More than ten years later, it is clear that the British public have doubts about the objectives and success of the lengthy and often controversial Iraq and Afghanistan missions. Evident confusion, cynicism and doubts over the truthfulness of government sources regarding the purposes of past military action may have potential implications for the viability of UK involvement in future missions if these uncertainties and suspicions become embedded in the public mind, write Rachael Gribble and colleagues.

The public’s support of military action plays an important role in defence and foreign policy, from establishing the political legitimacy of missions to maintaining military effectiveness and helping justify defence budgets. While there has been widespread debate about what the British public thinks of the missions in Iraq and Afghanistan over the last decade, robust academic evidence on this is lacking. Most data on British public opinion in this area have been collected via opinion polls, which provide quick and timely evidence on public perceptions but can have potential drawbacks, such as the representativeness of the final sample. UK research is also lacking in relation to the British public’s estimation of military casualties. The accuracy of these estimations can indicate levels of public attention to, or understanding of, events during military missions.

To address these issues, we used data from over 3,000 people who took part in the 2011 British Social Attitudes (BSA) survey. The BSA is an annual look at public opinion in a range of different policy areas using a representative sample of adults aged 18 years and over from England, Scotland and Wales. Participants were randomly allocated at interview into two groups to answer questions on either the Iraq or the Afghanistan mission.

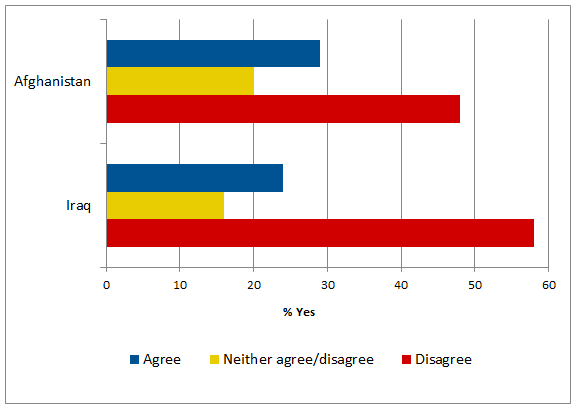

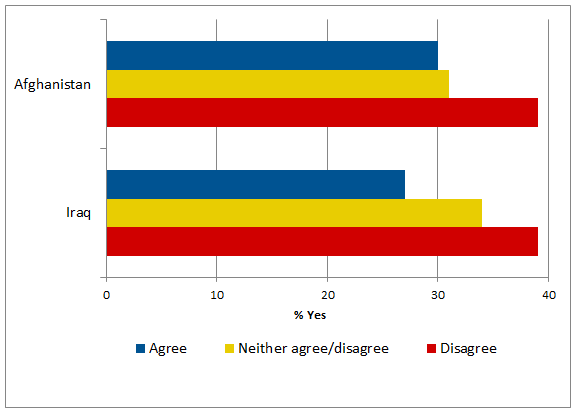

Overall, our findings show that British public opinion of both the Iraq and Afghanistan missions were largely negative. Earlier research we conducted using the same data showed that one in five disagreed with UK involvement in each of these missions. These opinions differed according to which campaign the public were asked about, with Afghanistan viewed more positively than Iraq. While 58 per cent disagreed with UK involvement in the Iraq mission, 48 per cent disagreed with Afghanistan (see Figure 1). This study found that, along with public disagreement with the missions, less than a third of the public saw either as achieving success, although Afghanistan was believed to be more successful than Iraq (see Figure 2). This divergence in opinion between the Iraq and Afghanistan missions has been seen in public perceptions in other countries and is related to differences in the justifications and circumstances of the two campaigns. So what do the British public think were the reasons behind Iraq and Afghanistan?

Figure 1: Public approval of the Iraq and Afghanistan missions

Figure 2: Public perceptions of the success of the missions

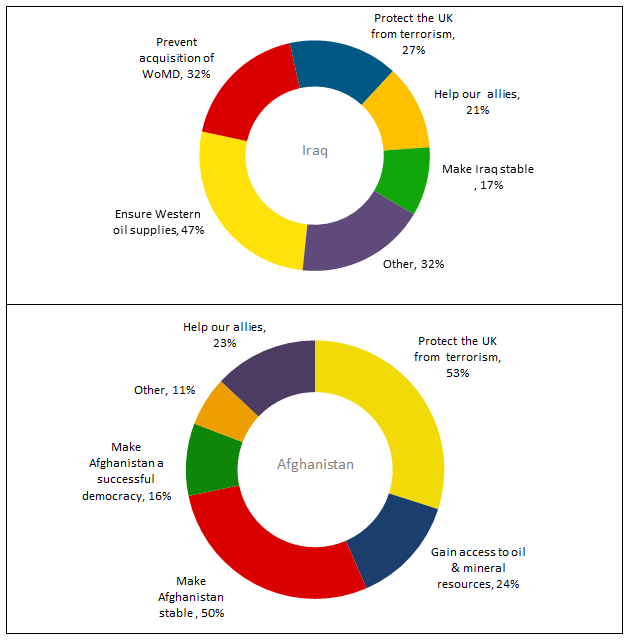

Public perceptions of the reasons behind the missions showed evidence of cynicism, particularly in relation to the Iraq mission. The mostly commonly cited reason for this campaign, ensuring Western oil supplies (Figure 3), did not match any of the official aims (preventing the acquisition of weapons of mass destruction, democratisation and preventing terrorism). The cynicism about Iraq is likely to be linked to the “war-for-oil” narrative that has gained traction in some mainstream media sources, and fuelled by the general distrust of the motives of the government of the time following the exposure of the ‘dodgy dossier’ regarding Saddam Hussein’s possession of weapons of mass destruction. Given the popularity of the “war-for-oil” narrative, it is perhaps not surprising to see it reflected in public responses regarding the reasons for the Iraq mission, although it is interesting to see it cited as the most common one.

Figure 3: Public perceptions of the purposes of the Iraq and Afghanistan missions

Public doubts about the motives for UK involvement in Iraq appear to have had some influence on opinions about Afghanistan. Most of the public endorsed the official objectives in relation to UK involvement (preventing terrorism and creating stability) as communicated by the government and the media during the lead-up to UK involvement (Figure 3), but almost a quarter of responses suggested that gaining access to oil and mineral resources was a reason for UK involvement despite such factors never being mentioned in any official communications about the mission.

As well as opinions of the missions, we looked at estimates of military casualties. Increased public attention to media coverage of military casualties is known to be a major predictor of whether people can accurately estimate the number of military deaths and injuries. Despite the intensive media coverage of both campaigns, we found that less than a quarter of the public could accurately estimate the number of UK military fatalities. Again, there were differences between the missions. The Afghanistan survey group were more likely to under-estimate the number of military deaths than the Iraq survey group.

This difference between the missions was somewhat surprising. It cannot be attributed to a lack of information, as both missions were similar in terms of public interest and information about their progress was readily available. The level of inaccurate estimates might indicate poor attention towards or understanding of events during the mission amongst the British public or a lack of public interest in the campaigns, possibly due to mission fatigue. Alternatively, as operations in both theatres occurred simultaneously for much of their duration, the public may have conflated the events of the missions, resulting in public perceptions of the number of fatalities being roughly equal between the two actual figures.

Another possibility is that the improved accuracy in the Afghanistan group might be explained by more favourable attitudes towards military missions, with those with higher public support receiving greater public understanding and attention. We have confirmed that the British public is less disapproving of UK involvement in Afghanistan and are more likely to think it is successful compared to the Iraq mission. When we looked at approval and accuracy of estimation, we found that people who disagreed with the missions were more likely to over-estimate the number of military deaths, probably as a result of their disapproval of the missions as a whole resulting in an over-estimation of the costs, including human fatalities, involved. People who agree with military action may, conversely, be more likely to under-estimate the costs involved.

Perceptions of why the UK became involved also appeared to affect casualty estimation. Those who were the most cynical about the purposes of the missions, endorsing war-for-oil (Iraq) or terrorism (Afghanistan) narratives, were the most able to accurately estimate the number of UK military fatalities. This is perhaps explained by the fact that those most likely to endorse the war-for-oil narrative for the Iraq mission are those who are more likely to be engaged with current affairs media (men and those with higher educational levels) and therefore be more likely to access any available information about Iraq and Afghanistan.

What do these findings mean?

More than ten years later, it appears that the British public have doubts about the objectives and success of the lengthy and often controversial Iraq and Afghanistan missions. Evident confusion, cynicism and doubts over the truthfulness of government sources regarding the purposes of past military action may have potential implications for the viability of UK involvement in future missions if these uncertainties and suspicions become embedded in the public mind. One of the most important legacies stemming from the Iraq and Afghanistan missions may be the power of public opinion to potentially restrict future foreign policy, with obvious long-term implications for the future security of the UK.

This reluctance among the British public to support certain types of military interventions has already been seen in the caution exhibited regarding the proposed military interventions post-Iraq/Afghanistan in Mali, Libya and in the on-going debates about intervention in Syria and missions against the Islamic State. Such aversion may lead to an increased examination of how the UK’s military forces are utilised in international crises, especially those requiring a commitment to ‘boots on the ground’. Stronger evidence may be needed to gain public approval for any potential involvement in military action, particularly among groups especially sceptical about Iraq and Afghanistan. Additionally, in cases where the reasons behind a mission are viewed by the public as being irrelevant or ambiguous, there may be reduced support, particularly if there is a perception that this may result in another prolonged and costly campaign.

How long current public caution about military intervention might last, and how strong its effects on foreign policy, are important questions, as is how public opinion might change in response to government efforts to improve public support of its international policies. Much will depend on the extent to which threats are perceived as serious and as threatening to UK territory and vital interests, by both the government and the British public.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting. Featured image credit: Mike Rushmore CC BY-SA 2.0

Rachael Gribble is a PhD student in the Centre for Military Health Research, King’s College London.

Rachael Gribble is a PhD student in the Centre for Military Health Research, King’s College London.

Sir Simon Wessely is Professor and Head of the Department of Psychological Medicine and Vice Dean for Academic Psychiatry at the Institute of Psychiatry (IoP), King’s College London.

Sir Simon Wessely is Professor and Head of the Department of Psychological Medicine and Vice Dean for Academic Psychiatry at the Institute of Psychiatry (IoP), King’s College London.

Susan Klein is Professor in the Institute for Health and Wellbeing Research at Robert Gordon University.

Susan Klein is Professor in the Institute for Health and Wellbeing Research at Robert Gordon University.

David Alexander is Professor at Robert Gordon University and Director of the Aberdeen Centre for Trauma Research.

Christopher Dandeker is Professor of Military Sociology in the Department of War Studies, King’s College London.

Christopher Dandeker is Professor of Military Sociology in the Department of War Studies, King’s College London.

Nicola Fear is Professor of Epidemiology and Director of the Centre for Military Health Research, King’s College London.

Nicola Fear is Professor of Epidemiology and Director of the Centre for Military Health Research, King’s College London.

Dear authors,

Interesting article, valuable findings, and very important! I would recommend it to policy makers and it is very useful for research.

For the sake of continuing the debate, three points of criticism:

1. The article implicitly suggests that there has been a decline of public support (“more than ten years late…”), but while these findings are valuable, they only say something about the current state of affairs and nothing more. Without any similar evidence of previous opinion surveys, it cannot be excluded that public support for these missions have been stable or even increased. We know we can be quite sure that is probably not the case, but the evidence lacks. So it needs to be emphasised here that this is a snapshot – an important snap-shot – which does not say anything about public opinion on longer terms.

2. The last paragraph may be the most important. Public opinion is not static and in constant flux. Government rhetoric and strategic narratives matter, they are not windsocks to public opinion but can influence the public’s view and perception by explaining and providing answers to the strategic ‘why’, ‘wherefore’ and ‘how’ questions.

3. I personally disagree with the idea that the number of casualties predicts public support. I think that is not an independent variable but should be judged in conjunction with other factors such as, the nation’s interest at stake, the strategy, expectations of success, legitimacy and justification, the government’s narratives and several other factors that have been explored in numerous scholarly work (see for example Klarevas 2002). So in short, a more nuanced view is needed here.

Other than that, I think this is a valuable addition in the literature on the UKs involvement in Iraq and Afghanistan. Hopefully, the research will be done again in order to draw some conclusions over similarities / difference over time.