Alia Middleton uses evidence from the last four general elections to explain the logic of party leaders’ campaign strategies.

Alia Middleton uses evidence from the last four general elections to explain the logic of party leaders’ campaign strategies.

There are sure-fire ways to know that an election campaign has started in the UK, including that battle buses are unveiled and party leaders begin to make their way around the country. From Boris Johnson bursting through a wall on a digger to Jeremy Corbyn making hot chocolate reindeer with schoolchildren, these visits not only form an important way in which a leader and their party are projected, but they also give us important cues about party ambition. There is also some evidence that they can affect voter behaviour.

The campaign trail, or the series of visits made during election campaigns, has been extensively studied in the US, but such studies are comparatively rare in the UK. While there are important similarities in understanding motivations for visiting particular areas of the country, key dimensions of the US context do not easily apply to the UK. I have been studying the campaign trail and collecting data on leader visits since 2010, and the publication of my book Communicating and Strategising Leaders in British Elections is an in-depth, dedicated examination of where Conservative, Labour, and Liberal Democrat leaders went and why.

Key visit considerations

It is of course not feasible for a party leader to visit every single constituency over the course of an election campaign – between 2010 and 2019, the average campaign period has been 34 days, which would equate to visiting 18 constituencies per day. Party finances may pose further restrictions. Therefore, the campaign trail is heavily strategised.

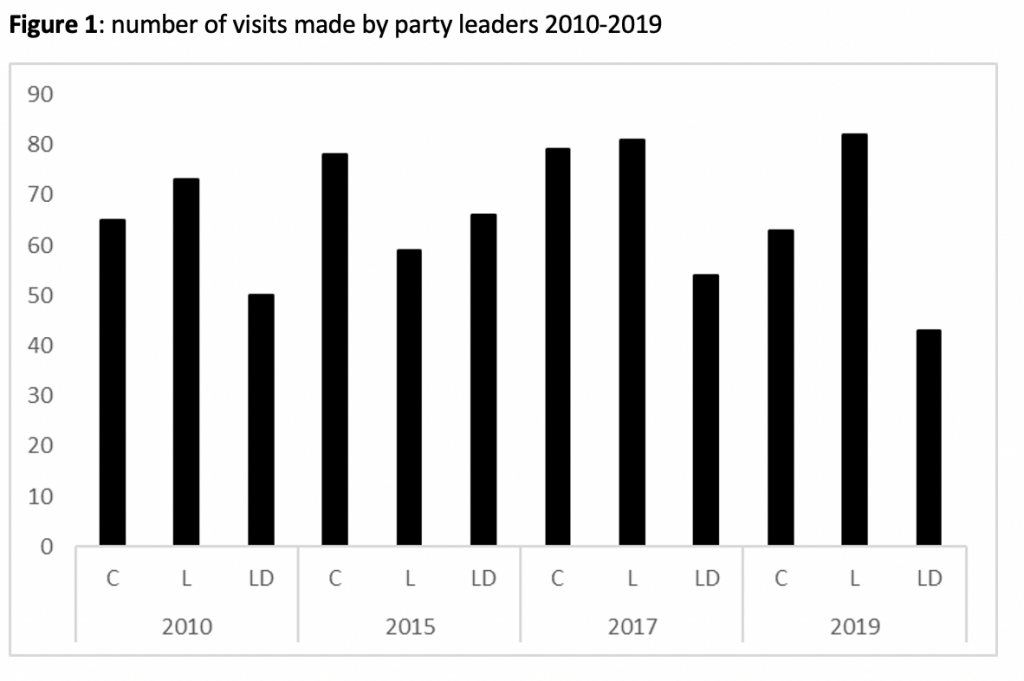

As Figure 1 shows, the number of visits that leaders make during election campaigns ranges, and days where leaders make a flurry of consecutive visits are common.

Delving into the constituencies visited by party leaders, at first it may look that they visit mainly marginal seats – the average majority of their party’s vote was lower in areas they visited compared to areas they did not. But the true picture is far more complex. With the 2017 election having been called to help strengthen Theresa May’s hand at the Brexit negotiating table, and the 2019 Conservative campaign having been centred around the slogan ‘Get Brexit Done’, Brexit voting patterns were also key in determining where leaders visited in these campaigns.

Theresa May operated a marginally pro-Brexit strategy, with the average Leave vote in seats she visited having been 51%. Moreover, many of the most Leave-voting constituencies that she visited were northern seats with a history of Labour representation. Little difference could be seen between Corbyn and May’s visit patterns, although the average Leave vote in seats visited by Labour was marginally lower. The greatest contrast could be seen when looking at the Liberal Democrats. In 2017, Tim Farron visited seats with an average Leave vote more than ten points lower than both the Conservatives and Labour.

Brexit-based visit differences in the campaign trails were also observed more distinctly in 2019. Almost 70% of Johnson’s visits were to seats where the majority of the voting population had voted for Brexit. In contrast, Jo Swinson had clearly adopted a pro-Remain strategy, with the average Leave vote in seats she visited at 36%. Corbyn’s visits in 2019, on the other hand, remained fairly neutral, with an average vote share for Leave close to 50%.

Categories of visits

While in the US efforts have been made to categorise the campaign trail into fundraisers, rallies, and virtual events, these categories do not apply readily to the UK. Instead, visits by UK party leaders can be divided into inward-facing and outward-facing ones.

In outward-facing visits, the primary intended audience is national. They include grand-standing visits – such as large-scale speeches and manifesto launches – which typically take place in large events venues and in which party leaders articulate the ceremonials of political power, show off their statecraft abilities, and project authority. The second type of outward-facing visits are policy-oriented, where a leader’s appearance in a constituency takes place in a location relating to business, healthcare, education and so on. The leader will typically be taken on a tour of a workplace, perhaps give a speech to workers or engage in newsworthy photo opportunities.

There are similarly two categories of inward-facing visits, where the primary intended audience is local. The first are cheerleading visits, which typically include speeches given indoors and out to local party activists accompanied by some judicious placard-waving. These are less formal than grand-standing visits. The second category are campaigning visits and include activities such as canvassing with the local candidate or conducting walkabouts in the constituency. The unstructured potential of these visits can result in unplanned, unrestricted encounters with members of the public; this type of visit is potentially the most risky and most usually associated with campaign trail difficulties.

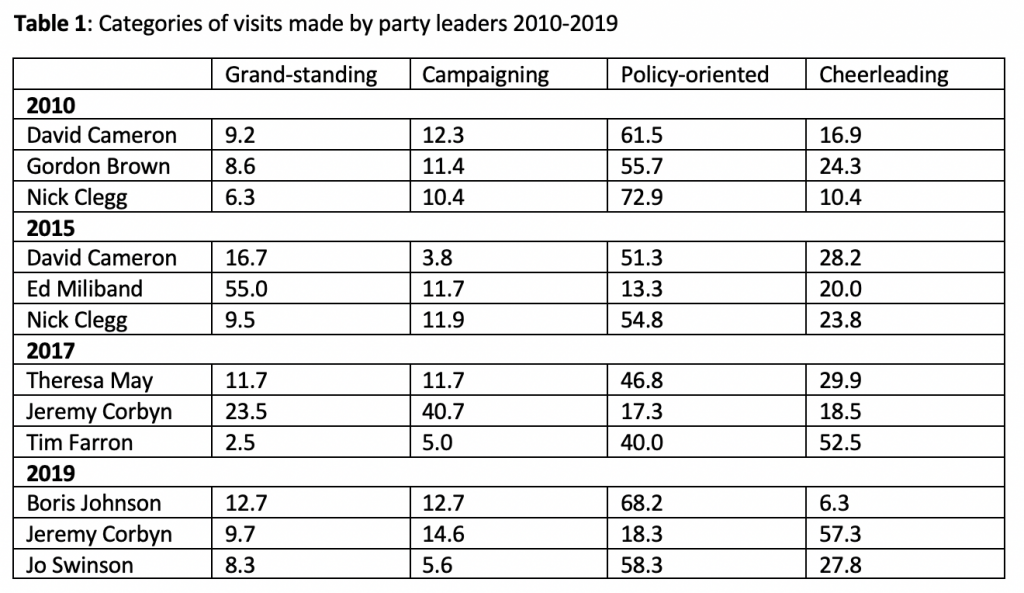

As seen in Table 1, the types of visits that leaders made fluctuated between elections and between leaders. Breaking the categories down by marginality, grand-standing visits took place in ultra-safe seats, whereas policy visits and cheerleading visits took place in more marginal seats.

While policy-themed visits were the most common type of visit for all three party leaders in 2010, there have been some considerable shifts in the three elections since. Ed Miliband in 2015, keen to project himself as capable of handling the reins of power, used his visits as grand-standing opportunities. In 2017, Jeremy Corbyn articulated himself as a leader/campaigner, evinced by the frequent large-scale, open-air public speeches he gave. However, his campaign in 2019 become more focused on enthusing local activists. While policy-themed visits remained the most frequent type of visit for the Liberal Democrat leaders, there was a not-inconsiderable concentration of cheerleading visits where the leaders engaged with their traditionally strong local party organisations.

The campaign trail is a carefully planned series of public appearances in strategically selected locations. Backdrops are not coincidental: they are planned with particular messages in mind and particular audiences to connect with. It is worth bearing this in mind the next time you see a battle bus pull up.

___________________

Alia Middleton is Lecturer in Politics at the University of Surrey.

Alia Middleton is Lecturer in Politics at the University of Surrey.

Photo by david laws on Unsplash.