In the wake of the economic crisis and Great Recession, there has been much talk of spatial re-balancing the UK economy from South to North. The ‘re-balancing’ mantra is far from new, however; the British economy has long been skewed towards London and the surrounding South East region and. In a recent paper, Ron Martin, Ben Gardiner, Peter Sunley and Peter Tyler document how the degree of spatial imbalance in Britain’s economy is both real and has continued to widen. However, the various policy measures introduced over the past three years or so do not add up to a coherent and effective response. The solution to the problem will require addressing the fundamental constraints preventing the re-balancing of the United Kingdom – both sectorally and spatially.

A major economic recession inevitably provokes a search for causes and explanations, as well as a rethink of policy agendas and models. One of the key issues that surfaced in the wake of the financial crisis and ensuing recession was a political recognition that the UK’s economy has become too spatially unbalanced. This was a central theme of prime minister David Cameron’s first major speech following the election of the coalition government:

Today, Britain is at a turning point. For many years we have been heading in the wrong direction… Today our economy is heavily reliant on just a few industries and a few regions – particularly London and the South East. This really matters. An economy with such a narrow foundation for growth is fundamentally unstable and wasteful – because we are not making use of the talent out there in all parts of our United Kingdom. We are determined that should change. (David Cameron, 28 May, 2010)

Promoting a more spatially even distribution of economic growth has thus figured prominently in government’s new mantra of ‘rebalancing’ the economy. Yet this issue of spatial imbalance is hardly new. The British economy has long been skewed towards London and the surrounding South East region. Even during the last quarter of the 19th century these were the fastest growing areas of the UK by some margin. And during the inter-war years, London and the South East led the emergence of the new industries of the period, together accounting for some 70 per cent of all new manufacturing firms, while much of northern Britain suffered the structural collapse of its older, Victorian industrial base. This growing spatial imbalance was the central theme of the famous Barlow Commission Report (1940), which was quite emphatic in its message:

The contribution in one area of such a large proportion of the national population as is contained in Greater London, and the attraction to the Metropolis of the best industrial, financial, commercial and general ability, represents a serious drain on the rest of the country. (Royal Commission on the Distribution of the Industrial Population, para. 171)

Barlow’s Report was to form the foundation of post-war regional policy, designed to redress this spatial imbalance. But the problem resurfaced again in the 1980s, this time in the guise of a widening of a ‘North-South divide’. The degree of spatial imbalance in Britain’s economy is both real and has continued to widen.

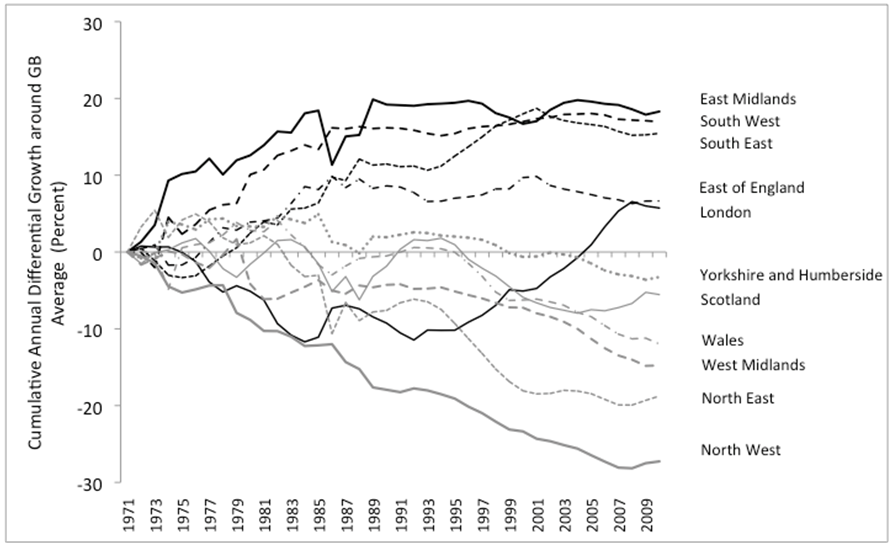

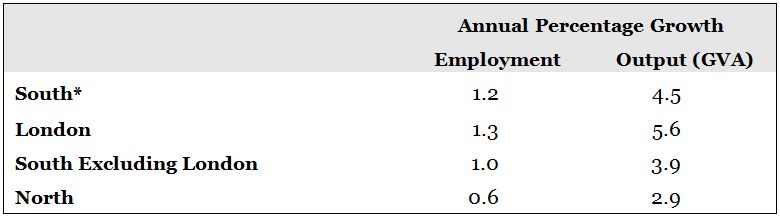

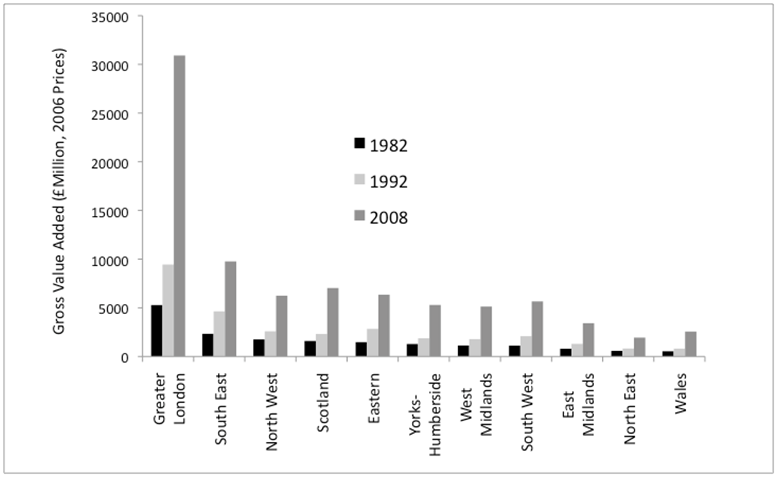

As we document in our recent paper, the period since the early-1990s has witnessed two significant developments. First, a dramatic improvement in London’s growth performance; and second, a progressive falling behind in growth of much of regional Britain north of a line from the Wash to the Severn (see Figure 1). During the 1970s and much of the 1980s, London actually grew more slowly, in output terms, than almost all of the rest of Britain: in this respect it resembled the North than the rest of the South. But from around the mid-1980s, having lost much of its former manufacturing industrial base, and with the financial deregulation and liberalization of ‘Big Bang’ in 1986, its economic fortunes subsequently underwent a dramatic turnaround, and during the ‘longest boom’ in the country’s history, it was by far the fastest growing part of the national economy, and propelled the superior growth of the South as a whole (see Table 1). The bulk of London’s output growth came from finance, banking, insurance and related services, and the capital dominates this sector of the economy (see Figure 2). Just as London and the South East captured much of the ‘new economy’ of mass consumer goods industries in the 1920s and 1930s, so in the 1990s and 2000s these areas triumphed in the extraordinary growth of the new ‘finance-led economy’, or rather what proved to be an unstable and unsustainable financial bubble.

Figure 1: Cumulative Regional Output Gaps, 1971-2010

Note: The figure shows the year on year cumulative difference between a region’s annual percentage growth of GDP and the corresponding rate for the British economy as a whole

Source: Gardiner, Martin, Sunley and Tyler (2013)

Table 1: How London’s Economy Led the 1992-2007 ‘Long Boom’

Note: * South includes: London, South East, East of England, South West and East Midlands. North includes; West Midlands, Yorkshire-Humberside, North West, North West, Wales, Scotland.

Source: Gardiner, Martin, Sunley and Tyler (2013)

So the government is right to call for a more geographically balanced economy. But do the various policy measures introduced over the past three years or so add up to a coherent and effective response? We fear not. The government wants the economy to ‘start making things’ again, but the measures to ‘reindustrialise’ Britain are likely to be too little, too late. For decades, successive governments (and the City of London) have neglected manufacturing, and, unlike for example in Germany, have been reluctant to nurture, and invest in this sector. Despite the government’s claims, its various new initiatives (for example, the Regional Growth Fund, measures to support small firms, the establishment of new technology centres and the new City Deals), while all worthy and welcome, unfortunately do not add up to a coherent and sufficiently funded and committed ‘strategy for growth’. This was recognized of course by Lord Heseltine in his bold proposals for devolving some £50 billion of public expenditure annually to the regions and cities outside London (proposals that incidentally echo his complaint in the 1980s that the sums devoted to regional assistance to the less prosperous areas of the country were dwarfed by London’s and the South’s share of public expenditure – what he called ‘counter-regional ‘policies). Although his proposals ostensibly met with approval by Chancellor George Osborne, it looks as if the actual sums to be devolved will be much smaller than Lord Heseltine recommended, a mere £2 billion: the Treasury has always been protective of its hold on the public purse strings.

Figure 2: London’s Dominance in the Growth of Output in Finance and Banking, 1982-2008

Source: Gardiner, Martin, Sunley and Tyler (2013)

The fact that after nearly ninety years of regional policy Britain’s economy is still spatially divided between South and North suggests that the problem is a systemic one, requiring a systemic solution. It is often claimed that the success of London and the South East is merely testament to the ‘natural workings’ of the market. Some take this argument further and suggest that we should encourage economic activity and workers to abandon northern towns and cities and move to the South to maximize growth there. Such pronouncements fail to acknowledge the reality that the economies of London and the South East are not simply driven by market forces, but also heavily underwritten by the State; that this apart of the country enjoys preferential access to finance; that it is able to exert a disproportionate influence on government economic policy; and that in London it has a city which has a degree of political and economic autonomy not found in other UK cities. Moreover, recent debates on regional policy have been hamstrung by a mistaken belief that the economies of London and the regions are essentially in a zero-sum competitive game, so that any moves to support the North’s cities and economies are far too easily dismissed as harmful to London. We agree with David Cameron that an economy so reliant on London and the South East is both wasteful and unstable. But the solution to the problem will require much more than small-scale discretionary measures that do very little to change the fundamental constraints preventing the re-balancing of the United Kingdom – both sectorally and spatially.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

Ron Martin FBA is Professor of Economic Geography at Cambridge University. His research interests include the geography of labour markets, regional growth and development, the geographies of money and finance, and evolutionary economic geography. He has published some 30 books and more than 200 papers on these and related themes. In 2003 he was included in the American Economic Association’s list of most cited economists. In 2005 he was elected a Fellow of the British Academy for his contributions to economic geography. He is a co-founder of the Cambridge Centre for Geographical Economic Research and a founder editor of the Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society. He is currently engaged on an ESRC project on regional economic resilience to recessions. He was recently appointed to the Lead Expert Group on the UK Government Office for Science’s major new Foresight project on the Future of Cities.

Ron Martin FBA is Professor of Economic Geography at Cambridge University. His research interests include the geography of labour markets, regional growth and development, the geographies of money and finance, and evolutionary economic geography. He has published some 30 books and more than 200 papers on these and related themes. In 2003 he was included in the American Economic Association’s list of most cited economists. In 2005 he was elected a Fellow of the British Academy for his contributions to economic geography. He is a co-founder of the Cambridge Centre for Geographical Economic Research and a founder editor of the Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society. He is currently engaged on an ESRC project on regional economic resilience to recessions. He was recently appointed to the Lead Expert Group on the UK Government Office for Science’s major new Foresight project on the Future of Cities.

Ben Gardiner is a director of Cambridge Econometrics and a research associate in the Department of Geography at Cambridge University. His work at Cambridge Econometrics includes regional and sectoral projects, and econometrics training. Within Cambridge University he is researching UK regional resilience with Ron Martin and Pete Tyler, and he is also working on a part-time PhD on the resilience of Europe’s regions. Until recently he was on a two-year leave of absence working as a senior scientist for the European Commission (JRC-IPTS) on regional economic modeling.

Ben Gardiner is a director of Cambridge Econometrics and a research associate in the Department of Geography at Cambridge University. His work at Cambridge Econometrics includes regional and sectoral projects, and econometrics training. Within Cambridge University he is researching UK regional resilience with Ron Martin and Pete Tyler, and he is also working on a part-time PhD on the resilience of Europe’s regions. Until recently he was on a two-year leave of absence working as a senior scientist for the European Commission (JRC-IPTS) on regional economic modeling.

Peter Sunley is Professor of Economic geography at the University of Southampton. His research has focused on the geographies of labour organisation and welfare policy, regional development, innovation and venture capital, the geography of the design and creative industries, and evolutionary economic geography. He has published extensively with Ron Martin across several of these areas, including clusters, regional competitiveness and regional path dependence. He recently completed research projects on the geography of the design industry in the UK, and the financing of social enterprise. He is currently working with Ron Martin, Peter Tyler and Ben Gardiner on an ESRC project on the regional economic resilience to recessions

Peter Sunley is Professor of Economic geography at the University of Southampton. His research has focused on the geographies of labour organisation and welfare policy, regional development, innovation and venture capital, the geography of the design and creative industries, and evolutionary economic geography. He has published extensively with Ron Martin across several of these areas, including clusters, regional competitiveness and regional path dependence. He recently completed research projects on the geography of the design industry in the UK, and the financing of social enterprise. He is currently working with Ron Martin, Peter Tyler and Ben Gardiner on an ESRC project on the regional economic resilience to recessions

Pete Tyler is a Professor in urban and regional economics in the Department of Land Economy, University of Cambridge. He has an extensive track record in undertaking research in urban and regional economics with a particular emphasis on the evaluation of policy. He has been a Project Director for over seventy major research projects for the UK Government, resulting in the publication of forty research monographs. He is a co-founder of the Cambridge Centre for Geographical Economic Research and a founder editor of the Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society.He is currently investigating the long-term dynamics of interdependent infrastructure systems being as part of a team funded by the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) and has recently begun a major research project with Ron Martin for the ESRC on regional economic resilience to recessions.

Pete Tyler is a Professor in urban and regional economics in the Department of Land Economy, University of Cambridge. He has an extensive track record in undertaking research in urban and regional economics with a particular emphasis on the evaluation of policy. He has been a Project Director for over seventy major research projects for the UK Government, resulting in the publication of forty research monographs. He is a co-founder of the Cambridge Centre for Geographical Economic Research and a founder editor of the Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society.He is currently investigating the long-term dynamics of interdependent infrastructure systems being as part of a team funded by the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) and has recently begun a major research project with Ron Martin for the ESRC on regional economic resilience to recessions.

9 Comments