The defence review is occurring at a time of extreme financial pressure at home and considerable military risk in Afghanistan. Gwyn Prins and Sir Jeremy Blackham argue that geopolitics prescribe a primarily maritime framework for the Strategic Defence Review. The core strategic challenges remain naval ones, yet the Royal Navy has become dangerously weak. Urgent steps must be taken to reverse this trend before it is too late.

The defence review is occurring at a time of extreme financial pressure at home and considerable military risk in Afghanistan. Gwyn Prins and Sir Jeremy Blackham argue that geopolitics prescribe a primarily maritime framework for the Strategic Defence Review. The core strategic challenges remain naval ones, yet the Royal Navy has become dangerously weak. Urgent steps must be taken to reverse this trend before it is too late.

The Royal Navy is and remains the principal guardian of the silent principles of UK’s national security, namely preserving the country’s wealth, prosperity and peace, and the free trade global system on which all that depends. However, the Royal Navy is losing coherence. The inexorable downward momentum in the commissioning rate of new surface warships has resulted in a rapidly ageing surface fleet and a reduction of overall fleet utility.

Defenders of the status quo base their arguments on two strong assumptions. The first is that in a globalised and increasingly interdependent world, the powers of multilateral institutions and of supranational jurisdictions will and should wax, as those of the nation state wane.

The second premises is that the utility of ‘hard power’ is being swiftly eclipsed by that of ‘soft power’, such as development aid. This stance has been given material expression in consistent year-on-year real money increases in the budget of the Department for International Development, at the expense of the chronic underfunding of the Ministry of Defence (MoD).

Indeed, the defence budget is in deep trouble. Bernard Gray claims that the real costs of the defence equipment programme are currently £30billion above the present allocated budget in the next ten year period. On top of this, much of the current equipment inventory is being badly over-used and is consequently in increasingly poor repair. The nation is at war in Afghanistan and elsewhere, while a peacetime mentality prevails and Whitehall’s strategic analysis fails to properly understand the risk environment that we are obliged to inhabit.

In practice, globalisation is about the growing interdependence of nations and global regions, but with decreasingly adequate policing of the global commons. Multilateral institutions such as the UN and the EU have been weakened and eroded and they often now act merely as forums within which nations battle nakedly for their national interests. What is needed is a ‘strategic identity review’ and the application of Palmerstonian principles to our alliances in order to ensure that we possess coherent, independent core capabilities to nourish them and to allow them to protect us in return.

The national institution which should translate the national will into this coherent force structure is the Ministry of Defence. In fact the MoD is deeply tribal and, as presently constituted, is simply incapable of solving the major issues of the defence programme. The chiefs of staff are the prime guardians of their own service interests and are seen as such by their personnel, strongly encouraging inter-service rivalry. However, it is an act of self harm for any service to denigrate, and thereby lose, the assistance it needs from the others. It is essential that a full capability approach be taken to the defence programme. Only this will harness capabilities correctly to the full spectrum of first-order national security tasks.

We live now in a time in which wars touch few people directly. Yet, as Trotsky famously remarked, and 9/11 aptly demonstrated: ‘You may not be interested in war, but War is interested in you’. Today, the assumption is that good order is a natural condition and can be taken for granted because ‘nothing happens’. But that ‘nothing happens’ is no accident, but is rather because of pre-emption and deterrence.

The free flow that makes globalised trade and the creation of prosperity possible depends prominently upon the presence of naval units at sea, unseen and silent and therefore easily forgotten. This is the classic operation of deterrence and this silent aspect of national security is of rising importance as the post-Second World War multilateral instruments fade.

The dependence of the West on the use of the sea for its survival and prosperity is a geopolitical fact of life. In particular the dependence of Britain on the secure use of the sea has significantly increased, in both commercial and military operations. According to the Chamber of Shipping, 95 per cent of UK trade by volume and 90 per cent by value is carried by sea. In 2009 total direct employment in UK ports and at sea was over 100,000 people. This is a very substantial industry and a vital one for the well-being of UK citizens. It is an industry that depends on good order at sea and therefore it needs and deserves protection against the increasingly threatening environment in which it must operate.

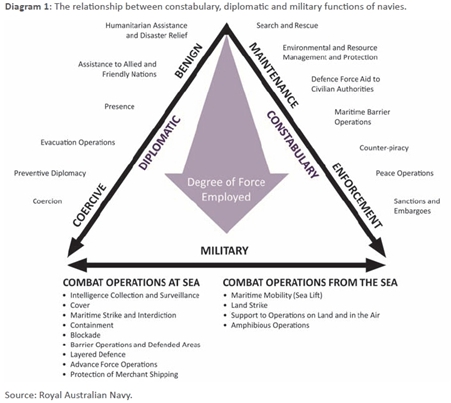

Of course, navies must fulfill a wide range of tasks, summarized in the diagram below (produced by the Australian Navy). Since the end of the Second World War the contention of successive Navy Boards has been that, if a navy of ‘high’ capability is procured, ‘lower’ level tasks (diplomatic and constabulary) will automatically be covered by this ‘consequent capability – the argument of the ‘lesser included’ case. This logic has been used to justify the failure to build new ships and as a case for reducing fleet numbers.

In fact, the evidence shows that the result of this strategy is the opposite of what it intends. The argument for the ‘lesser included’ case is subverted by the high end strategy. Because as well as failing to provide the numbers needed for the ubiquitous maritime security tasks, it also weakens the coherence of the power projection case.

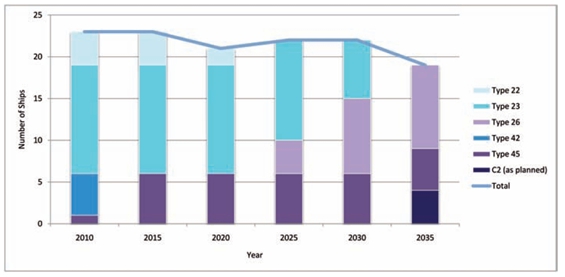

The reduced rate of ship orders means that only sixteen new surface combatants will enter RN service between 2002 and 2031, and the number of significant vessels in the surface fleet will shrink appreciably, as the chart below shows. This rate threatens the viability and skill base of the ship-building industry, plus the manpower base of the Royal Navy, as well as its capability and reach. The average age of our Navy’s surface combatant ships will rise from fifteen years in 2012 to twenty-one years in 2021, with implications for sustainability, support, logistics, cost and viability. Moreover, it contrasts strikingly with countries as varied as Australia, China, India and Japan. Such a programme effectively tells the world that Britain is signing off from serious maritime security – and hence national security.

The profile of significant surface combatant vessels in the Navy, 2010 to 2035 (on pre-cutback plans)

Notes: The ‘Type’ ships are different versions of frigates (20 numbers) and bigger destroyers (40 numbers). ‘C2’ denotes the currently planned two aircraft carriers. The new Type 26 frigate will be of crucial importance.

This picture is an alarming one. Rapid rebuilding of the general purpose fleet is essential for the present and likely core future strategic needs of the UK. Use of the sea demands presence along the sea routes. Presence is the prerequisite for the silent deterrent messages that naval force alone can articulate. Presence demands numbers and we envisage an initial fleet total of around 25 surface combatants. That is, in our judgment, the bare minimum needed for credible conventional deterrence, for power projection, or as a basis for surge construction in the events of another major war. As Frederick the Great observed, ‘diplomacy without force is like music without instruments’.

This blog is a summary of an article first published in the published in the Journal of the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI) on the 23rd of August, 2010.

Click here to leave a comment on this article.

Britain has used the open seas as trade passage, defence and security for centuries.

Britain’s trade wealth depends on the sea, the world depends on The Royal Navy as one of the principal guardians of the open seas and must never be cut or compromised in any way.

For big savings on Defence, we need to give our seat on the security council to the EU, along with our nuclear deterrent. Whilst we retain our seat, we cannot realistically drive front line defence spending much lower. With that seat, we have to have a credible front rank nuclear deterrent. We also have to be able to control our EEZ, trade routes, and have an expeditionary capability of real clout in order to support U.S./U.K./E.U. Foreign Policy objectives. Therefore we need first rate strategic air defence, a permanently available carrier group (therefore 2 carriers) and a deployable armoured division and air portable division. Savings can be made through a long overdue radical reform of the procurement system to instill real commitment to COTS procurement. However savings of the order of 15-20% cannot now be achieved, after a string of previous ‘peace dividend’ cuts, without a comprehensive reappraisal of our global role. Even in this day and age, a major downscaling of that role may well have grave implications for the government that undertakes it.