Prime Minister Rishi Sunak has made it his mission to “stop the boats” crossing the Channel. Yet such slogans ignore the humanity and individuality of those arriving on the shores of the UK and provides no insight into the complex factors and circumstances underlying people’s decision to attempt the crossing. Woodren Brade uncovers the reality behind the rhetoric.

In February, the Home Office updated their statistics on all aspects of the immigration data. This data allows us to unpack and analyse the truth about Channel crossings, to present the accurate picture of who these people are, and why they are being forced to take this treacherous journey.

During 2022, 45,755 men, women and children crossed the Channel in a small boat to reach the UK. In contrast to the government repeatedly calling these people “illegal”, our analysis has found that two thirds (27,000) of all those who made the crossing would be recognised as refugees if the government processed their asylum applications.

Of all those who crossed in small boats in 2022, 16 per cent were children. We know from our extensive work with child refugees that these 7,177 children who arrive alone, or as part of family groups, are very likely to be traumatised, having undergone a dangerous and gruelling journey. These children are often then met with suspicion, where their age is immediately disputed, frequently ending up in highly unsuitable and unsafe accommodation.

| 2022 | Recorded Channel Crossings |

Percentage of all Channel crossings in 2022 |

Asylum grant rates at initial decision (main applicants) |

Resettled | Family Reunion |

| Afghanistan | 8633 | 20% | 98% | 72 | 141 |

| Iran | 5642 | 13% | 80% | 10 | 667 |

| Syria | 2916 | 7% | 98% | 569 | 924 |

| Eritrea | 1,942 | 5% | 98% | 19 | 554 |

| Sudan | 1704 | 4% | 84% | 218 | 572 |

| Total | 20837 | 48% | 888 | 2858 |

Source: Refugee Council analysis of Home Office statistics year ending December 2022, Irregular Migration to the UK data tables

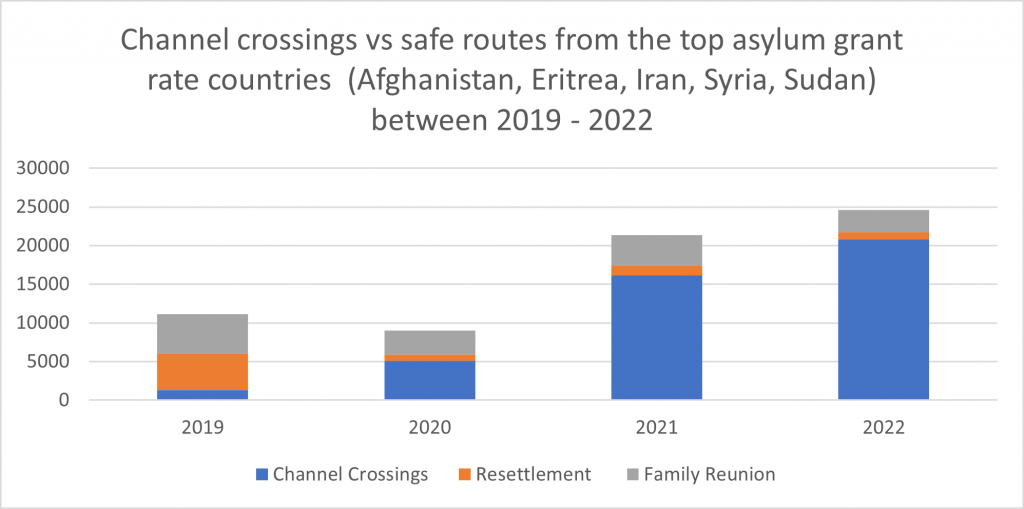

Nearly half (48 per cent) of those who crossed the Channel in 2022 came from just five countries – Afghanistan, Iran, Syria, Eritrea and Sudan. Three of those nationalities currently have asylum grant rates of 98 per cent and the other two are 84 per cent and 80 per cent. The rise in Channel crossings from 2019 to 2022 made by this group has been dramatic. In particular, Channel crossings by Afghan nationals have consistently increased every year since 2019, rising from just 69 to 8,633 in 2022 – about 125 times higher and making up 20 per cent of all Channel crossings in 2022. The increase in Afghan refugees crossing the Channel over 2021 and 2022 correlates with the Taliban takeover of Afghanistan in August 2021.

Channel crossings vs safe and legal routes

Refugee Council’s analysis has found that despite the very high asylum grant rate reflecting the danger that these refugees face in their home country, access to safe and legal routes to the UK has not followed suit. Overall, with the exception of Ukrainians, there are far fewer refugees arriving through safe routes than prior to the Covid-19 pandemic. Resettlement numbers are 75 per cent lower than in 2019 and the number of family reunion visas issued is 40 per cent below the pre-pandemic level. In 2022, the percentage of people from the top five high asylum grant rate countries that were crossing the Channel was 85 per cent versus 15 per cent arriving via safe and legal routes. This shows that the system of safe and legal routes is broken. The most prominent of all is the failure of the Afghan resettlement schemes promised by the government.

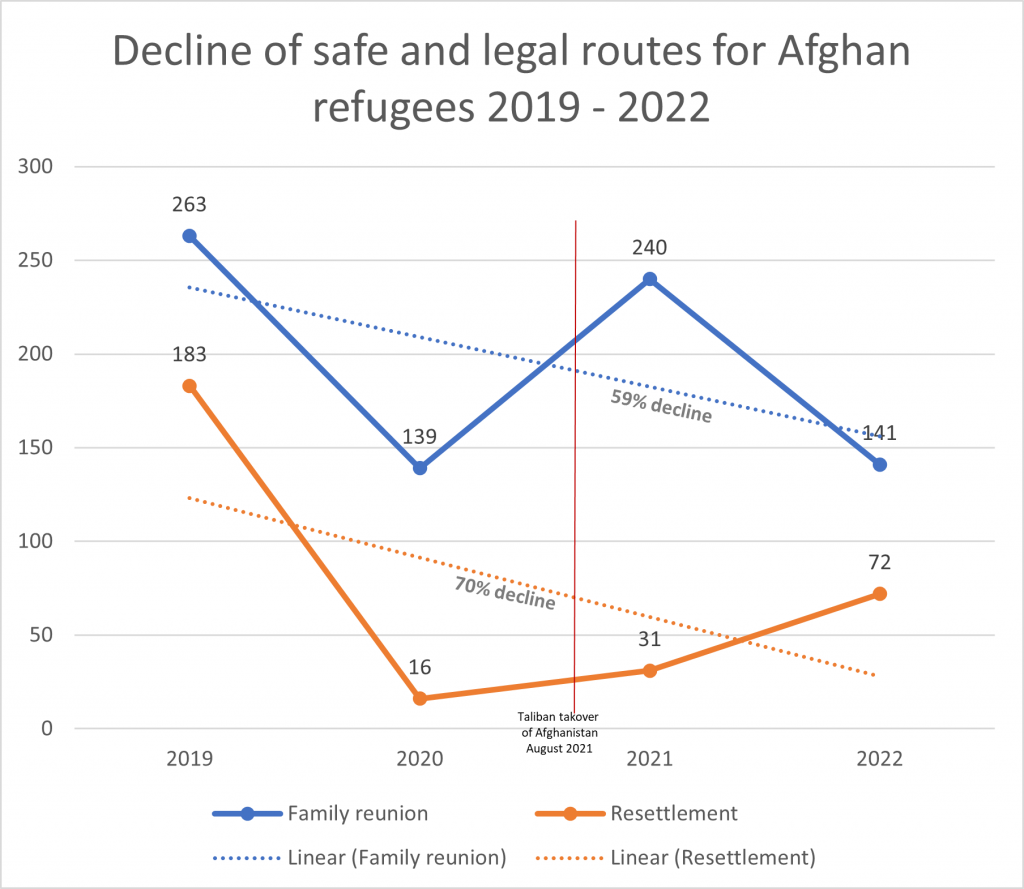

In January 2022 the Government formally opened the Afghan Citizens Resettlement Scheme (ACRS), vowing to resettle 5,000 Afghan refugees in the first year and 20,000 over the coming years. Despite these promises, in 2022 only 22 Afghans have been resettled in the UK on ACRS and 72 Afghans overall, with only 141 Family Reunions made. Accessible safe and legal routes for Afghan refugees have significantly declined since the Taliban takeover of Afghanistan in August 2021, despite the UK government’s promises to ensure thousands would be resettled in the first year. Between 2019 and 2022, resettlement for Afghans has declined by 61 per cent and family reunion by 46 per cent. Similar trends are observed for other nationalities: resettlement has declined by 87 per cent for Syrians and 75 per cent for Eritreans, while family reunion has declined by 65 per cent for Eritreans, 66 per cent for Iranians and 48 per cent for Sudanese.

This dramatic rise in Channel crossings versus the steep decline in safe and legal routes demonstrates that, despite the government’s promises, refugees who make the dangerous journey and are exploited by ruthless people smugglers have no choice – they do not have access to safe routes to reach the UK despite serious ongoing conflict, danger and displacement in their home countries.

Misleading rhetoric

Statistics show that the majority of people crossing the Channel would be recognised as refugees if the UK government processed their asylum applications. This contrasts with the message that is being communicated by the government and some of the more extreme language politicians have chosen to use. Rishi Sunak has repeatedly and incorrectly referred to people in small boats as “illegal”, while Home Secretary Suella Braverman went further and described their arrivals as an “invasion”.

Statistics show that the majority of people crossing the Channel would be recognised as refugees if the UK government processed their asylum applications.

It is clear, however, that the issues the government raises, like the crisis of hotel asylum accommodation, are not a result of the increase in Channel crossings but rather the inescapable consequence of the asylum backlog which has hit a record high, with over 160,000 people waiting for an initial decision on their asylum claim. This is over triple the number it was at the end of 2019. Recent commitments to deal with the backlog are welcome, but a new process outlined as part of this commitment is unworkable and discriminatory. This distorted and misleading picture created by the government and some in the media can stir tension and creates a context where extremists use a build-up of far-right hate to create further hostility towards people seeking asylum crossing the Channel.

An unworkable and futile response

The Government has just announced a new Asylum Bill with the stated intention of stopping people crossing the Channel in small boats. The Bill seeks to prohibit anyone who has travelled through another “safe country” and arrived irregularly (including crossing the Channel) from gaining protection in the UK. Asylum claims from such people will be deemed inadmissible, and they will most likely be detained pending their removal to either their country of origin or a “safe” third country. However, there have been no details on where exactly the government intends to send at least 45,000 people (with the inhumane Rwanda scheme not even off the ground due to legal and practical challenges).

The Bill also fails to establish new safe and legal routes and places a cap on existing ones, which are already limited and often subject to lengthy delays. If this Bill comes into force, it will leave all those who cross over on small boats stuck in limbo and potentially facing long periods locked up in detention. Furthermore, the government won’t be able to remove the many thousands who are expected to come from places like Afghanistan, Syria and Iran – high grant-rate countries that people clearly can’t be returned to. Yet the Bill won’t process their claims either, leaving them in extremely precarious and vulnerable situations, at risk of destitution and homelessness.

The truth

The truth about Channel crossings is that the majority of people risking their lives in small boats would be granted asylum if the government processed their asylum claim. The reality of who these people are is far from how the government is trying to depict them. This risks creating a space where misconceptions within the public can, in extreme circumstances, result in serious acts of violence and hostility towards people who are extremely vulnerable and have fled from deeply traumatic situations. The dramatic rise in Channel crossings is a direct result of the scarcity and steep decline of safe routes. Until the government takes meaningful steps to increase access to safe and legal routes, it will not be able to prevent desperate men, women and children making the treacherous journey across our Channel.

This post draws on analysis published by the Refugee Council.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Image credit: Number 10, Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)