In a new report on the economic consequences of a ‘Brexit’, Gianmarco Ottaviano, João Paulo Pessoa, Thomas Sampson and John Van Reenen find that if the UK left the European Union there would be a significant negative impact. The most important costs would come as a result of higher trade barriers with the EU.

Since a speech by the Prime Minister in January 2013, the Conservative party has been committed to holding a referendum on the UK’s membership of the European Union (EU) in 2017. So what would be the consequences of a majority vote in favour of leaving? Our new report finds that so-called ‘Brexit’ is likely to have a significant negative impact on the UK economy.

Eurosceptics emphasise greater national sovereignty from leaving the EU while Europhiles talk about the longstanding benefits of ever closer unity to reduce the risks of military conflict. These are important considerations, but our work focuses on the more mundane (but quantifiable) economic effects of Brexit.

Leaving the EU would bring home about half a percentage point of national income, since the UK would transfer fewer resources to subsidise poorer EU members. This would be the main economic benefit of Brexit. The most important cost would be lower trade with the EU. Higher trade barriers would reduce the UK’s ability to specialise in industries where it has a comparative advantage, leading to a fall in income. Our analysis uses a state-of-the-art quantitative model of international trade to estimate the effects of Brexit on trade and quantify the consequences for national income.

Estimating the effects of Brexit on trade and national income

It is not known what relationship the UK would have with the EU following Brexit, so we consider two scenarios: an optimistic scenario in which the UK continues to have relatively easy access to EU markets; and a pessimistic scenario with higher trade barriers. In the pessimistic scenario, we assume that there will be some tariffs on UK-EU goods trade. This seems reasonable immediately following withdrawal, but some argue that the UK may be able to negotiate a better tariff deal in the medium term. Hence, in our optimistic scenario, we assume tariffs continue to be zero.

Another important source of trade costs lies in non-tariff barriers such as regulations and other legal obstacles that affect not only goods but also services trade. Nowadays, such barriers are more important than tariffs in most developed economies. In fact, the main goal of the proposed Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership between the EU and the United States is to reduce non-tariff barriers. In our analysis, we assume that such barriers would increase after Brexit, with a larger rise in the pessimistic case than in the optimistic one.

Finally, intra-EU trade costs have been steadily falling over time – approximately 40 per cent faster than in other OECD countries. A decade from now, non-tariff barriers inside the EU are likely to be smaller and the UK would not reap these benefits after Brexit. In our pessimistic scenario, we assume that such barriers continue to fall 40 per cent faster than in the rest of the world, while in the optimistic case, we assume that intra-EU barriers fall only 20 per cent faster, implying that the UK has less to lose in the event of Brexit.

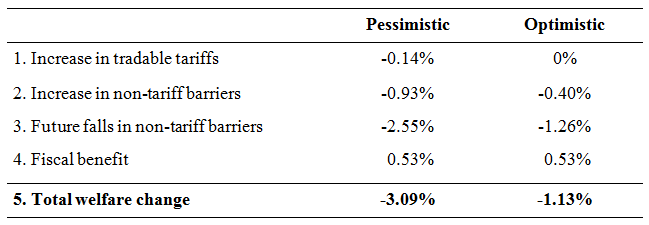

Taking account of all these effects, we find that Brexit would decrease UK income by 1.13 per cent in the optimistic case and 3.09 per cent in the pessimistic case. Thus, the costs of lower trade far outweigh the fiscal savings. Most of the impact comes from changes in non-tariff barriers, which are particularly important in services where the UK is a major exporter. In cash terms, the loss is £50 billion in the pessimistic scenario and a still substantial £18 billion in the optimistic one.

Table 1: Welfare changes in the UK if the UK leaves the EU (static model)

Notes: Welfare measured by change in real consumption in the UK

Source: Ottaviano, Pessoa, Sampson and Van Reenen (2014)

Growth

But the numbers in Table 1 underestimate the costs of Brexit as they do not consider other consequences of reduced trade that are likely to reduce income, but are harder to quantify numerically. In particular, they do not allow for the ‘dynamic’ effects of trade on growth, boosting productivity via more competition, innovation and adoption of technologies.

Using a different approach that factors in more realistic dynamic losses from lower productivity growth, a conservative estimate would double losses to 2.2 per cent of GDP even in the most optimistic case. In the pessimistic case, there would be income falls of 6.3 per cent to 9.5 per cent of GDP. These estimates are much higher than the costs obtained from the static trade model, implying that the dynamic gains from trade are important. To put these numbers in perspective, during the 2008/09 global financial crisis, the UK’s GDP fell by around 7 per cent.

Other economic effects: regulation, immigration, foreign direct investment

Brexit will not only affect trade, but also foreign direct investment (FDI), immigration and new regulations. The UK received the most FDI of any European country in 2011, and was second only to the United States in terms of the stock of inward FDI around the world. Part of the attraction is as an export platform to the rest of the EU, so if the UK is outside the trading bloc, this position is likely to be threatened. This matters because foreign multinationals tend to be high productivity firms and they bring new technologies and management skills with them.

Outside the EU, the UK could restrict immigration from the rest of the EU and vice versa. In economic terms, migratory flows act much like trade as people tend to move to where they can be more productive and earn higher incomes. Studies find that restricting mobility will, just like restricting trade, reduce UK overall welfare. Moreover, other evidence suggests that there have been no negative effects on jobs and wages of native Britons from waves of EU immigration. So even on distributional grounds, immigration does not seem to have been damaging.

Currently, the UK is able to influence the regulations governing the EU single market. Even if the UK maintained full access to the single market, it would be in the same situation as Switzerland: UK exports would have to follow these regulations without being party to setting them.

In sum, our current assessment is that leaving the EU would be likely to impose substantial costs on the UK economy and would be a very risky gamble. The dream of splendid isolation may turn out to be a very costly one indeed.

For more details see ‘Brexit or Fixit? The Trade and Welfare Effects of Leaving the European Union’

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

About the Authors

Gianmarco Ottaviano is Professor of Economics at the London School of Economics and Globalisation Research Programme Associate at the Centre for Economic Performance.

Gianmarco Ottaviano is Professor of Economics at the London School of Economics and Globalisation Research Programme Associate at the Centre for Economic Performance.

João Paulo Pessoa is an occasional research assistant in CEP’s productivity and innovation programme. He started his MRes/PhD in economics at LSE in 2009. Before coming to LSE he worked as a financial products analyst for three years at BBM Bank.

João Paulo Pessoa is an occasional research assistant in CEP’s productivity and innovation programme. He started his MRes/PhD in economics at LSE in 2009. Before coming to LSE he worked as a financial products analyst for three years at BBM Bank.

Thomas Sampson is a Lecturer in Economics at the London School of Economics. Globalisation Research Programme Associate at the Centre for Economic Performance.

Thomas Sampson is a Lecturer in Economics at the London School of Economics. Globalisation Research Programme Associate at the Centre for Economic Performance.

John Van Reenen is Professor in the Department of Economics London School of Economics and the Director Centre for Economic Performance, London School of Economics. He is also Fellow of the British Academy, Econometric Society and the Society of Labour Economists.

John Van Reenen is Professor in the Department of Economics London School of Economics and the Director Centre for Economic Performance, London School of Economics. He is also Fellow of the British Academy, Econometric Society and the Society of Labour Economists.

Dear UK friends

Dont listen to all the nonsense which is written and said about how bad the situation will be if you leave the EU. Look at Switzerland and do the same. If all the mainstream representatives and the media tells you desperately to do something – be very suspicious and do the opposite. They are arrogant enough to tell you they know what bad things happen in the future if you quit the EU. Hell, how do they know. They don’t! Vote to go out. The EU is a dictatorship. So don t let them fool you. The EU wants to have the sole power at the end. They want all powers of the different countries to go to Brussels where only a bunch of apparatchiks and bureaucrats govern. They will suppress every effort by the member countries to decide things by themselves. See how they treat Hungary and others. They want their judges and the EU parliament to be the only one to have the saying. All countries have to follow. They want to RULE and DICTATE. If you stay, they probably will increase the pressure on Britan the next day. So get out as long as you still can. May the courage be with you to do so!

Concerned Swiss citizen

I have read with great interest your views and one point can not be changed. Europe for all its stated values is not fit for purpose. They are slow to implement change unless it benefits them. We had a directive and countries needed to meet a specific criteria to join – this has not happened There is an impact ‘at street level’ and all your crunching of numbers and speculation does not change the fact that our schools,health service and housing can not cope. Please remember that Germany have a youth population problem or should I say lack of one. This will have an impact upon that countries economy. The opening of the gates by Germany was not a humanitarian act but a financial one.

Further evidence on the UK’s economic performance relative to other EU countries has appeared in “The Economist.”

http://www.economist.com/news/britain/21610246-when-it-was-last-size-britains-economy-looked-very-different-resized-and-reshaped?fsrc=scn/tw/te/pe/ed/resizednadreshaped

In support of the general argument in the original article, the UK has hardly demonstrated a stellar performance outside the Euro zone.

UK GDP performance and productivity has been relatively poor for some time. The UK’s recession was deeper and longer than that in any of our EU country colleagues.

http://www.bruegel.org/nc/blog/detail/article/1410-chart-the-uk-reaching-pre-crisis-gdp-levels/?utm_source=&utm_medium=Social&utm_campaign=bru.gl

It is unlikely that a Brexit would improve matters on either productivity or GDP. Recent Bank of England MPC Member produced policy paper suggest possible misplaced complacency on payments balance.

NB it should be stated that earlier remarks appearing above were made in response to Sue Jameson’s simple soundbite.

Sorry to burst your bubble chaps but this is a matter of democracy. Nothing, I repeat, NOTHING else matters except the freedom to govern our own country. Got it? Good.

Have we asked the entire population whether they care about these supposed “threats to democracy” more than, you know, jobs, prosperity, living standards, public services and all that other stuff that makes an actual difference to people’s lives? Of course not. As usual we have someone presuming to tell us what people want, without offering any evidence to back it up – and yet claiming to be in support of democracy.

The EU’s democratic deficit is real, but it’s also grotesquely exaggerated. The vast majority of policy areas are still retained by Westminster – taxation, education, health, foreign policy, criminal justice, etc. The only reason people don’t think that’s the case is that they’ve been bamboozled into thinking the integration process has gone much further than it has by bankrupt soundbites such as UKIP’s “75% of laws come from Brussels”.

Worse, they seem to genuinely believe that the Commission has the power to dictate laws, which has never been the case, at any point, in the history of the integration process. If you think that’s the case then you simply don’t know how the EU works – no ifs, no buts, no debate, it’s a logical error on your part, nothing less.

You’d actually be hard pushed to find a single genuinely important law coming from the European Union which has been pushed through against our government’s wishes. Even our supposed “inability to control our own borders” is an explicit policy supported by our government. They support free movement of labour because it benefits our economy immensely and we only have it because our government voluntarily signed a treaty to that effect.

Is the economy everything in politics? Not quite, but it’s certainly more important than the kind of democratic problems the EU actually causes us as British citizens – that’s the real European Union, not the bizarre folk tale UKIP have constructed about bureaucrats “dictating 75% of our laws”.

You cannot join the EU without being a Democratic country and committing to promote those values.

The argument to leave the EU is based on two connected philosophical premises; one economic the other political. 1. Protectionism. 2. Nationalism.

These two premises, widely applied across Europe led to two world wars and the Great Depression. We need to learn the lessons from 20th Century Nation State driven politics, not repeat them. Got it?