Many think that the UK’s crisis is the result of a series of mistakes individual prime ministers made: Boris Johnson, Theresa May, Liz Truss. But a deeper look reveals the source of these mistakes: the ideology of rampant individualism that has taken over our politics and economics since Thatcher, argues Will Hutton. Keir Starmer has the opportunity to put an end to this era of mistakes.

Crisis is an over-used word, but Britain’s interdependent economic, social and political ills surely merits the term. Almost every dial on the economic and social dashboard is flashing red, and there is little confidence that our degraded political system is capable of mounting the necessary response. The twin resignations of Liz Truss and Boris Johnson two years ago were both emblematic of the crisis – and a tribute to is profundity.

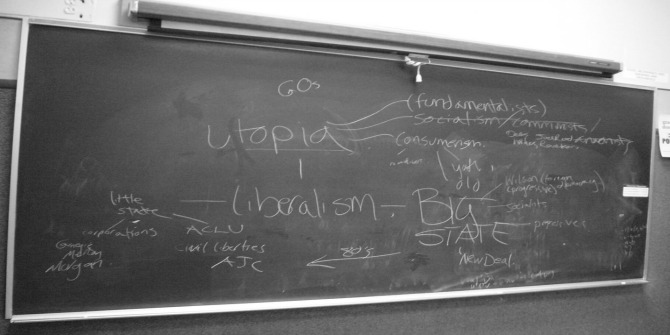

Behind the chronically poor figures for public and private investment, the desperately slow growth of already low productivity and the scale of dismaying social need, lies a value system that places the individualist “I” at the centre of the moral, economic and social universe. Markets driven by individual consumers and individual businesses, have argued its proponents since Margaret Thatcher, will self-organise to produce the best outcomes – morally, economically and socially. This in turn requires constant efforts to keep the state small so as to enlarge the scope for individual action.

This was the thinking behind Thatcher’s monetarism and financial Big Bang, and followed by austerity, Brexit and Liz Truss’s damning 49-day Prime Ministership. They were all first order mistakes. A country can survive one, perhaps two – but not five.

An emphasis on the “We” is not some justification for “socialism” coming out of left field: it is an inherent part of the human condition.

It is time for more pro-social policies that assert the “We” to build a capitalism that accepts a societal obligation hard-wired into its DNA and its necessary dependence on a strong society. It was Aristotle who wrote that “anyone who cannot lead the common life, or is so self-sufficient and does not want to partake of society is either a beast or a god”. John Donne, perhaps our greatest poet, wrote that “No man is an island, entire of itself. Each is a piece of the continent – a part of the main”. An emphasis on the “We” is not some justification for “socialism” coming out of left field: it is an inherent part of the human condition.

Capitalism has to partake of society, and accept the guiderails, superintendence and proactive management that are an imperative if it is to work for the common good – an imperative largely ignored since Mrs Thatcher’s election in 1979. As a result, it has an ineluctable tendency to become either a fallen god or an untamed beast. If capitalism’s capacity for innovation and change is to be harnessed for the common good, these failings have to be addressed.

My book This Time No Mistakes calls for a marriage of ethical socialism to undergird the “We” and a progressive liberalism to reframe the “ I” , tempering individual ambition with a sense of obligation to the whole. The “We Society” for which I argue recognises both the need for a social floor and individual ambition and agency to climb up whatever ladder, but within a stakeholder capitalism that seeks to make profits from pursuing great social purposes. It is not an impossible ask – nor so difficult to deliver. Or at least it shouldn’t be.

I thought when I finished writing the book that the ideas and policies might be too ambitious for Starmer’s Labour party

The best reforming governments – the Liberals between 1906 and 1914 and Labour between 1945 and 51 – have managed this alchemy in the circumstances of the time. The task in 2024 is to do the same again. I thought when I finished writing the book that the ideas and policies might be too ambitious for Starmer’s Labour party. I want to lift the economy by decisively raising public investment, reshaping our savings and investment ecosystem so it dramatically raises its support for business and to reconfigure our capitalism around the delivery of great purposes rather than putting profit first. Our tech sector needs careful nourishing rather than to be sold off abroad. Workforces need to be enfranchised. All these are measures to insert more “We” into the economy to create ladders up.

If Starmer meant what he said, Labour may be more of a reforming government than most expect.

Socially we must invest in our society – housing, criminal justice, public health, income support, nutrition, the arts, education and training. And politically our constitution and governance system needs an overhaul from top to bottom.

Keir Starmer volunteered to come to one of the opening events to launch the book, telling an audience of more than 500 that the book was “brilliant”, urged everyone to read it and positioned Labour as being in synch with the drive of the argument. If Starmer meant what he said, Labour may be more of a reforming government than most expect. Perhaps this time there will be no mistakes.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Image credit: Martin Suker on Shutterstock