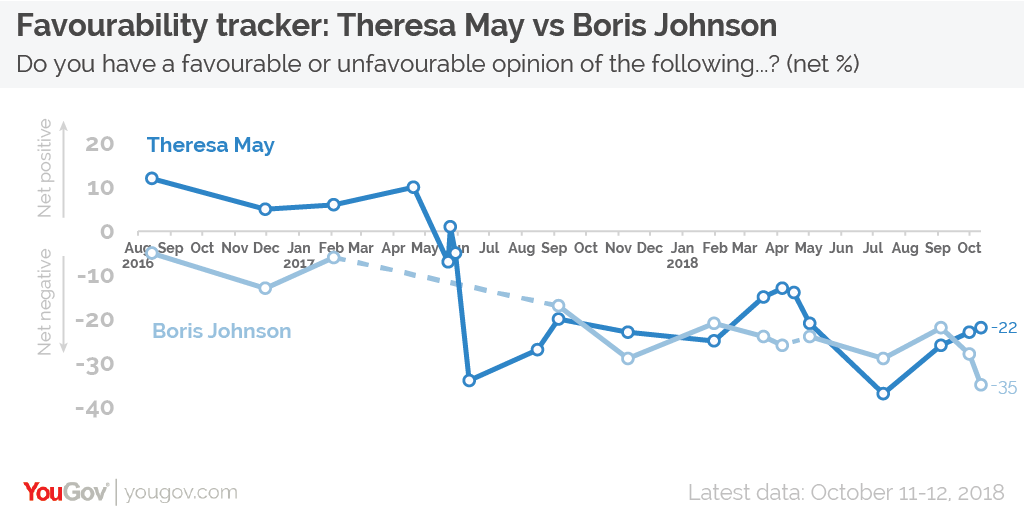

Yet data tell an interesting story of over-sell in Downing Street. As this YouGov analysis explains, ‘since the 2019 General Election, there has been something of a myth surrounding Boris Johnson – that he is (or was) a popular Prime Minister on which very little would “stick”.’ Theresa May was more popular than Johnson ever was, and his unpopularity has now plumbed depths May’s never reached. His popularity has always been relative, not absolute: it was dislike of Red Ken and Jezza that lost it, not love for ‘Boris’ that won it. The myth of Johnson as a ‘different’ and ‘popular’ politician was pushed along by media portrayals of a man who supposedly did quadratic equations to relax, and Conservative MPs hoping it was true.

This is not to say Johnson’s presence didn’t count at certain points. There was clearly a ‘Boris effect’ in 2016 and one study of Brexit concluded that he ‘had a particularly important effect –if you liked Boris then even after controlling for a host of other factors you were significantly more likely to vote for Brexit’. Again in 2019, Johnson’s impact was important but in a rather more narrow way of attracting parts of the leave vote, and was less about his popularity and more Jeremy Corbyn’s unpopularity.

But by 2022, Johnson’s electoral coalition of Red and Blue Walls, supposed to be the basis of new settlement in English politics, looks now increasingly fragile and unstable. After the 2022 local elections, it appears the Blue Wall is crumbling under the pressure of the Lib-Dems. In the famous ‘Red Wall’, as this Sky News analysis explains, ‘…the average voter didn’t like Boris Johnson any more than in other parts of the country. It was just that there were Leave voters there in higher numbers’.

Fragile Reputation

A final area of brittleness is his own party, which is as divided as the voting coalition which created it. Johnson should have presided over a group of MPs grateful for his election victory and getting Brexit done. His MPs have proved to be appreciative of nothing, making his current 73-seat majority extraordinarily shaky. He has faced rebellions on a whole range of issues, from NHS parking charges to lockdown laws. Instead of a Prime Minister passing laws and making changes to embed a reputation, there were continual U-turns and shifts. Since October 2021 and the Owen Paterson vote, relations have soured with the Conservative Parliamentary Party, with only ‘events’ putting off a leadership challenge over the rumbling partygate saga.

Johnson is neither a charismatic failure nor a tragic figure. He hasn’t made the weather simply because he has been oversold. As others have pointed out, Johnson’s time in office increasingly resembles Berlusconi’s: a supposed outsider promising change, coming to power amid a politics in deep flux, and sitting atop an unwieldly coalition and polarised country. Both were masters of over-promising and saying much (often controversially) but doing little. They even share a love of (unbuilt) bridges. But like Berlusconi, will it be scandal that finally removes him?

___________________

Ben Worthy is a Senior Lecturer in Politics at Birkbeck, University of London.

Ben Worthy is a Senior Lecturer in Politics at Birkbeck, University of London.

Mark Bennister is Associate Professor in Politics at the University of Lincoln.

Mark Bennister is Associate Professor in Politics at the University of Lincoln.

Featured image credit: by Andrew Parsons / No 10 Downing Street on Flickr under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 licence.