Drawing on cross-national surveys, Ben Clements explains that in recent years the British have expressed high levels of positive sentiment towards the American people, they have been well-disposed towards the US as a country, but have been markedly negative about Trump’s presidency and policies.

Drawing on cross-national surveys, Ben Clements explains that in recent years the British have expressed high levels of positive sentiment towards the American people, they have been well-disposed towards the US as a country, but have been markedly negative about Trump’s presidency and policies.

The Trump presidency and its promotion of the ‘America First’ agenda, as well as the prospect of Britain leaving the EU, has generated renewed debate over the nature of political, military, and economic relations between the US and UK. Trump’s visit to the UK in 2018 engendered large-scale protests while Jeremy Corbyn has been distinctly cooler than Theresa May about the merits of close relations between the two countries. The political and personal relationships between prime ministers and presidents have clearly been very important for post-war British foreign policy, though the health of transatlantic relations has fluctuated over time.

The broader structure of UK-US relations has been compared to a ‘layer-cake’, ‘with personal leader relations at its apex, bureaucratic interweaving in the middle, and public-level cultural interaction at its base’. It has therefore been suggested that post-war British foreign policy observed that UK-US relations could be analysed at three levels: firstly, the political leadership; secondly, that of officials; and thirdly, the general public. An early-1990s study of the British foreign policy elite found that 80% perceived that there was a special relationship – just 5% said Britain had never enjoyed such a relationship; moreover, 91% agreed that the transatlantic connection was crucial or very important to the UK’s international role and interests. A YouGov poll conducted in 2016 showed that 57% of opinion-formers maintained there was still a special relationship, while 37% held the opposite view (only 5% said there had never been such a relationship).

In research on British public opinion towards the US in the 1970s-80s, Crewe noted ‘general attitudes of liking and trust are positive’ which became ‘lukewarm when directed to the performance and judgement of the United States government and of particular presidents’. Is this broad distinction still a feature of British public opinion? What have been the views of the British public towards USA and its presidents in recent decades?

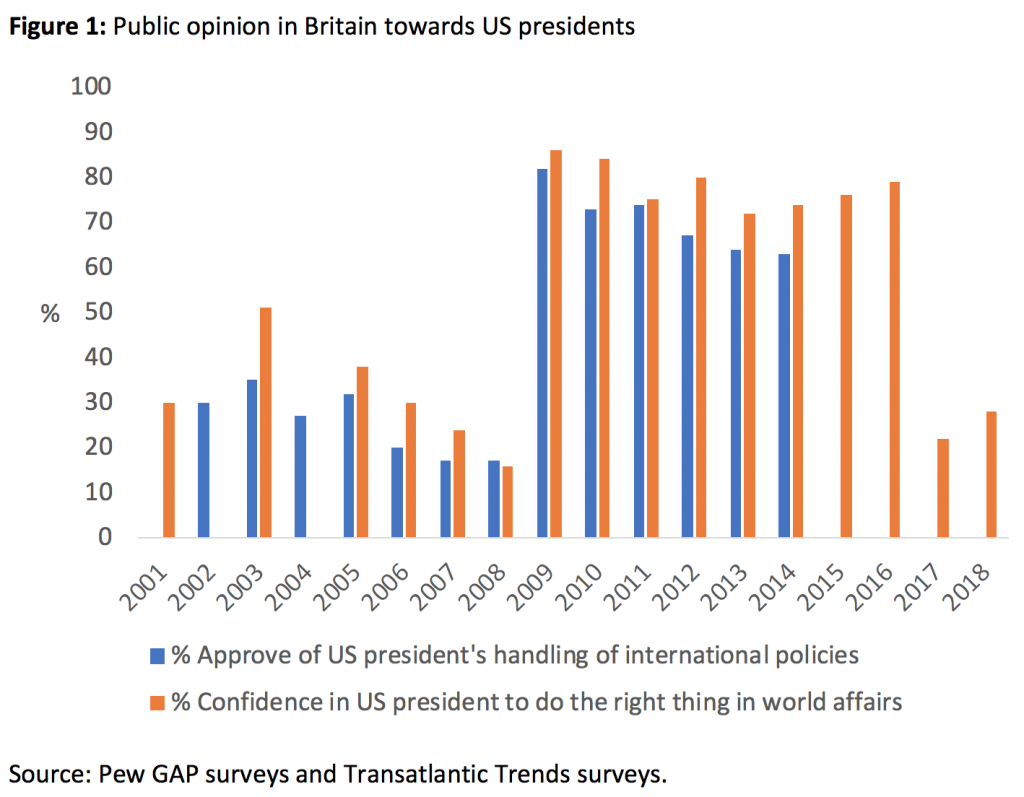

Cross-national survey series – the Pew Global Attitudes Project (GAP) and Transatlantic Trends (TT) – provide valuable data on this topic for the Britain public. Figure 1 shows the proportions of the British public (or UK public for the TT surveys) with positive evaluations of recent US presidents, specifically their role in international affairs. During the Bush presidency, public confidence was very low (highest in 2003 and falling away thereafter). The Obama bounce seen from 2008 to 2009 is striking: levels of confidence in 2008 and 2009 were, respectively, 16% and 86%. The data from the TT surveys only run to 2014 but similarly show the stark difference in public evaluations of Bush and Obama during their respective periods in office (17% expressed confidence in 2008, which shot up to 82% in 2009).

In the 2017 Pew GAP survey, coinciding with the start of Trump’s presidency, confidence levels in Britain fell dramatically to 22% from 79% in 2016, but increased a bit, to 28%, in 2018. In the early years of his presidency, Trump has been as deeply unpopular with the British public as Bush was at the end of his time in office. Gallup polling of public views towards world leaders similarly confirms the public’s negative views of Trump – in 2018, of those polled in the UK, just 26% approved of his leadership compared to 64% who disapproved.

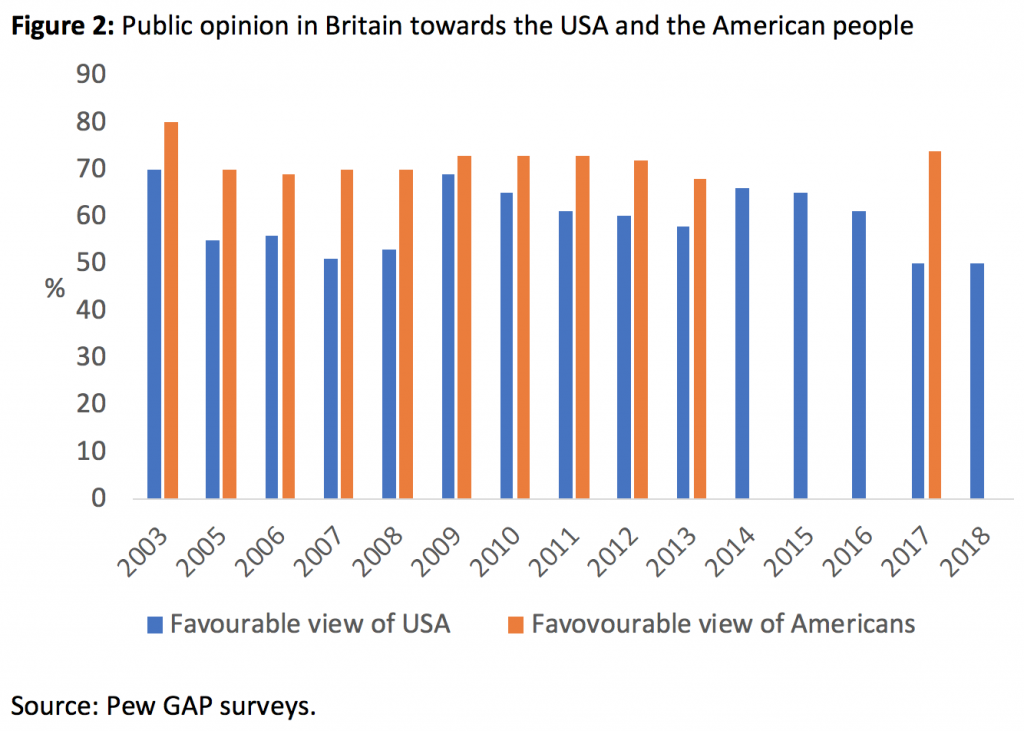

Figure 2 shows the proportions of the British public with favourable evaluations of (i) the USA and (ii) the American people, based on data from the Pew GAP surveys. It is immediately clear that the British public has tended, on balance, to hold favourable views of the USA and the American public, with the latter tending to run at higher levels than the former. These views have not seen the significant shifts which have accompanied changes in the US president. But in the years bookending the changes in the presidency, there has been some clear movement in levels of support for the USA (rising from 53% in 2008 to 69% in 2009; falling from 61% in 2016 to 50% in 2017), while affection for the American people has held relatively steady. In reverse transatlantic perspective, Gallup data show that the US public has held predominately favourable and broadly unchanging views towards Britain over the last three decades.

The evidence from the Pew GAP surveys tends to confirm the more positive views of the American people (and to a lesser extent, the US as a country), which tend to endure over time. In contrast, the public mood can – at different times – be particularly warm or cold towards different presidents, as clearly evident in the sharply changing sentiment towards Bush, Obama and Trump. In the aggregate, British public opinion has been largely unfavourable to Trump’s presidency so far; but have some societal groups been more supportive – or, rather, less critical – of the Trump administration and its policies?

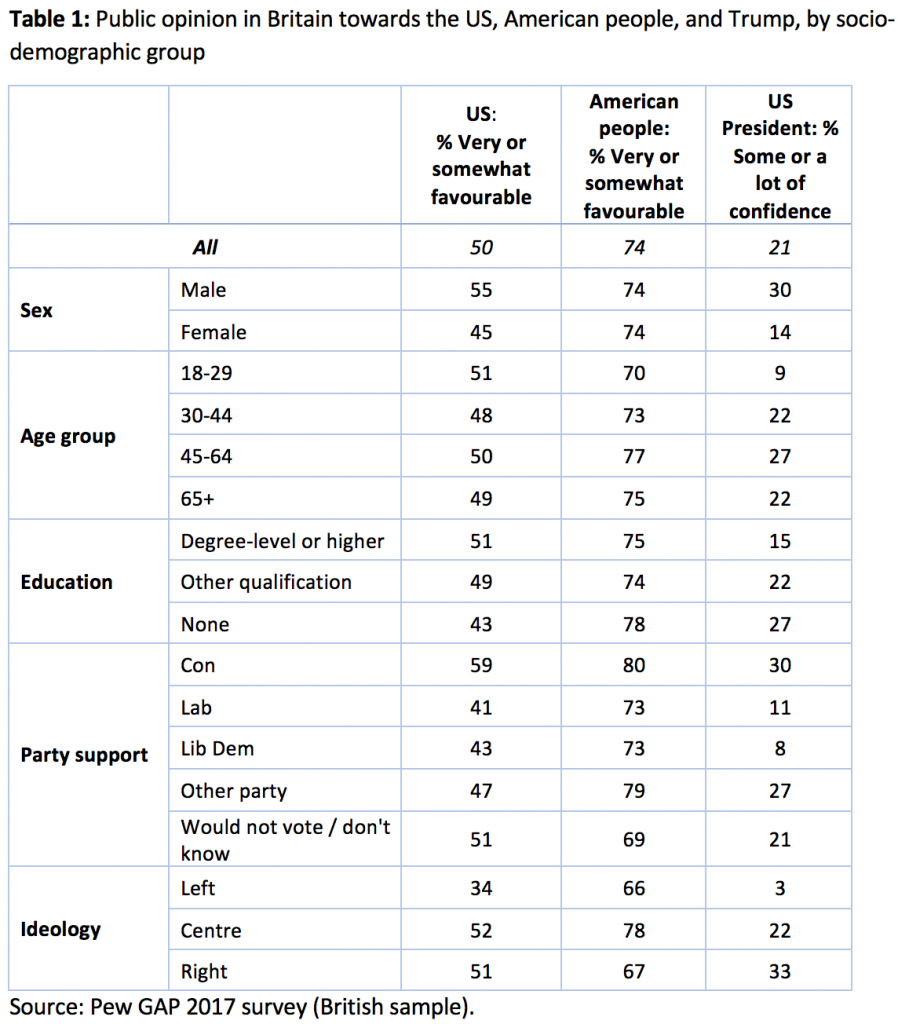

Further analysis of the Pew 2017 GAP survey (the most recent available for secondary analysis) sheds light on this question. For a range of socio-demographic groups in British society, Table 1 compares the proportions with favourable views of the (i) the US (overall: 50%), (ii) the American people (74%) and (iii) President Trump (21%). Focusing on views towards Trump, while levels of confidence are low or very low across all socio-demographic groups, there is some variation: expressions of confidence were lowest amongst women, those aged 18-29, those with a degree or higher-level qualification, Labour and Lib Dem supporters, and those on the ideological left. All socio-demographic groups were much warmer in their views of the American people (consistently registering strong majorities) than towards the USA as a country.

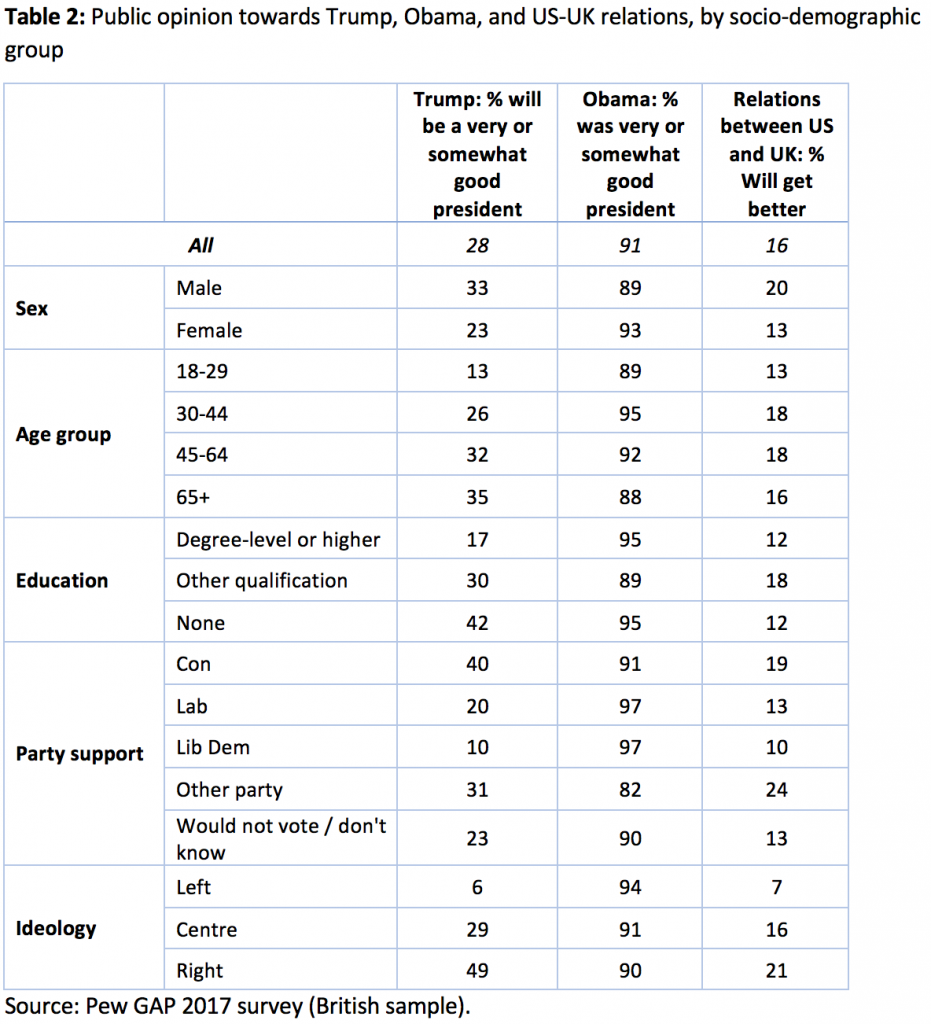

Table 2, again based on data from the Pew Gap 2017 survey, reports evaluations of whether Trump will prove to be a good president or not, appraisals of Obama’s presidency, and whether US-UK relations will improve. Overall, in 2017, just 28% of the British public expected that Trump would be a somewhat or very good president and only 16% expected relations between the two countries to improve. In distinct contrast, 91% had a positive view, in retrospect, about Obama’s presidency. For both questions about Trump, the most negative appraisals were found amongst those on the ideological left. Retrospective assessments of Obama’s presidency were overwhelmingly positive across all socio-demographic groups, with little variation based on party-political preference or ideological location.

The British public has also expressed strong opposition to some of the Trump administration’s signature policies that have exemplified the ‘America First’ agenda overseas. Overall, Table 3 shows a majority of the British public disapproving of each policy, when asked in the Pew Gap 2017 survey. Table 3 also shows the proportion, within each sociodemographic group, that disapproved of each policy. As was seen for evaluations of Trump as president, there is some evidence of variation in opinion across groups within wider society. In relation to placing more restrictions on those entering the US from some majority-Muslim countries, for example, there is relatively less disapproval amongst men, older people, those with lower level or no qualifications, Conservative supporters, and those on ideological right.

In recent years, the British public have consistently expressed high levels of positive sentiment towards the American people, have been reasonably well-disposed towards the US as a country, but have shown marked fluctuations in their assessments of recent presidents. In terms of the current incumbent of the White House, the British public have, on the whole, been markedly negative in their appraisal of Trump’s presidency and policies in the international context.

___________________

Ben Clements is Associate Professor in the School of History, Politics and International Relations at the University of Leicester. The above draws upon research from his latest book, British Public Opinion on Foreign and Defence Policy: 1945-2017 (2018, Routledge).

Ben Clements is Associate Professor in the School of History, Politics and International Relations at the University of Leicester. The above draws upon research from his latest book, British Public Opinion on Foreign and Defence Policy: 1945-2017 (2018, Routledge).

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Featured image credit: Pixabay (Public Domain).