Thomas Guiney discusses the sudden changes concerning penal policy following Boris Johnson’s election, and explains what they reveal about the balance of power within the Conservative Party.

Thomas Guiney discusses the sudden changes concerning penal policy following Boris Johnson’s election, and explains what they reveal about the balance of power within the Conservative Party.

The American physicist Richard Feynman once said that, ‘if you think you understand quantum mechanics, you don’t understand quantum mechanics…’. He could just as easily have been talking about British penal policy. In the space of just 24 days during the summer of 2019, the government’s approach to crime and criminal justice has been turned on its head.

On 16 July 2019, David Gauke delivered what would prove to be his final speech as Justice Secretary. Returning to the themes that defined his tenure at the Ministry of Justice, Gauke set out his vision for a “smarter” justice system:

I believe the public therefore expect the justice system to focus on rehabilitation to reduce the risk of subsequent offending – and the likelihood of them becoming a victim of crime…. We need to punish for a purpose.

Gauke cast doubt on the effectiveness of short-prison sentences and drew attention to recent analysis by the Ministry of Justice which demonstrated that individuals serving custodial sentences of under 12 months demonstrate considerably higher levels of reoffending than those serving community sentences. With reoffending estimated to cost the taxpayer £18bn per year, Gauke expressed his hope that a future Conservative government would follow the Scottish example and introduce a statutory presumption against immediate custodial sentences of six months or less. These choices were outlined more in hope than expectation. Boris Johnson was announced as Prime Minister on the 24 July 2019 and Gauke subsequently resigned from the government.

During the Conservative Party leadership campaign Johnson had used his regular column in the Daily Telegraph to advocate for longer sentences for violent and sexual offenders. This overtly populist rhetoric was quickly translated into government policy. Launching what Downing Street would describe internally as ‘crime week’, Johnson set out his law and order credentials in The Mail on Sunday. His government would come down hard on crime and, with an eye to a possible Autumn election, pledged additional funding for crime control:

- The recruitment of 20,000 new police officers.

- The removal of restrictions on the use of stop and search and the launch of a new pilot programme that will enable 8,000 police officers to authorise enhanced procedures.

- A sentencing review of the most dangerous and prolific offenders.

- A £2.5bn investment in the construction of 10,000 new prison places.

- A £100m investment in prison security; including the installation of ‘airport-style ‘scanners throughout the prison estate.

Conservativism in conflict?

While it is tempting to view this volte-face through the narrow lens of personality politics, these events are jut as interesting for what they reveal about contemporary conservativism and the fluid balance of power within the Conservative Party. From Leon Brittan’s reforms of the parole system in 1983 to Chris Grayling’s much criticised privatization of the probation service in 2013, the shifting constellations of power between the One-Nation and Thatcherite voices within Cabinet have often gone hand-in-hand with periods of performative penal populism.

Crime may be a quintessentially conservative issue, but it cuts across several major fault lines within conservative thought and new right politics more generally; pragmatism and authoritarian populism; neo-liberalism and neo-conservatism; the local and the global, a fear of moral decline and an embrace of the free-market. These ideological traditions yield very different perspectives on penal policy-making, but it is impossible to understand how and why these ideas come to find expression in official policy without some reference to the competing demands of political statecraft. As the political scientist Jim Bulpitt noted:

What is statecraft? The crude answer is that it is the art of winning elections and achieving some necessary degree of governing competence in office… It is concerned primarily to resolve the electoral and governing problems facing a party at any particular time.

Commentators have rightly drawn attention to the highly questionable effectiveness, fairness and penological basis of these measures, but this is somewhat to miss the point.

‘Crime week’ decoded

Viewed through the lens of political statecraft, the current revival of law and order politics has less to do with crime and rather more to do with current parliamentary arithmetic and the Conservative Party’s future electoral prospects:

First, Johnson’s advisors have borrowed from the Thatcher play-book in seeking to position crime as a ‘wedge issue’ that puts clear blue water between the current government, the Labour Party, and Thresa May’s tenure as Prime Minister. This may prove altogether more difficult to pull off in the current climate.

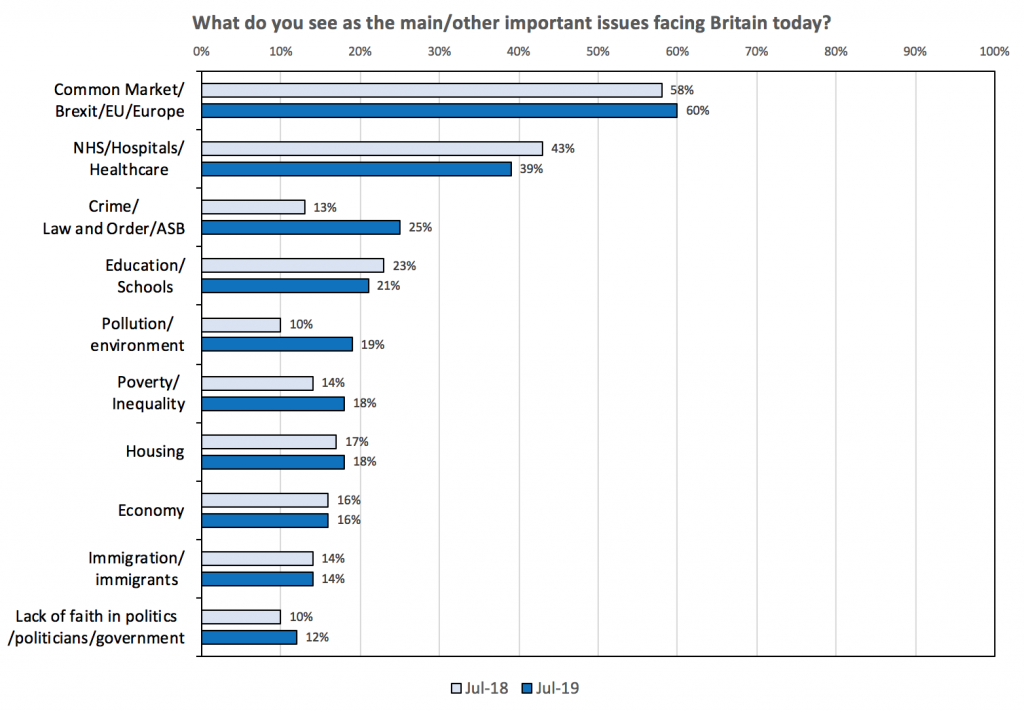

Law and order has barely featured in British general elections since 2001 and it is far from clear that public concern over knife crime and the release of high-profile offenders – such as John Worboys – will break through as a big-ticket electoral issue. As Figure 1 reveals, concern over crime has increased significantly in the past year, but still lags behind Europe and the NHS in the public’s priorities.

Figure 1

Ipsos Mori Issues Index, 2018-2019

Ipsos Mori Issues Index, 2018-2019

Second, in the eyes of many voters Johnson suffers from a credibility gap that was exposed during the leadership contest. His record in government was decidedly mixed and many have questioned whether he possess the temperament to be an effective Prime Minister. In recognition of this, Johnson’s team have repeatedly turned to criminal justice in order to present a counter-narrative based upon his experience as the Mayor of London and the successes (real or perceived) that he had in reducing knife crime across the capital.

Third, Johnson’s government has extremely limited room for policy manoeuvre. The Conservatives have a working majority in Parliament of just one, the civil service is consumed by Brexit planning, and the latitude for additional spending is severely constrained by the current budget settlement. Within such a restrictive operating environment, rhetorical shifts on emotive issues such as crime and immigration can deliver marginal gains despite the fact the underlying legislative or policy framework has remained largely unchanged; a process Steve Farrell et al have characterised as ‘communicative dissonance’.

Fourth, it is increasingly apparent that ten-years of austerity has become an electoral liability for the Conservative Party and a firm point of difference for Labour.

Decoupling the Conservative brand from its cornerstone economic policy, while maintaining a reputation for fiscal prudence, has proved extremely difficult. In this context investment in ‘frontline services’, such as the police, presents an attractive option for policy-makers seeking to square the circle of post-austerity politics.

Brexit: The ‘elephant in the room’….

Ordinarily these measures – in conjunction with recent announcements on public sector pay and the NHS – might be expected to appeal to the Conservative base and some swing voters. But these are very far from ordinary times. The fate of the current government is inexorably linked to Brexit and this single issue will continue to dominate the political agenda to the exclusion of all else. Europe has accentuated longstanding ideological differences within the Conservative Party (as it has within the Labour movement) and this promoted diametrically opposed positions on how best to respond to the challenges of contemporary statecraft.

The sudden change of direction on penal policy this summer may be the latest manifestation of this conflict, but it is unlikely to be the last.

_____________

Thomas Guiney is a Lecturer in Criminology at Oxford Brookes. His latest paper, Solid Foundations? Towards a Historical Sociology of Prison Building Programmes in England and Wales, 1959–2015 is published in the Howard Journal of Crime & Justice.

Thomas Guiney is a Lecturer in Criminology at Oxford Brookes. His latest paper, Solid Foundations? Towards a Historical Sociology of Prison Building Programmes in England and Wales, 1959–2015 is published in the Howard Journal of Crime & Justice.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Featured image credit: Pixabay (Public Domain).