What was the impact of Brexit on the 2017 general election result? What difference did the collapse of UKIP make? And what was the relative importance of factors such as turnout, education, age, and ethnic diversity on support for the two main parties? In a new article forthcoming in Political Quarterly, Oliver Heath and Matthew Goodwin answer these questions.

What was the impact of Brexit on the 2017 general election result? What difference did the collapse of UKIP make? And what was the relative importance of factors such as turnout, education, age, and ethnic diversity on support for the two main parties? In a new article forthcoming in Political Quarterly, Oliver Heath and Matthew Goodwin answer these questions.

Theresa May’s gamble was that the path to a commanding majority ran through not only retaining the 330 seats that the Conservative Party held, including an estimated 83 of which had voted to remain in the EU, but also by capturing a large number of Labour’s 229 seats, especially those among the estimated 149 that had voted for Brexit. In essence, this gamble rested on an assumption that the Conservative Party would retain votes in the typically more prosperous, more highly educated, urban areas that had tended to back Remain, while making big inroads among more economically disadvantaged, less educated and working-class areas which had voted for Brexit.

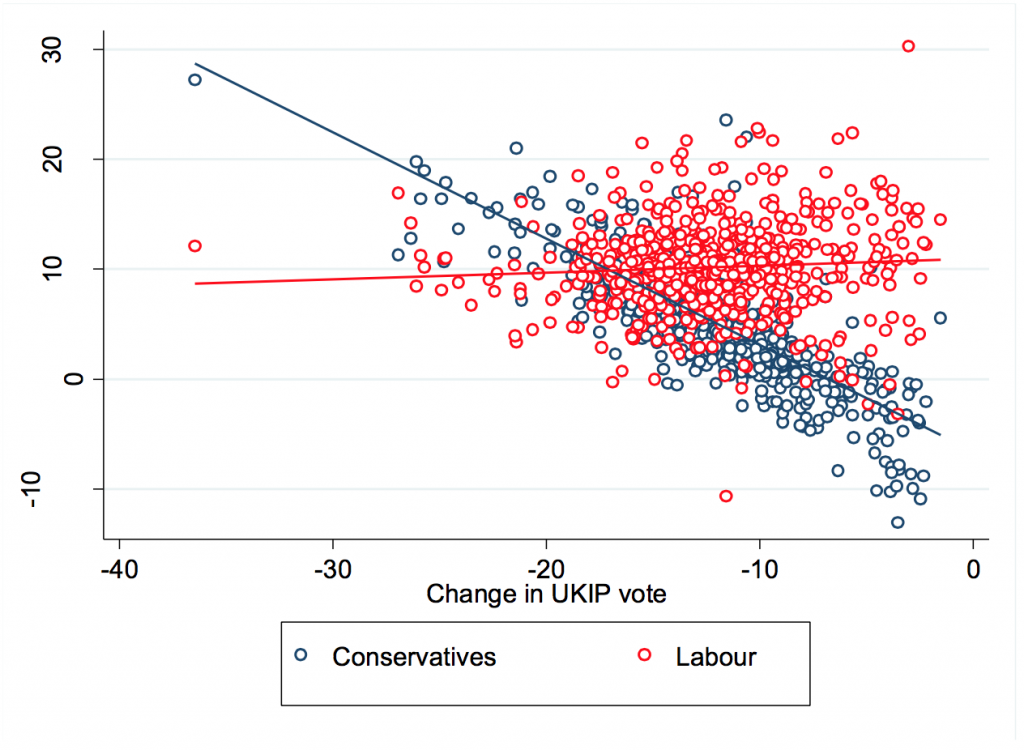

Our analysis shows how this gamble backfired. Figure 1 shows the relationship between Chris Hanretty’s constituency level estimates of the Leave vote and change in support for Labour and the Conservatives. We restrict our analysis to England and Wales, as a rather different set of factors are relevant for understanding electoral competition in Scotland. There is a slight tendency for Labour to perform better in places which supported Remain, but even in places which voted Leave, Labour’s share of the vote still improved. By contrast, the Conservatives lost votes in places that were very pro-Remain, but gained votes in places that were very pro-Leave. However, it was only in the most staunchly Leave areas where their gains outstripped those made by Labour.

Figure 1: Estimated support for Leave and change in support for Labour and Conservatives

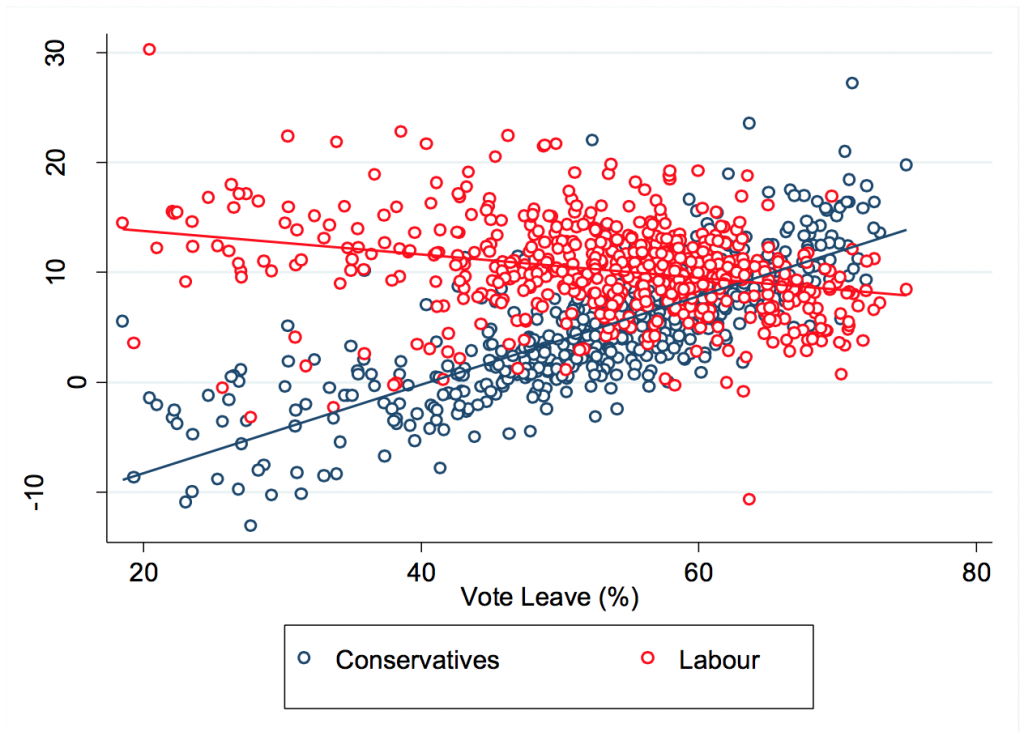

Going after such a hard Brexit may not have paid the dividends that the Tories expected. No doubt one reason why May opted for this approach was to try and appeal to the nearly four million people who had voted for UKIP in 2015. From Figure 2, we can see how the collapse of UKIP affected support for the two main parties. Labour did not do much worse in places where UKIP lost a lot of ground than in places where UKIP’s vote held up. But there is a much clearer pattern with respect to the Conservatives, who did well in places where UKIP lost a lot of votes, but badly where UKIP only lost a few votes. UKIP needed to lose close to 10 percentage points of the vote before the Conservatives saw any increase in their own share of the vote.

Figure 2: Change in support for UKIP and change in support for Labour and Conservatives

This suggests that whatever gains the Conservatives made from UKIP were offset by losses elsewhere. The results of our analysis provides clear evidence that the gains the Conservatives made from the collapse of UKIP were conditioned by the educational profile of the constituency. Conservative gains from UKIP in low skilled areas were offset by the losses they received in places where there were a larger number of graduates (which had previously tended to back the Conservatives). Thus, the Conservatives only registered any benefit from UKIP’s collapse in places where there were relatively few graduates. But in places where there were many more graduates, the Conservative vote share suffered.

This suggests that whatever gains the Conservatives made from UKIP were offset by losses elsewhere. The results of our analysis provides clear evidence that the gains the Conservatives made from the collapse of UKIP were conditioned by the educational profile of the constituency. Conservative gains from UKIP in low skilled areas were offset by the losses they received in places where there were a larger number of graduates (which had previously tended to back the Conservatives). Thus, the Conservatives only registered any benefit from UKIP’s collapse in places where there were relatively few graduates. But in places where there were many more graduates, the Conservative vote share suffered.

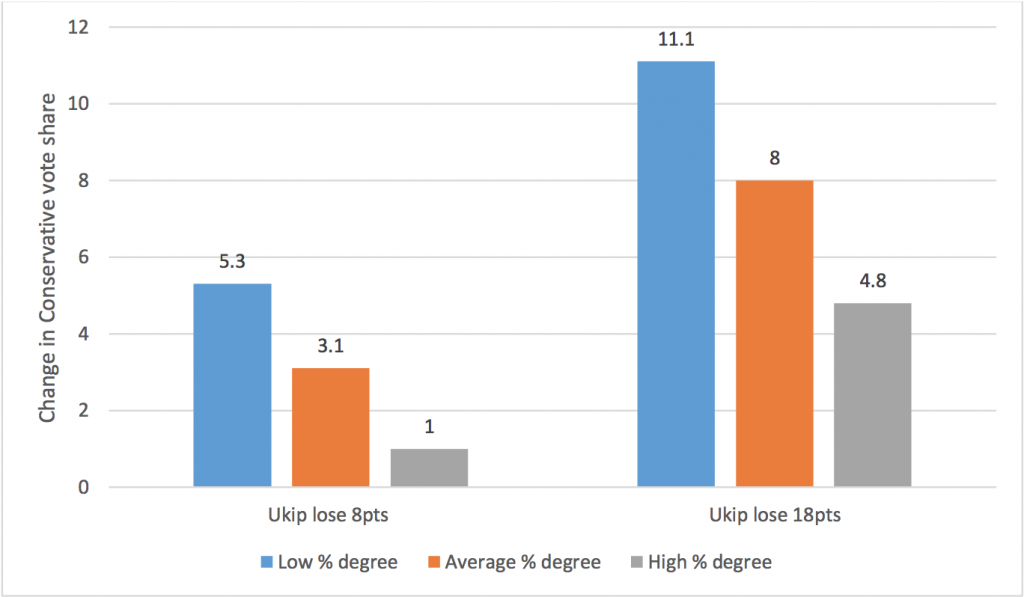

Figure 3: Estimated Conservative gains from UKIP losses

We can illustrate these patterns by calculating the estimated impact of UKIP’s decline on the Conservative vote in different types of areas, as shown in Figure 3. In relatively low-skilled areas, where there were slightly fewer graduates than average, the Conservatives were very effective at turning UKIP losses into Tory gains. In these sorts of places, an 8-point drop in UKIP’s share of the vote translated to about a 5-point gain for the Conservatives. However, in relatively high-skilled areas, the Conservatives were not nearly so effective at turning UKIP losses into Tory gains. In these sorts of places an 8-point drop in the UKIP vote translated into just a 1-point gain for the Tories.

There thus appears to be a trade-off between the appeals that the Conservatives made which had particular resonance in more deprived areas, which allowed them to make substantial gains at the expense of UKIP, and how those same appeals were received in more high-skilled areas, where they lost votes and needed big swings away from UKIP in order to just stand still. Theresa May’s strategy of aggressively courting the 2015 UKIP vote might therefore have backfired, and been at least partially responsible for the Conservative Party losing seats, particularly in London, the South East, and the South West.

_____

Note: this draws on research from a forthcoming article in The Political Quarterly.

Oliver Heath is Professor of Politics at Royal Holloway, University of London and co-director of the Democracy and Elections Centre. He tweets as @olhe.

Oliver Heath is Professor of Politics at Royal Holloway, University of London and co-director of the Democracy and Elections Centre. He tweets as @olhe.

Matthew Goodwin is Professor of Politics at the University of Kent, and Associate Fellow at Chatham House. He tweets as @GoodwinMJ.

Matthew Goodwin is Professor of Politics at the University of Kent, and Associate Fellow at Chatham House. He tweets as @GoodwinMJ.

1 Comments