Since their introduction by the Blair government in 2000, Academy schools have proved deeply controversial. Becky Francis reflects on the report of the Academies Commission, which investigated whether this educational innovation was meeting the goals for which they were originally intended. An emerging consensus suggests that autonomy for such schools must be married to collaboration and, at present, it has yet to be established whether this will come to be broadly true across the system.

Since their introduction by the Blair government in 2000, Academy schools have proved deeply controversial. Becky Francis reflects on the report of the Academies Commission, which investigated whether this educational innovation was meeting the goals for which they were originally intended. An emerging consensus suggests that autonomy for such schools must be married to collaboration and, at present, it has yet to be established whether this will come to be broadly true across the system.

How can we secure the school-to-school collaboration unanimously agreed to be so vital for school improvement, in a system of autonomous schools operating in competition with one another? This has emerged as a central question in the debates following the launch of the Academies Commission Report. The response to the Commission Report has been overwhelmingly positive and constructive: both supporters and detractors of the academies programme have welcomed the thorough and impartial analysis as long overdue. A Guardian editorial commended it as a ‘serious careful piece of work’ written by ‘critical friends’ of the academies programme; while the Times predicted that Gove would welcome its constructive recommendations to strengthen the academies programme.

Arguably, there was something for everybody in it – The Times’ Greg Hurst described the Report as being fought over like a ‘golden curates egg’, as all sides seized on aspects that support their position. Educationalists have certainly engaged with different elements, but points of strong consensus have formed around a) the need for greater rigour in the academies programme in the form of transparency and accountability; and b) the need to secure school-to-school collaboration across the system, ensuring that the best practice among schools/academies and chains are reflected across the board.

Having Andreas Schleicher at hand at the Report launch provided peer review from an international perspective. While he welcomed out ‘excellent report’ and supported its foci, he was clearly worried that our recommendations to encourage collaboration did not go far enough. He pointed out that, while more autonomous school systems are generally more successful than highly directed ones, there is a much stronger correlation between collaborative culture and system success. Indeed, he noted that the lowest performing schools in the OECD have autonomy but no collaborative culture. Shleicher reports that the world is watching the English academies programme, which is the first case whereby state-funded independent schools are expected to collaborate. If successful, the programme could provide an exemplary case. But he noted our finding that many converters are not honouring their commitments to support struggling local schools, and how ensuring collaboration is harder in competitive systems.

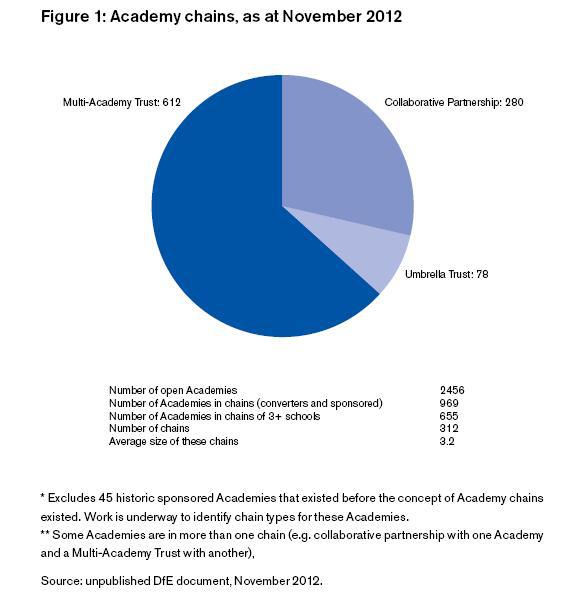

Chains and federations represent the most formalised expressions of collaboration – although as the Report details, such arrangements do not in themselves guarantee improvement. As we document in the report, at present there are 612 Multi-Academy Trusts, 280 Collaborative Partnerships and 78 Umbrella Trusts:

There are of course many exemplary cases of school-to-school collaboration and mutual support, among converter academies, academy chains, and elsewhere – and the Commission has been privileged to have heard from many. However, as we report, this was not true of all. We also heard from schools which felt they needed to target their energies at competition rather than collaboration, and that some converter Governing bodies see school-to-school support as a low priority. The danger is that, if incentives are not found to secure school-to-school collaboration, we will see brilliant practice in some areas and groups, while other schools continue in isolation. In these cases, risks of a lack of support for struggling schools, and potential complacency for isolated converters, is clear. The Commission recommends that converters be held to account for the commitments they made in application for conversion to support struggling schools, and that in future this be written in to their funding agreements.

Schleicher agreed, and also strongly welcomed the Academies Commission recommendation that Ofsted judge school leadership outstanding only if a contribution to system-wide improvement can be evidenced. However, he was clearly sceptical that this alone would be sufficient to lever the collaboration he – and the Commissioners – see as so vital for system improvement. And as he observed, the more autonomy schools have, the harder it becomes for the Government to intervene with them. These points have been made by several other key experts in response to the report. It seems imperative that the Government act speedily to implement our recommendations to secure the collaborative activity envisioned in the Schools White Paper, and scrutinise developments, to ensure the academies programme realises its promise of a better education for every child.

This was originally posted on the Pearson Think Tank blog

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

Becky Francis is Professor of Education and Social Justice at Kings College London. Best known for her work on gender and achievement, Becky’s research has focused on social identities in education and educational in/equalities