Jack Shaw explains why the next Prime Minister must rethink the government’s strategy to boost civic pride – a core commitment of the otherwise vague ‘levelling up’ agenda.

Jack Shaw explains why the next Prime Minister must rethink the government’s strategy to boost civic pride – a core commitment of the otherwise vague ‘levelling up’ agenda.

As part of its mission to reduce the deep spatial divides that exist across the country, the emphasis the government’s Levelling Up White Paper places on boosting ‘pride in place’ is welcome. Boris Johnson described the progress of ‘levelling up’ as ‘when we have begun to raise living standards, spread opportunity, improved our public services and restored people’s sense of pride in their community’. Though it has featured on the periphery, Rishi Sunak also spoke warmly about the importance of civic pride in his leadership bid. It’s clear that government is only taking the first steps to charting a course to boost pride, but it would be wrong now to turn the ship around under a new Prime Minister.

The Bennett Institute’s new Townscapes: Pride in Place report explores a series of fundamental but complex and largely ignored questions related to civic pride: what constitutes it, what levers are available to boost it, and who ‘owns’ it. The rise of the ‘places that don’t matter’ has added urgency to such questions, which are by no means unique to the United Kingdom, and these need to be answered regardless of who holds the keys to Downing Street.

Pride is, we suggest, worth pursuing. Yet the interest in pride in place has not been met with universal appeal. The charge-sheet against it is that boosting local forms of pride involves short-term, ‘hanging-basket’ style interventions which do little to improve the economic fortunes of places, particularly those that have been ‘left-behind’. Instead, with few exceptions, the focus in policy circles has been on the economic geography of left-behind places rather than the ‘emotional geography’ of such places.

The White Paper provides a partial corrective to this, but the progress Whitehall has made in sketching out the contours of feelings of pride in place has been limited. The White Paper identifies regeneration, communities and culture, heritage and sport as warranting attention in this respect, and on the surface these appear to be sensible. But on inspection, the government’s understanding of pride is, at best, incomplete. Plans to measure policies which have tangential relationships with feelings of pride in place – such as homeownership and homicide rates – suggest that Whitehall runs the risk of pursuing policies that will have little import.

It is difficult to draw a neat causal story, but the relationship between pride and a range of indicators – such as social capital, trust, and participation – suggest that pride can help create positive conditions for economic growth. And there is evidence from both the UK and United States that when people feel a strong connection with their communities, they are more willing to invest in them and the services that make living there worthwhile.

The sources of pride are also popular in the polls. For many, pride is about reimagining their high streets, so that they consist of quality, independent retailers and aren’t blighted by vacant premises. It is improving the standard of the public realm, so that green spaces can host children without the fear that play areas have been vandalised. It is ensuring that our communities have access to sporting facilities, local heritage, pubs and libraries. Too many of these amenities have closed or fallen into disrepair in recent years.

But feelings of pride in place are more than the sum of physical infrastructure in a place: communities want to feel connected to the places that they live, and to possess a sense of ownership over and agency in those places. Change must happen ‘with’ them and not be done ‘to’ them. Looking to the past, communities want their histories celebrated – particularly industrial heritage – and looking to the future they want to see prospects for their children so that they can put down roots.

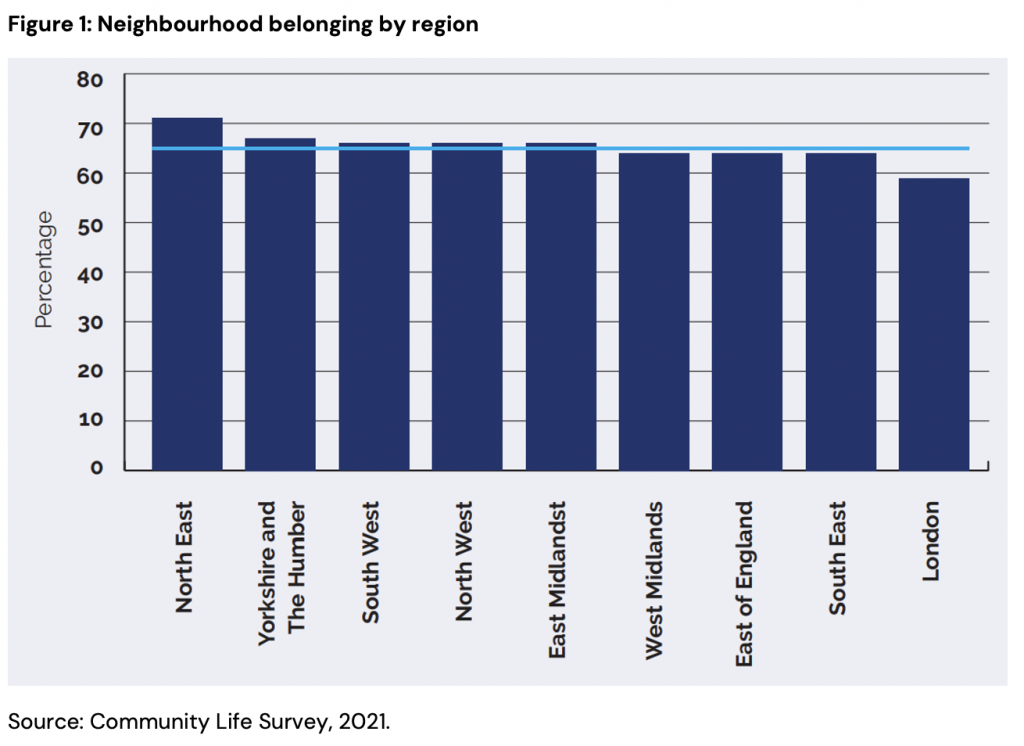

Too often, the assumption is made that, put simply, poor places have little pride. The idea that pride needs to be ‘restored’ in such places and has been in ‘decline’, as the White Paper sets out, is neither universal nor linear. There is a mixed record. For example, the North East – which records high levels of deprivation and disadvantage – records higher levels of belonging than London and the South East, as the image below demonstrates.

These phenomena are not too dissimilar to wellbeing where, according to the Office for National Statistics, there is no neat correlation between it and deprivation.

The scale of change required to boost pride has yet to be realised. For all the talk of ‘building’ and ‘boosting’, policymakers have been decidedly unambitious in their pursuit of pride. The axis policymakers should be thinking along goes beyond either short-term funding for cosmetic initiatives on high streets or a resolute focus on the economy at the expense of the culture and identity that binds communities. Instead, in recognising that feelings of pride in place are contingent and contextual, policymakers must seek to address the challenges facing communities across multiple dimensions.

That is why we are calling on the next Prime Minister to set out a ‘minimum standard guarantee’ to ensure that every community in the country has, at a minimum, access to basic services they need to sustain themselves. As part of this, we suggest that the £150 million Community Ownership Fund is increased to £1 billion to reflect the scale of the challenge. On a per capita basis, this is in line with the Community Revitalisation Fund in the United States. We also suggest government create a new Minister for Civic Pride to drive this agenda, so that the sources of pride (or interventions that undermine it) – from regeneration to heritage to green spaces – do not fall within the cracks of departmental siloes.

There is much that remains unanswered about how we boost feelings of pride in place in practice, over what timescale that pride exists, and the precise causal direction of its relationships with a spectrum of public goods, from social capital to trust. Despite misapprehensions about its value, it is clear that a renewed sense of local pride underpinned by quality and accessible public amenities, and rooted in a broad sense of community, history, and identity is an appealing platform that policymakers would do well to consider. Policymakers should steer clear of jettisoning pride in place – and the broader agenda that spawned it.

____________________

Jack Shaw is an Affiliated Researcher at the University of Cambridge’s Bennett Institute for Public Policy.

Jack Shaw is an Affiliated Researcher at the University of Cambridge’s Bennett Institute for Public Policy.

Photo by Nina Strehl on Unsplash.