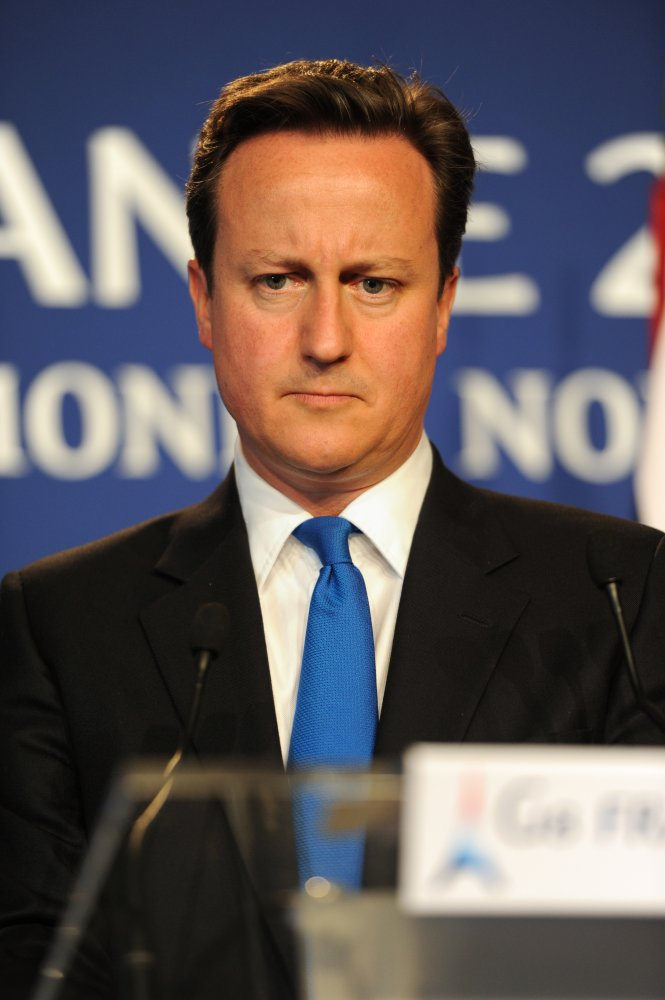

David Cameron’s political career was cut short by last year’s dramatic Brexit vote. Chris Byrne, Nick Randall and Kevin Theakston look back on his time in office, and how the history books will judge him.

For David Cameron 2017 will be a year of ‘exciting new challenges’. Chief among these will be joining the after dinner speaking circuit of former prime ministers and working on his memoirs. Both will demand he defend and rationalise his political legacy. The challenge facing him will be to overturn the conclusions arrived at by many commentators in June 2016. For most Cameron’s resignation was further confirmation, if any were needed, that “All political lives, unless they are cut off in midstream at a happy juncture, end in failure”.

But Cameron’s premiership deserves an evaluation which recognises both his agency and the constraints arising from the conditions in which he governed. Such an assessment can be constructed by building upon Stephen Skowronek’s account of presidential leadership. This evaluates leadership performance by reference to the leader’s stance towards the prevailing ‘regime’ (a set of ideas, values, policy paradigms and their political interests and supports) and the extent to which that regime is resilient or vulnerable.

Cameron was committed to defend the regime he inherited from New Labour. Its political economy centred upon prioritising the interests of internationally mobile capital. It accepted the uploading of state responsibilities to supranational institutions, most controversially the EU, devolution of responsibilities to sub-state institutions and the transfer of responsibilities to communities, families, charities and market mechanisms. It situated these commitments within a neoliberal discourse and constructed an electoral coalition of the aspirational and entrepreneurial among the skilled working and middle classes. He also supported a set of deeper sedimented regime imperatives: preservation of the political union between the nations of the UK, maintenance of Britain’s international trading interests, a balance of power in Europe and the Anglo-American relationship.

But Cameron entered office at a moment when this regime was enervated and more vulnerable than at any time since the early 1980s. The continuing effects of the financial crisis and public dismay of the actions of financial institutions and multinationals testified to political-economic vulnerabilities. Elites in other institutions seemed increasingly disconnected from the public. Insurgent parties, in particular the SNP and UKIP, profited from and further generated regime vulnerabilities.

As the affiliate of a vulnerable regime Cameron was, in Skowronek’s terms, a ‘disjunctive leader’. Such leaders have limited options to establish their authority. They tend to seek to buy time and wait out events in the hope that conditions change. They find themselves driven into policy u-turns and policy experimentation. Their reputation for governing competence suffers and they face the accusation that they are pragmatists bereft of ideological conviction.

Cameron negotiated many of the challenges and constraints of disjunctive leadership relatively successfully. He fostered an image of competence relative to his rivals. He effectively disassociated himself from many regime failings. For example, by magnifying the economic difficulties he inherited he was able to lower expectations and bought political cover when economic targets were missed. He also frustrated potentially regime-changing reforms such as electoral reform and statutory regulation of the press. That Cameron, unlike other affiliates of a vulnerable regime such as Heath (1970-74) and Callaghan (1976-79), was able to secure re-election in 2015 was a signal of his successes as a disjunctive prime minister.

However, his claim to be serving national rather than partisan or sectional interests was eroded. For example, abolition of the 50p top rate of tax and his government’s austerity measures seemed to run counter to claims that “we’re all in it together”. Cameron failed to establish a clear policy vision. Neither the ‘Big Society’ nor equipping Britain for success in ‘the global race’ gained traction. Cameron also fell victim to avoidable errors, policy failures and abrupt u-turns. For example, the 2012 Budget descended into an ‘omnishambles’. The UK’s AAA credit rating was surrendered. The target to reduce immigration to ‘tens of thousands’ was repeatedly missed. Cameron also struggled to contain intra-party divisions. The 2010-15 Parliament was the most rebellious since 1945. Large scale rebellions took place on Europe, military intervention in Syria and House of Lords reform. That the majority of Conservative MPs refused to support same-sex marriage revealed a conflict between Cameron’s social liberalism and the social conservative plurality in his parliamentary party.

Ultimately, Cameron’s premiership was undone by the forces unleashed by the 2016 EU membership referendum. At root this had its origin in Cameron’s tendency – shared with other disjunctive leaders – to seek to buy time and wait out events. The referendum commitment united most shades of opinion within his party in the short-term. But Cameron became boxed in by this commitment after winning the 2015 election. He subsequently failed to manage expectations; there was no guarantee that he could secure “fundamental, far-reaching change” that would be acceptable to his party or the electorate. His party divided once again, more severely than he or commentators anticipated. And Cameron discovered that he had provided a platform for the populist appeals of Nigel Farage and UKIP and Boris Johnson. But most significantly, Cameron’s decisions unleashed longer-run and structural forces both beyond his control and the capacity of the regime to address – the growing salience of immigration as a political concern and the alienation of those ‘left behind’ by the social and economic changes associated with this regime.

Accordingly, the challenges of disjunctive leadership proved beyond the significant skills which Cameron had demonstrated between 2010 and 2015. He bequeathed to his successor a regime more profoundly vulnerable than he, and most other post-war prime ministers inherited. Not only does Theresa May face the challenge of reversing the uploading of state responsibilities to the EU over the past 43 years. She will need to resolve the positions of Scotland and Northern Ireland in a post-Brexit UK and negotiate the dilemma of responding to demands for control of immigration while addressing the concerns of powerful business interests about access to European markets. That some detect in her premiership thus far indecision, lack of policy vision and a tendency to u-turn is testimony to the formidable challenges of leading a vulnerable regime.

—

Note: This blog is based on the authors’ recent article in the British Journal of Politics and International Relations.

Chris Byrne is a Lecturer in Politics at the University of Exeter.

Nick Randall is a Senior Lecturer in the School of Geography, Politics and Sociology at Newcastle University.

Kevin Theakston is a Professor in the School of Politics and International Studies, University of Leeds.

Cameron set his political objectives on the dismantling of the state as did his predecessors, that has been the Neo-Liberal objective from 1970 onwards. He has now passed the baton on to Theresa May who has the task of completing it without the public at large realising it, which of course is doomed to fail.

A leader of a party that promises there will be no top down reorganisation of the NHS, and then upon getting into office rushes headlong into the total dismantling of it must go down in history as one of the greatest political charlatans of all time.

The media has sustained a total clamp down of factual information relating to all events political, they have managed the news to the nth degree to cover up the corruption that exists in our political system, even the BBC’s so called journalists have conspired to undermine a Labour Politician.

When I look at the manner in which modern political discourse has taken place, I say where are all the good men/women who appear to have conveniently forgotten our recent history?

I think Cameron’s biggest failure by far was his speech on 24th June. I’ve blogged about it at https://letsremainincontrol.wordpress.com/2017/01/16/david-camerons-worst-mistake/

Briefly, I think he stupidly set the tone for subsequent debate; he could easily have handed to parliament the responsibility to take things forward, without prejudging the issue.