The UK’s policymaking style since Margaret Thatcher’s premiership has become less deliberative, more frenetic, and significantly more centralised and impositional, argue Patrick Diamond and Jeremy Richardson. This has led to overall weaker governments and worse policy outcomes, but there are ways for the next government to undo the damage of this idiosyncratic policy style.

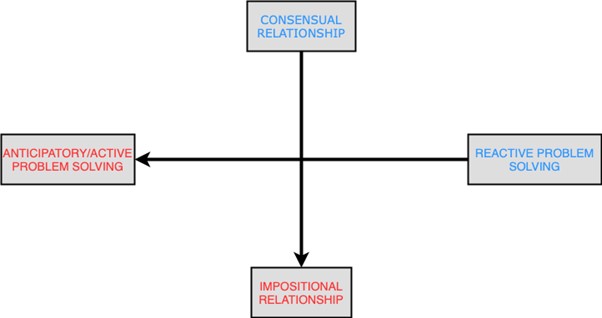

In the original typology of policy styles, the authors considered it useful to analyse the policy process according to two main factors: a government’s general approach to problem solving and its relationship to other actors in the policymaking process. Some governments adopted an anticipatory/active attitude towards addressing social and economic problems, while others pursued an essentially reactive approach. At the same time, some governments sought to work collaboratively with interest groups while others imposed decisions from the centre. A nation’s policy style was defined as the interaction between these two dimensions: the overall approach to problem solving and the extent of collaboration with outside interest groups. Following this typology, in recent years the process of making public policy in Britain and many other liberal democracies has become markedly less deliberative, much more frenetic, and significantly more impositional, resulting in weaker government and worse policy outcomes.

Post-war policy styles 1945-1970s

Source: Jeremy Richardson, Policy Styles in Western Europe, (Routledge Revivals, 1982)

For much of the post-World War II period until Margaret Thatcher’s election in 1979, Britain could be characterised as having a policy style which placed particular emphasis on bargaining with interest groups, while granting civil servants a major role in the development of public policy.

The concept of national policy style

In the past, Western European democracies were believed to place great emphasis on consensual and bargaining relationships with interest groups (via close collaboration between those groups and civil servants, often labelled “bureaucratic governance”). Some governments combined that feature with anticipatory policymaking, others with a mainly reactive approach. For much of the post-World War II period until Margaret Thatcher’s election in 1979, Britain could be characterised as having a policy style which placed particular emphasis on bargaining with interest groups, while granting civil servants a major role in the development of public policy in the context of a reactive approach to problem solving. Mrs Thatcher then altered the policymaking process in two key respects. First, the central state became more assertive and impositional. Secondly, as Prime Minister, Thatcher was adept at “handbagging” interest groups who were perceived to be an obstacle to reform, notably the British trade unions in the wake of the so-called Winter of Discontent in 1978-79.

The evidence indicates that the process of making public policy in the UK in particular has become markedly less deliberative, much more frenetic, and significantly more impositional.

Tectonic shifts in policy styles

Since the very concept of a policy style was first articulated in 1982, the process of policymaking has been reshaped by tectonic forces, all of which have reduced the capacity to devise well thought-out and effective public policies in many advanced economies. For example, the task of anticipatory policymaking appears increasingly problematic for many governments. Their inability to devise policies that can address the growing threat of climate change is perhaps the most egregious example, matched closely by the failure to plan for an inevitable pandemic and public health emergency. The evidence indicates that the process of making public policy in the UK in particular has become markedly less deliberative, much more frenetic, and significantly more impositional.

Alongside these trends, the power relationship between traditional policy actors has been significantly altered. The shift towards a more impositional policy style has further diminished the role of interest groups, while the trend towards a politicised management style has weakened the influence of career civil servants in the policy process. These changes have actually negated the efficacy of policy expertise available to Ministers, in particular by depleting governments of institutional memory and codified knowledge.

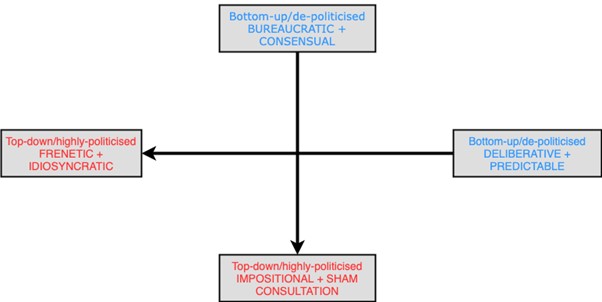

Policy styles 1980s to the present

Source: Jeremy Richardson, The study of policy style: reflections on a simple idea, in Political Science and Public Policy, 2022

Britain as a prime example of idiosyncratic governance?

We all got used to logging on to CNN during Donald Trump’s Presidency. The daily excitement of “what will happen next?” became almost addictive. Trump’s approach to governing in the United States was impossible to predict. It was idiosyncratic governance writ large. There were almost no “standard operating procedures” to keep the ship of state on an even keel, let alone to follow a steady course or consistent governing strategy. After a period of repeated turbulence, it is time to ask if Britain has gradually evolved a dual policy style which now has the rest of the world logging on to the BBC wondering: “What will happen next? Who will be Prime Minister this morning?”

At the head of the creaking government machinery, Britain has seen the emergence of an unstable, often idiosyncratic political class.

There has been a great deal of interest in whether UK policymaking is now more prone to systemic failure, highlighted a decade ago by the publication of Anthony King and Ivor Crewe’s well known treatise, The Blunders of Our Governments. King and Crewe tell the story of Britain’s policy omnishambles in a highly entertaining way, although they focus less on explaining why Britain has become pecularly vulnerable to policy fiascos.

The root causes of the omnishambles policy style that now characterises UK policymaking is the changing relationship between Ministers and civil servants. The popular TV series, Yes, Minister, was a programme broadcast in the 1970s that cast civil servants as cunning, wily manipulators of Ministers. A more recent satire, The Thick of It, focuses on the role of devious “special” advisers who ruthlessly side-line permanent bureaucrats. This shift in the popular depiction of government underlines how the tables have turned. Once upon a time, civil service “mandarins” were believed to ultimately control the policy process. Now, it is Ministers and their political advisers who dominate the Whitehall machine. Officials have apparently been too cowed to “speak truth to power”. They are increasingly afraid to challenge their political masters or to think for themselves.

This major shift in how public policy is formulated has occurred alongside other troubling developments. At the head of the creaking government machinery, Britain has seen the emergence of an unstable, often idiosyncratic political class. As the COVID Inquiry laid bare, the British political elite was self-evidently not up to the task of managing a major health crisis. The Cabinet Secretary and Britain’s top civil servant, Simon Case, observed that the former Prime Minister Boris Johnson “changed strategic course every day” during the pandemic. “He cannot lead” was Case’s damning verdict to the inquiry.

Events since COVID have re-enforced that depressing story of a nation’s political system in marked decline. Over the course of the 44-day premiership of Liz Truss, the UK government discarded its historical reputation for fiscal probity leading to a huge rise in long-term borrowing costs. Much has been written recently about the failure of Britain’s public institutions. Even the once beloved Post Office is demonstrably dysfunctional. As the Post Office saga illustrates, institutions are run by people at the top. If those people are not up to it, things go very badly wrong, as we saw during the Truss Premiership. Taking stock of the Sunak Government’s recent Budget statement, the veteran FT commentator Martin Wolf concluded: “The British policy process and the institutions in charge of it are broken”.

The absence of a serious, long-term plan to address the economic challenges bedevilling the UK is palpable. A recent Institute for Government report concluded:

“While the UK has a complex network of political checks and balances, we believe that recent events have shown that these checks and balances are not robust enough. In the UK system, a government commanding a majority in the House of Commons faces few legal constraints, and has regularly been able to evade or ignore the political checks that exist within parliament and beyond.”

These fundamental problems are compounded by the fact that relatively few Government Bills are now subject to Pre-Legislative Scrutiny, while Ministers have increasingly resorted to emergency fast tracking of legislation. There is greater use of Statutory Instruments, while at the same time an even greater volume of legislation is being introduced. No wonder that frenetic legislative style produces policies that are widely judged to be ineffective.

The emphasis on the top-down imposition of highly politicised policy initiatives from the centre has paradoxically made British government weaker, and paradoxically made it harder for Ministers to achieve their goals.

Britain in recent decades has forged a unique omnishambolic policy style: an amalgam of top-down/highly politicised, frenetic and idiosyncratic governance, alongside top-down/highly politicised, impositional and sham policy consultation. The emphasis on the top-down imposition of highly politicised policy initiatives from the centre has paradoxically made British government weaker, and paradoxically made it harder for Ministers to achieve their goals.

The disorderly and chaotic inheritance that is bequeathed to a new government will not be easily rectified, and unravelling this tangled thicket of a dysfunctional policymaking system will not be straightforward for incoming Ministers. However, the system is not incapable of improvement. A new Prime Minister has to increase civil service confidence by restoring basic proprieties, such as not interfering in the recruitment process for permanent senior officials. There should be a particular emphasis on investing in the policymaking capacities of the civil service, and rebuilding the status of the policy professions within Whitehall departments.

Devolving power is necessary not only to give more control to local areas, but to strengthen the capacity of central government to discharge the responsibilities only it can adequately fulfil.

Ministers must also encourage the civil service to look outwards. There should be a collective effort to involve interest groups and external stakeholders more actively throughout the policymaking process. Departments invariably rely on the embedded knowledge within policy communities and networks. But most fundamentally of all, the centre of government should seek to do less but do it better. There are large swathes of public policy that should be devolved to sub-regional institutions in England, advancing the experiment in city-region devolution initiated over the last decade. Devolving power is necessary not only to give more control to local areas, but to strengthen the capacity of central government to discharge the responsibilities only it can adequately fulfil.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Image credit: Andy Wasley on Shutterstock