Marco Giuliani analyses the parliamentary Brexit process through an examination of the 12 indicative votes held in 2019 to find an alternative solution to Theresa May’s exit agreement. He maps the choices of each MP along two relevant dimensions, connecting them to the socioeconomic structure of their constituency as well as to the preferences expressed in the referendum.

Marco Giuliani analyses the parliamentary Brexit process through an examination of the 12 indicative votes held in 2019 to find an alternative solution to Theresa May’s exit agreement. He maps the choices of each MP along two relevant dimensions, connecting them to the socioeconomic structure of their constituency as well as to the preferences expressed in the referendum.

The Brexit parliamentary process perplexed observers of British politics. The frequency and magnitude of rebellions, government defeats, and ministerial resignations were unknown to Westminster and more typical of fragmented and unstable democracies.

Amongst the odd things that happened, Theresa May’s government – which had already twice lost the vote on the EU Withdrawal Act – lost control of the agenda and had to give way to parliament in trying to find alternative solutions. Several MPs proposed solutions to the conundrum – ranging from a no-deal exit, to a Customs union, to a new confirmatory referendum, or the revocation of Article 50 that ended up triggering Brexit – with the Commons dividing on twelve indicative votes: non-binding resolutions to ascertain the preferences of parliament on certain issues. These votes provide an unusual opportunity to understand how MPs behave in those exceptional circumstances where they are less tied to the typical Westminster adversarial style.

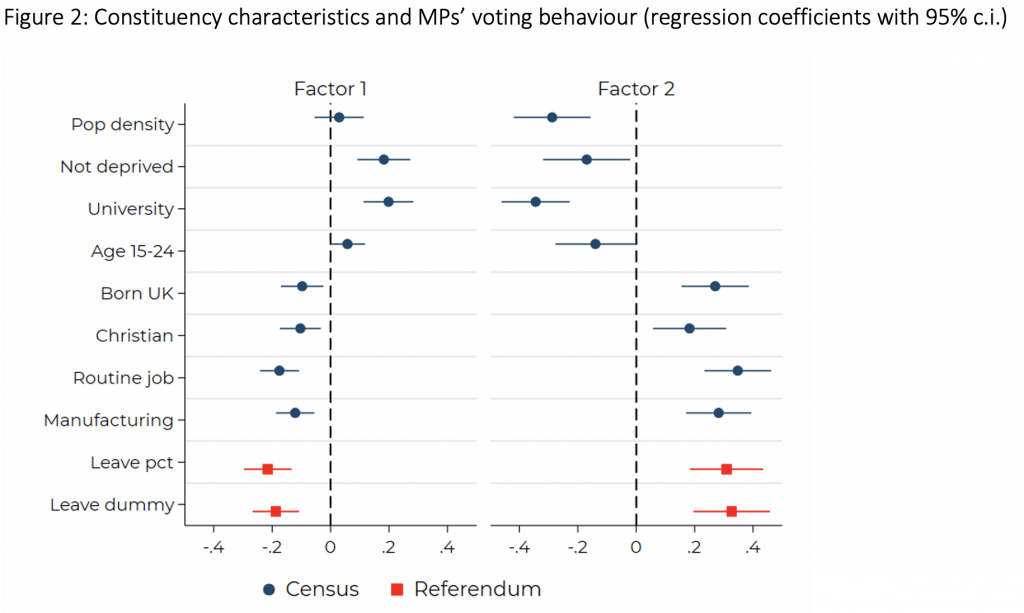

The good news for British democracy is that even in that extraordinary period, in which parties were so divided, MPs tried to remain loyal and accountable to their multiple principals, working in the interest of voters, the party, and the nation. My research explored how MPs reconciled these multiple principals during the twelve indicative votes, first by producing a comprehensive map of their behaviours (Figure 1), and then by explaining them through factors such as the socio-economic structure of their constituency, the referendum result, the seniority of the MP, the electoral margin in the 2017 general election, etc. Figure 1 places each MP close to other MPs with similar voting behaviour. The multiple locations and mix of colours reflect the blurring of party lines, contrary to what usually happens in a majoritarian democracy. Furthermore, two dimensions are needed to capture the variety of behaviours, again contrary to the traditional unidimensional adversarial space of competition in Westminster. Starting from the bottom-left part of the map and moving clockwise, we first meet a variegated group of hard-line Brexiteers (Tories close to the ERG, DUP members, and some Labour Eurosceptics) who rejected May’s agreement. Towards the centre of the map, we find government and opposition MPs preferring a no-deal but consenting to the prime minister’s plan; and then, on the upper side of the figure are those consistently supporting May’s efforts. On the right-hand side there are first the more negotiating MPs, then those accepting multiple soft exit solutions, and finally the group of Remainers who voted May’s agreement down and accepted a limited range of alternatives or supported more radical plans like a second referendum.

Figure 1 places each MP close to other MPs with similar voting behaviour. The multiple locations and mix of colours reflect the blurring of party lines, contrary to what usually happens in a majoritarian democracy. Furthermore, two dimensions are needed to capture the variety of behaviours, again contrary to the traditional unidimensional adversarial space of competition in Westminster. Starting from the bottom-left part of the map and moving clockwise, we first meet a variegated group of hard-line Brexiteers (Tories close to the ERG, DUP members, and some Labour Eurosceptics) who rejected May’s agreement. Towards the centre of the map, we find government and opposition MPs preferring a no-deal but consenting to the prime minister’s plan; and then, on the upper side of the figure are those consistently supporting May’s efforts. On the right-hand side there are first the more negotiating MPs, then those accepting multiple soft exit solutions, and finally the group of Remainers who voted May’s agreement down and accepted a limited range of alternatives or supported more radical plans like a second referendum.

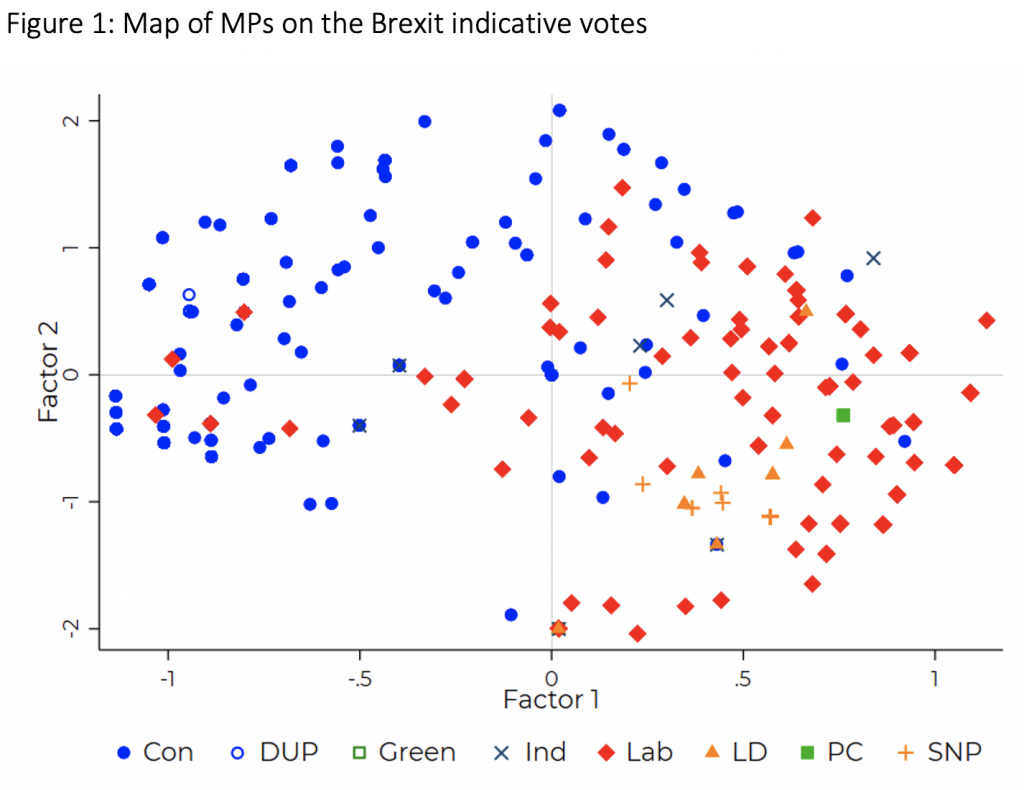

Most of the variation in voting behaviour (78%) happened on the horizontal axis, the one that better reflects the different exit options but also the more compromising MP attitudes. The vertical axis captures an additional 13% of the variation and is mostly associated with the support for, or rejection of, Theresa May’s exit agreement. A series of regressions, whose coefficients are plotted in Figure 2, show that the positioning of MPs in Figure 1 along those two dimensions is not idiosyncratic; rather, when controlling for party membership, it reflects important constituency characteristics.

Interestingly, the factors associated with MPs’ voting behaviour, representing the socio-economic structure of constituencies as well as the preferences expressed by constituents, are symmetrically associated with the two dimensions of Figure 1. The vote in favour of Brexit is negatively associated with the positions on the left side of Figure 1, while it is positively related to the positions on the upper part. Again, representatives of less deprived constituencies with a larger number of university graduates tend to be more compromising, accepting multiple soft exit alternatives, while the opposite is the case for MPs elected in less homogeneous constituencies, such as those with higher shares of voters born in the UK, with higher shares declaring themselves as Christian, or holding manufacturing and routine occupations. Conversely, these latter factors played a positive role in triggering the support of Theresa May in her effort to deliver Brexit, as asked by the majority of the electorate.

Finally, my research also found that some MPs more or less strictly followed the structural interests and political preferences made explicit by their constituents, or the position of the majority of their party colleagues. Senior representatives in safer districts typically enjoyed larger margins of freedom in their behaviour, following more their personal ideological beliefs or what they perceived to be the best interest of the country. However, on average, betraying those preferences had a cost in the 2019 general election for MPs of all parties. This finding closes the circle of representation, with MPs interpreting the interests of their constituency, and voters rewarding or punishing their parliamentary behaviours depending on their accountability or lack of responsiveness.

No indicative votes expressed an alternative supported by a majority of MPs, although the final result did not represent their preferences either, so that the deadlock led to Johnson’s new exit plan and the 2019 general election. The failure of those divisions indicates a lack of familiarity with cooperative dynamics, and it is probably fair to say that if the parties had more experience with consensual practices, the story might have had a different outcome.

____________________

Note: the above draws on the author’s published work in Government and Opposition.

Marco Giuliani is Professor in the Department of Social and Political Sciences at the University of Milano.

Marco Giuliani is Professor in the Department of Social and Political Sciences at the University of Milano.

Photo by Thor Alvis on Unsplash.