Economic uncertainty following the EU referendum, as well as additional political uncertainty stemming from the recent High Court decision to allow Parliament to vote on the deal, might delay the government’s preferred timing for triggering Article 50 by March 2017. There is therefore potential for fuelling investment uncertainty and delaying a steady recovery in UK productivity, explain Michael Ellington and Costas Milas.

Economic uncertainty following the EU referendum, as well as additional political uncertainty stemming from the recent High Court decision to allow Parliament to vote on the deal, might delay the government’s preferred timing for triggering Article 50 by March 2017. There is therefore potential for fuelling investment uncertainty and delaying a steady recovery in UK productivity, explain Michael Ellington and Costas Milas.

The ongoing productivity puzzle – very weak productivity growth in the aftermath of the 2008-2009 financial crisis – leaves little room for strong wage increases. Consequently, tax revenues are weaker than otherwise leading to a persistent budget deficit. In fact, as Chris Giles, Economics Editor of The Financial Times, noted, “solving [the] productivity puzzle is key to public finances”. At the same time, rising inflation (expected by the Bank of England to reach 2.7 per cent in 2017) will put under rising pressure household expenditure and therefore undermine UK economic growth.

Much of the discussion about the productivity “puzzle” focuses almost exclusively on the relationship between productivity growth and real wage growth. This, however, ignores the potential impact of investment uncertainty. David Smith, Economics Editor of The Sunday Times, briefly focussed on this issue by noting that “there is the impact of uncertainty on investment…With businesses nervous about what the future will bring, this does not look like the climate for strong investment.”

In general, periods of economic stress are associated with elevated uncertainty. Consequently, firms pause hiring and investment. In the latter case, productivity growth takes a hit because the drop in hiring and investment reduces the rate of reallocation from low to high productivity firms; the negative effect also (arguably) transfers to wage growth.

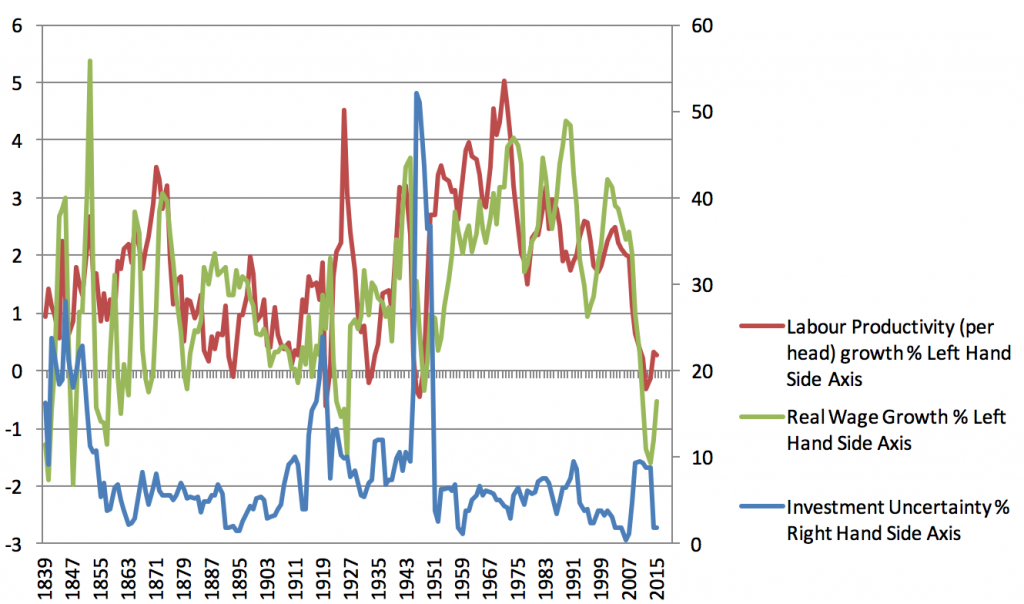

Using the Bank of England’s historical dataset, we plot together annual productivity (per head) growth, real wage growth and our measure of investment uncertainty. Productivity growth and real wage growth are 5-year moving averages. We construct investment uncertainty by taking the 5-year moving standard deviation of gross fixed capital formation growth (see Data Appendix).

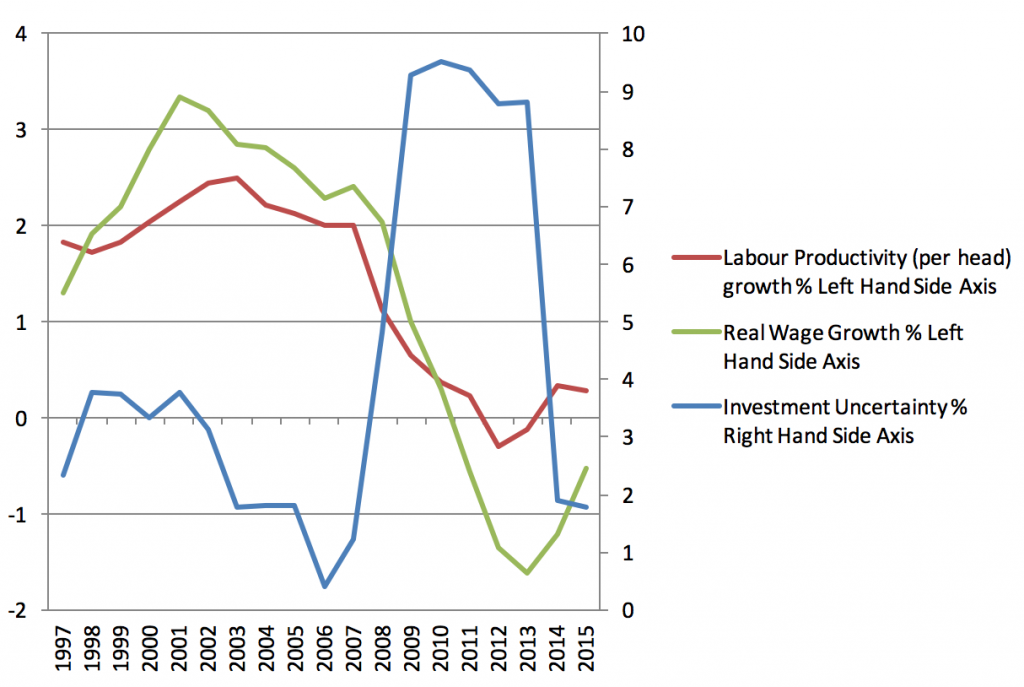

Figure 1 plots together productivity (per head) growth, real wage growth and investment uncertainty over 1839-2015. From Figure 2, which zooms into the 1997-2015 period, we see that low investment uncertainty coincides with steady productivity growth and real wage growth. Nevertheless, elevated uncertainty during the financial crisis in 2008-2009, takes a hit both on productivity and real wage growth.

Figure 1: productivity (per head) growth, real wage growth and investment uncertainty, 1839-2015

Figure 2: productivity (per head) growth, real wage growth and investment uncertainty, 1997-2015

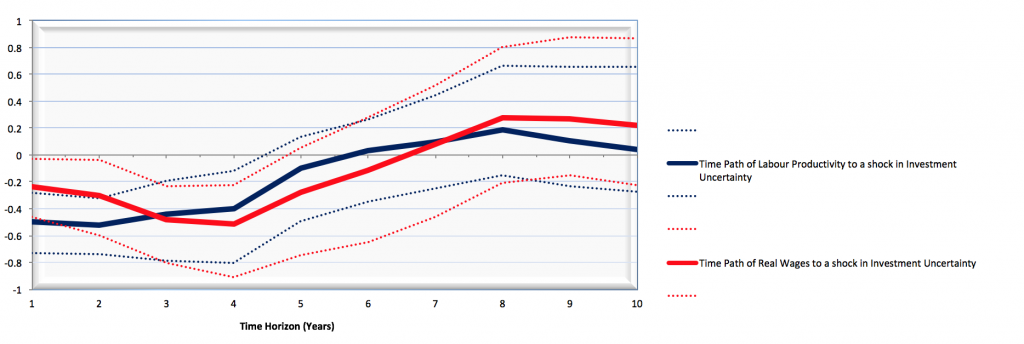

Figure 3 plots the posterior median (together with the 16th and 84th percentiles; dotted lines) response of productivity growth and real wage growth to a 1-standard deviation investment uncertainty shock in 2008. From Figure 3, investment uncertainty exerts a negative and statistically significant impact on productivity growth and real wage growth for up to 5 years. Our calculations are done within a 3-variate Time-Varying Parameter Bayesian Vector Autoregressive model (using a Minnesota prior) which is conditional on exogenous World War I and World War II effects.

Figure 3: Time Paths of Labour Productivity and Real Wages in the UK in response to a shock in Investment Uncertainty in 2008

What are the implications of Figure 3? Our model goes some way towards explaining why productivity and real wages have not fully recovered yet following from the big investment uncertainty shock during the financial crisis of the late 2000s. We therefore argue that investment uncertainty is a valuable missing piece of the productivity “puzzle” and has to be considered by econometric models.

From a policy point of view, economic uncertainty following from the recent Brexit vote as well as additional political uncertainty stemming from the recent decision of the High Court to allow Parliament to vote on Brexit (unless, of course, the Supreme Court decides otherwise) might delay Ms May’s preferred timing of triggering Article 50 by March 2017. All this has the potential of fuelling investment uncertainty and therefore delaying a steady recovery in UK productivity. In such a grim scenario, it will definitely be a challenge, as David Smith noted, to “survive in a post-Brexit world”.

Data Appendix

Labour productivity per head: We then construct annual growth and its 5-year moving average.

Wage index (spliced) and Consumer price index-original measure. We deflate the wage index by the consumer price index. We then construct the annual real wage growth and its 5-year moving average.

Gross fixed capital formation, composite measure, volume. We then constructed the annual growth and its 5-year moving standard deviation. This is our measure of investment uncertainty. All variables come from Bank of England’s “three centuries of data” (available here).

___

Michael Ellington is Research Fellow, University of Liverpool

Michael Ellington is Research Fellow, University of Liverpool

Costas Milas is Professor of Finance, University of Liverpool

Costas Milas is Professor of Finance, University of Liverpool

From the charts, it looks like the Labour government, within a year or two of 1997, had a devastating effect on both productivity and real wage growth. This may or may not stem from the massive de-industrialisation of the economy during their time in office, which is the sector in which other economies have seen major productivity growth.

The article introduces economic uncertainty as the missing factor in explaining growth of real wages and productivity, but does not mention any other factors. Stripping out economic uncertainty, what other correlation factors are found?