The proportion of women elected to parliament in the UK remains low compared to other countries. In this post, Chris Terry examines the gender balance of parliamentary candidates for the upcoming election, and concludes that some progress is being made. Nevertheless, he suggests switching to a system of proportional representation would increase the descriptive representation of women faster than is likely under the current first-past-the-post system.

The importance of women’s representation in parliament should not be underestimated. That only 22.8% of our MPs are women is a shocking underrepresentation of half the British electorate. To function best, parliament needs the widest possible set of experiences from its representatives.

In the league table of women’s representation in parliaments, the UK languishes at a slightly embarrassing 56th out of 141 – below states such as Rwanda, Nicaragua, Algeria and Kyrgyzstan.

At the Electoral Reform Society our Women in Westminster report looked into how many women might be elected after the election, by modelling likely results. We found a likely rise after the next election to 29.5% women, which would put the UK up to a less embarrassing 36th. Yet progress remains slow.

For women to be elected to the Commons they must be selected by political parties. If a constituency is presented with no women candidates, then obviously it cannot possibly elect one. So the selection of women candidates by parties is of vital importance.

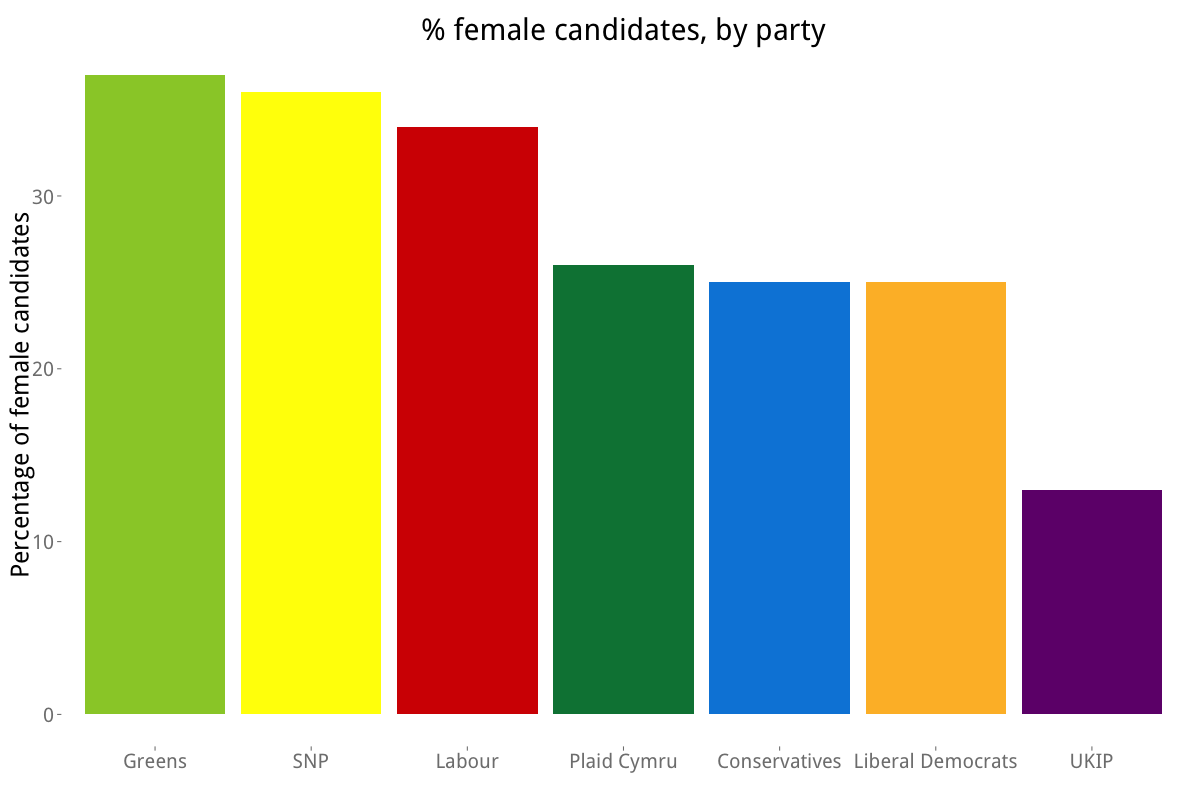

The Greens have selected the largest number of women candidates, though amongst the parties likely to win substantial numbers of seats, the SNP and Labour have the best record.

Yet, in order for there to actually be women MPs these women must be elected. In order to be elected they need to be in winnable positions. Women candidates deployed in seats certain to be won by male candidates from other parties will result in no further advance in women’s representation.

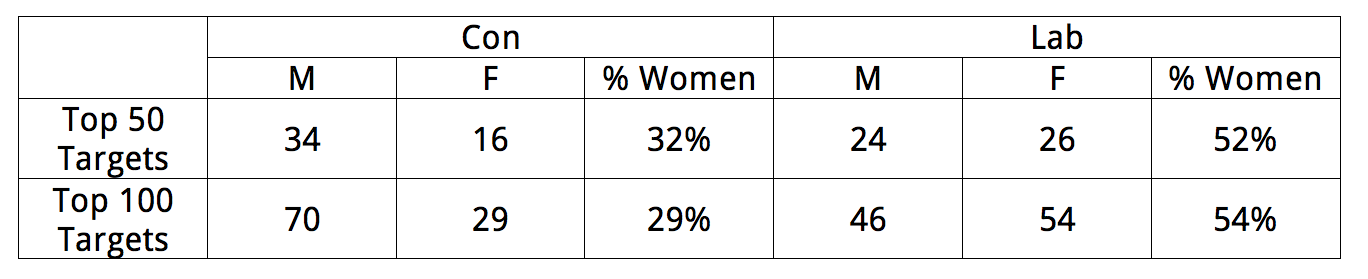

In target seats for the main two parties the story is positive, especially on the Labour side, with a majority of women selected in the party’s top 50 and top 100 targets.

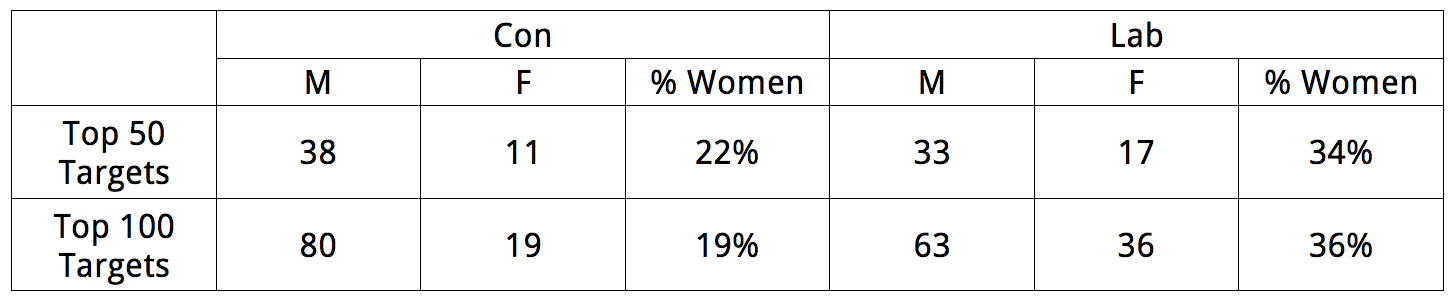

However, when we look at safe seats the story is less positive.

Here the problem is incumbency. Once an MP is in a seat, they are difficult to deselect. And because our archaic voting system tends towards the creation of safe seats, there are a lot of places where incumbents stay in position for a long time.

Our report shows that of the 312 incumbents standing for election this year who were originally elected in 2005 or earlier, only 18.3% are women. Of the 67 incumbents elected before 1992 and standing again this year, just 11.9% are female.

These figures reflect a major reason for parliament’s continued male dominance. Women can only be elected in new gains or in seats where they replace retiring incumbents. However, there are only so many of these seats, and many continue to be held by men selected long ago. Hence large portions of parliament whose MPs were selected in less representative times for women remain essentially blocked until those MPs decide to retire.

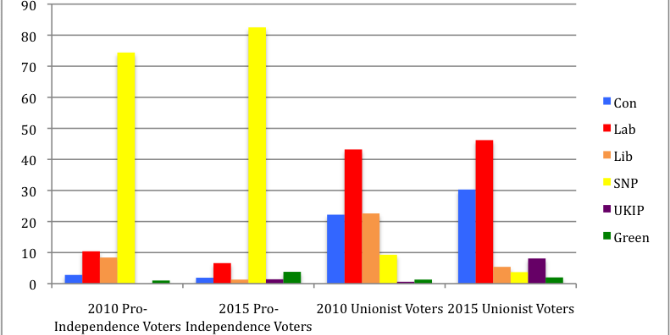

This partly explains why Britain ranks so lowly. Countries with more proportional electoral systems tend to have superior gender representation.

Proportional systems also tend to avoid the situation amongst selectors where they can sometimes seek to select candidates who most look like their mental image of an MP – generally, male. In a multi-member constituency, parties tend to select a more diverse slate of candidates in order to appeal to the widest possible range of electors. Proportional representation also gives parties a larger range of options in terms of how they go about getting gender representation, with methods such as zipping or party internal gender quotas in selections.

Yet while Britain’s First Past the Post acts against the representation of women, the fact that the number of women candidates is going up and that the ERS are able to project a rise in women does show that parties can move forwards in this area. A change to a proportional system would make it easier for parties to improve gender representation, but that cannot be done in isolation.

Parties can and should work to guarantee better gender representation into the next parliament and beyond.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the General election blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

Chris Terry is a Research Officer at the Electoral Reform Society

Chris Terry is a Research Officer at the Electoral Reform Society

First Past the Post will cause some bizarre results in the forthcoming May General Election. I hope this will stimulate electoral reform. However consider this:

‘First Past the Post’ could be easily modified to achieve Gender balance without women short lists, quotas, or any form of sex discrimination by treating men and women equally but separately, as follows.

In the General Election each party is allowed (but not forced) to put forward one male candidate and one female candidate in each constituency.

Voters have two ballot papers – one with all the male candidates, one with all the female candidates.

Each voter has one vote on each ballot paper.

One candidate, the one with the most votes, regardless of which ballot paper they are on, is elected.

There would be strong incentive for parties to put forward one male and one female candidate because this system favours the candidates (of whichever sex) on the ballot paper with the fewest candidates.

An election using this system would result in a significant change to the gender balance, without coercion or discrimination, and it is self correcting.

Personally I would hope the new generation of MPs would then bring in a system of similarly modified proportional representation.

I would be happy to receive criticism of this proposal both from a Political Science and a Gender Politics perspective.